Dealing with documents is an inevitable part of office work, so filing work practices are not unusual – everyone has them. It’s just that if you operate a Reference Number-based filing system, those work practices may be a little different. In particular, every document has to be digitised, recorded in the Index, and placed in a single store.

Getting digitised documents is very much easier than it used to be. To start with, most documents are created and distributed electronically, so the amount of hardcopy is much reduced; and scanners these days are much cheaper and faster – and available in most of today’s offices. So, even if you are away from base, it will usually be possible to digitise hardcopy.

Recording a document in the Index is relatively quick and simple to do, provided that the number of Index fields is kept to a minimum. Then it is just a matter of creating a folder for the newly created Index entry; renaming the file to include the Reference Number and a short descriptive title similar to that specified in the Index Title field; and moving the renamed file to the newly created folder.

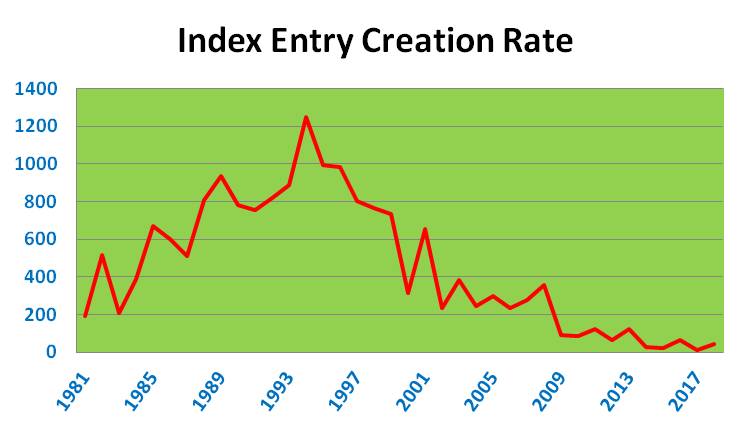

As with most regularly occurring activities, the less often you do it, the more the backlog builds up. I am firmly of the opinion that to operate this kind of filing system effectively, new documents should be put into the system as soon as they are received – or at least as soon as possible after that. However, whatever approach is taken, you will inevitably have to spend some time on the filing activity. If you want to reduce the time you spend, two possible strategies are, a) decide not to collect everything but only to collect documents on certain topics, or from certain people etc., so that the number of documents you need to file and manage is reduced; b) expand the scope of some index entries so that they will accommodate a greater number of documents, thereby reducing the number of new index entries and new folders that have to be created.

The benefit of having a digital filing collection is that, with today’s modern laptops and high capacity, cheap, storage, you can carry your information around with you and access it wherever and whenever you want. The commensurate downside of this is that your digital file store becomes a very precious commodity which needs to be protected and regularly backed-up in the event of loss or theft.

Specific questions relating to this aspect are answered below. Note that the status of each answer will fall into one of the following 5 categories: Not Started, Ideas Formed, Experience Gained, Partially Answered, Fully Answered.

Q36. How does this approach to filing affect work patterns?

2001 Answer: Experience gained: There are two main impacts. Firstly, it entails the regular indexing of new items as they are received and/or read. However, this not an absolute necessity since, as with any type of filing system, the new items can be piled up to be input in bulk sometime later. It is just much easier and effective to do a little often (Wilson 1990: 97). Secondly, it offers the opportunity to be much more sophisticated about capturing nuggets and developing knowledge. This almost certainly would affect work patterns, though it is not known how at present (Wilson 1997: 3 – 4).

2019 Answer: Fully answered: I am even more convinced than I was in 2001, that it is far better to include new items in the collection as soon as they are received and not to let documents accumulate. Scanning is no longer such a problem if you are away from your home base – a networked scanning capability can probably be found in most offices. If not, however, hardcopy documents have to be kept in a folder until you get back to your scanner.

It is probably best to keep a stock of the most recently acquired hardcopy (which you will already have digitised) in case you need them as working documents. This will entail having a designated box or drawer and managing it by eliminating the oldest when space becomes short. It is probably not worth recording in the index the existence of such a small specific stock of hardcopy.

Given that every item in the filing system will be digitised and stored on your laptop, it will be possible to carry around your entire collection and access it in any location. Such an accessible and useful store will inevitably become very precious, therefore you may need to take special measures to protect access in the case of loss or theft of the laptop; and you will need to maintain constant and effective backup arrangements.

Q37. What strategies can be employed to minimize user effort and maximize user motivation?

2001 Answer: Experience gained:

- Don’t attempt backfile conversion.

- File little and often, not lots infrequently.

- Minimize the number of fields to input when creating index entries.

2019 Answer: Fully answered: In addition to the strategies identified in 2001 (no backfile conversion, file little and often, and minimize the number of fields), I would add the following:

- Identify the categories of the documents you receive that you could do without and don’t file them.

- Expand the scope of your Reference Numbers so that you can put more files in those folders without having to create new index entries.

- Store just URL references for certain less important material so that you don’t have to copy text, create documents and save them to the digital store.

Note that the three strategies above involve making reductions in the overall set of documents that you file in the course of your work. This is dangerous because it’s difficult to predict which documents you will or won’t need to refer to in the long term. However, it’s a calculated risk based on your knowledge of what information you want and need to keep; and it may be a worthwhile risk if it reduces the filing load and gives you more motivation to keep abreast of the filing work.