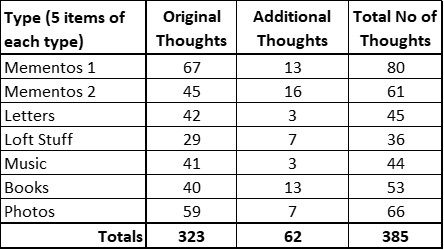

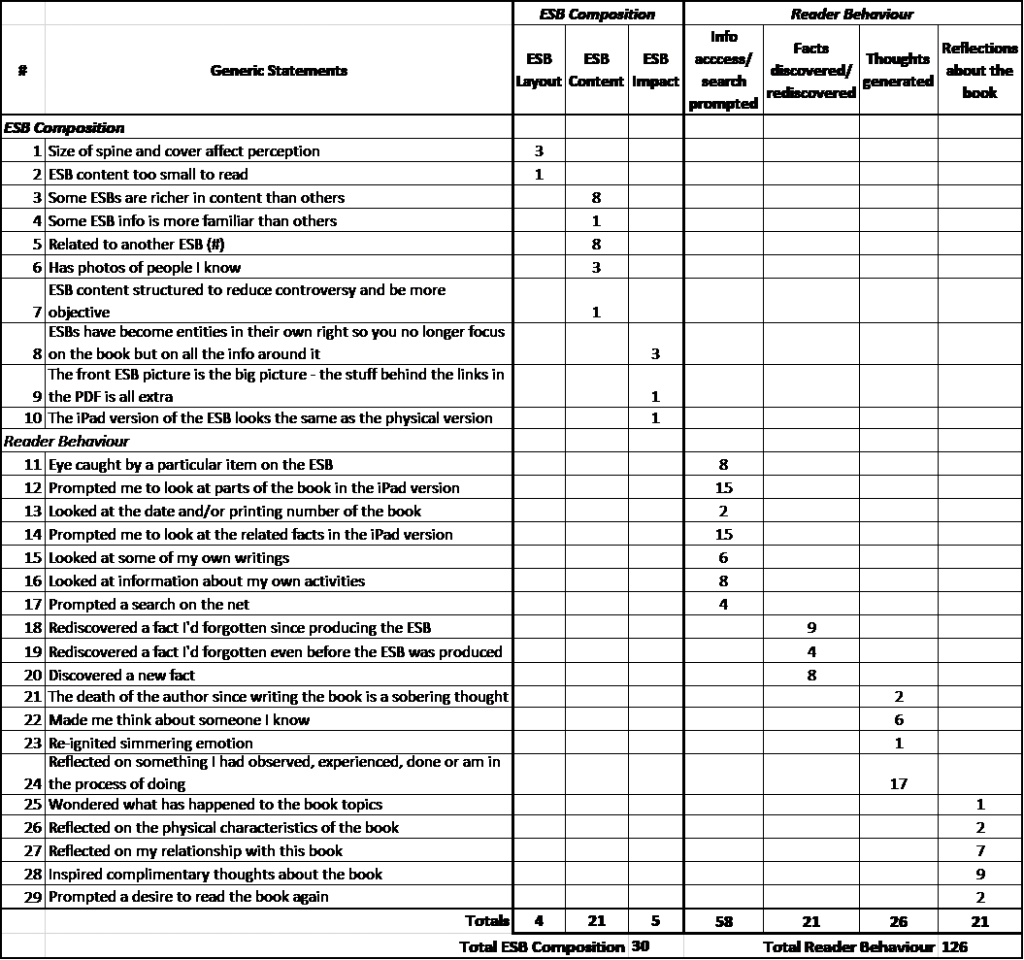

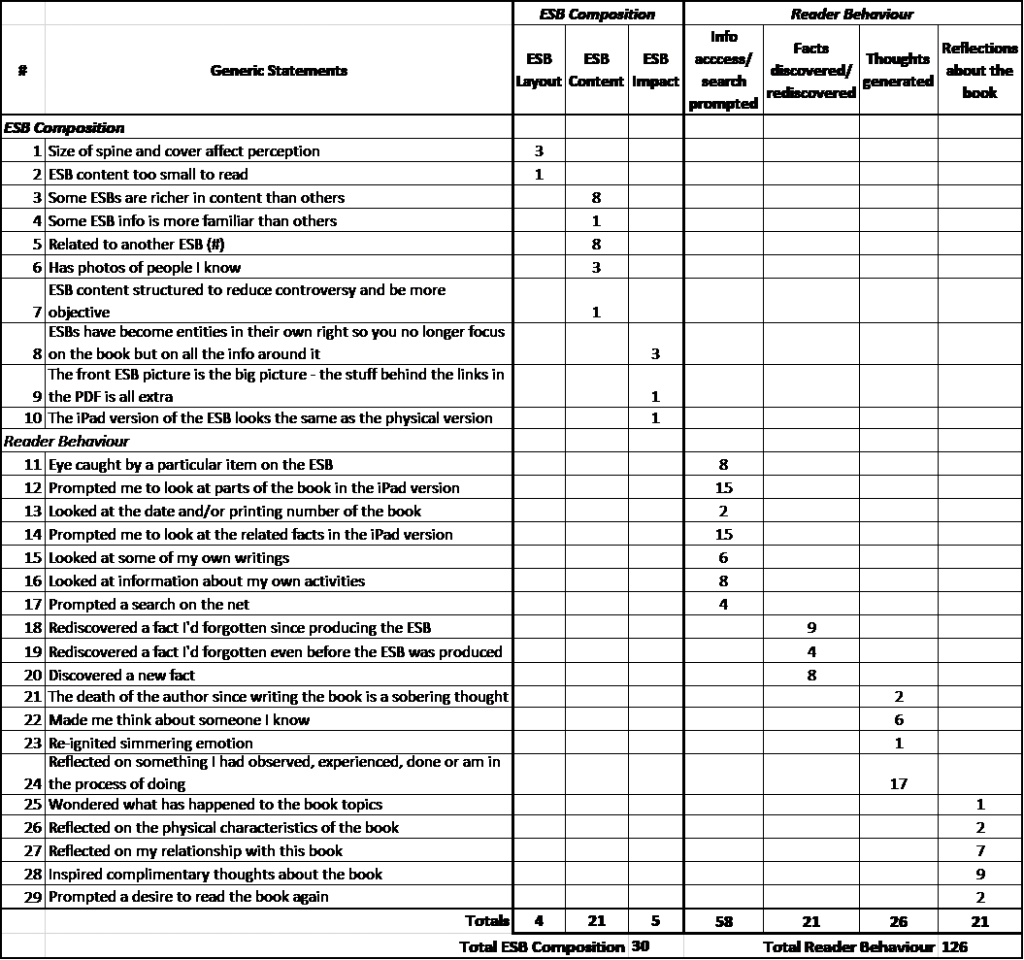

I’ve now been through all 34 ESBs and made notes of between 30 and 300 words on my interaction with each one. This entry analyses those notes and derives some implications for the design of ESBs. The analysis assessed each part of the notes text and identified specific actions or observations as an itemised list. After completing this exercise for all 34 books, the itemised lists were inspected and generic statements derived for each item. For example, specific item d) for Book No 17 was ‘Read press release of merger’, and from this the generic statement ‘Prompted me to look at the related facts in the iPad version’ was derived. The generic statements were gradually standardised as the analysis proceeded and during a subsequent refinement process. The standardised generic statements were then grouped into two main sets (ESB Composition, and Reader Behaviour) and placed into one of seven categories – Layout, Content, Impact, Information access/search prompted, Facts discovered/re-discovered, Thoughts generated, and Reflections about the book. The generic statements, and the number of books for which a particular statement occurred, are shown in the following table.

Observations relating to ESB composition

Observations relating to ESB composition

The observations relating to the design of the ESB fall into the following categories: Layout, Content, and Impact.

- Layout: All the ESBs were assembled using a standard template in which the book’s spine was placed in the centre of the page with the front cover immediately underneath it. Related points were placed around these two elements with those more intimately related to the book being closest to them. However, some of the spines and covers were smaller than others, and this clearly made a difference. In one case the spine was not recognisable, and in another it was mistaken for the wrong book. Another observation recorded that a cover was particularly noticeable. A related observation noted that some text on one of the related facts on an ESB was too small to read.

- Content: There were several remarks about the range of material on the ESBs such as ‘Lot in the ESB’, ‘very interesting ESB’, ‘ESB seems so complete’, and ‘the range of topics on this ESB is relatively narrow’. One observation pointed out that some information on the ESBs is more familiar than other information. In three instances the presence of photos was remarked upon in a positive way, for example ‘has photos of people I know’. A feature which was not explicitly remarked upon, but which was identified during the analysis process, was that there were four instances of two ESBs which were related in some way or other.

- Impact: Some remarks made it clear that some ESB’s distracted attention from the book and appeared to be texts in their right. For example, ‘With the ESBs you no longer focus on the book (which is what you do with a physical bookshelf) but on all the other info around it’, and ‘ESBs have become entities in their own right and the books are fading into the background’.

Observations relating to Reader Behaviour with ESBs

The observations relating to reader interaction behaviour with ESBs fall into following categories: Information access and search, Facts discovered/re-discovered, Thoughts generated, and Reflections about the book.

- Information Access and Search: Quite often, a particular element on the ESB seemed to catch the eye (8 specific instances were noted). For example, ‘Noted that Forbes in 2002 voted it one of 3 most important business books in the last 20 years’, and ‘Noted that though it is the 53rd edition it was still fetching £10 on eBay’. Following an initial look at the ESB, I typically sought additional information either by following the link to the book itself (15 instances noted), following the links to the related information (another 15 instances noted – not necessarily the same 15), and conducting a search on the net (four instances). It is striking that several of the cases in which additional information was sought, involved reading texts I had written (6 instances) or reading documents related to work I had done (8 instances).

- Facts Discovered/Re-discovered: In the course of seeking out additional information, I noted 13 instances in which I rediscovered information I’d forgotten – nine items I’d forgotten since producing the ESBs, and 4 items I’d forgotten a long time previously. For example, ‘The ESB confirmed I visited the Media Lab twice and with whom’, and ‘Noted that at least one was written while I was at NCC’. Furthermore, there were eight instances in which I discovered new facts from within the material that the ESBs were linked to, or from the searches I conducted on the net, for example, ‘Last page of the book refers to collaboration between NCC and CIMTECH which I’m not sure I heard about’, and ‘Read Bell’s Wikipedia entry and found he was involved in the design of the Vax computer which DEC gave us for Hicom’.

- Thoughts Generated: As one would expect, reading the ESBs and the linked material prompted a whole raft of thoughts. The majority of those noted were related to something I had observed, experienced, or done (17 instances). For example, ‘Reflected that NCC’s demise is a sad story – but not, of course for the commercial operation NCC Group’, and ‘reflected on how right the Future Shock predictions were’, and ‘Read the last page of the first chapter and thought that the Harry Potter books might have been a more pleasurable experience than the films – perhaps true for many books.’. In another case, the experiences generated a simmering emotion within me which were re-ignited on reading an ESB. Another set of thoughts were about people I was reminded of – six instances of these were noted.

- Reflections about the Books: The notes made on the ESBs included several reflections on the books themselves. Many of these (9 instances) were compliments about the books, for example, ‘Hardcopy was a nice design and had lots of useful info – summed up technology and capabilities of the time’, and ‘Was reminded that this is a great read’. A further two instances recorded a desire to re-read the books concerned again. There were seven observations about my relationship with the books, for example, ‘Realised I hadn’t looked at the contents of this book for a long time’, and ‘Book didn’t live up to my expectations’, and ‘Don’t think I ever read this book but watched the film’. In two cases I reflected on the physical characteristics of the book, for example, ‘Glad I kept hardcopy since tabbed books are hard to represent in scans’. Finally, for one of the ESBs, I wondered what had happened to the topics covered in the book.

Implications for ESB design

The amount of material to include on an ESB is totally dependent on the analysis of the owner’s thoughts about the book. Some books will stimulate the owner more than others. Consequently, some ESBs will inevitably contain more information than others, and be more interesting to the owner than others. However, the most significant finding from the observations about ESB composition is that the ESBs become entities in their own right, and that attention is drawn away from the books around which they are structured. Consequently, the fact that some of the book spines and covers were too small to recognise and read, becomes even more significant. No matter how much material is available to include on the ESB, the book spine and cover must be easily readable.

Two other points regarding ESB content emerged from this investigation: photos of people were highlighted a few times, so it seems worthwhile including such items where possible; and it was noted that some ESBs were related to each other. This latter point could be simply dealt with in the physical versions of the ESBs by adding a note such as ‘See also ESB #’. However, with a large electronic display it may be more useful to link directly to the related background information rather than to another main ESB – this aspect has yet to be explored.

Other than these two points, the general design of the ESB’s with the book spine and cover in the centre and other material around it, seems to work well. Of course, with a large electronic display, the constraints of an A4 page would not apply, but the principle of book in the centre with material around it would still apply. However, if the display first presented a bookshelf display of all the spines, from which a book was selected, the ESB would not need the spine and could just display the folded-out dust jacket or the front and back covers – this aspect too has yet to be explored.

Reader behaviour observations indicated that the links to extracts from the books and to related material, were well used and useful. The fact that net searches were made for additional information, and that new facts were identified in some cases, indicates that a facility to enable a reader to add additional material to a fully electronic ESB might be useful. Readers might also use such a facility to record some of the many thoughts which the observations in this investigation make clear are occurring throughout the interaction with a particular ESB.