One of the problems I’ve encountered many times is when photographing a painting or a poster or anything flat on the wall or placed on the floor: unless the camera is absolutely parallel with the flat surface in both the horizontal and vertical planes, the object looks distorted in the resulting photo. I’m not sure if it’s already been done, but a facility that made sure that such photos came out correctly would be a really useful feature on a camera (among the many others that I know I’m not aware of!).

Author Archives: admin

The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying

Marie Kondo’s book ‘The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying’ is definitely worth a read, especially for those with a general interest in the topic of introducing some order into a pile of chaotic objects, and also for those who have even a vague feeling that they would like to live in a tidier home. Her experience and passion for the subject jumps out from just about every page with an almost religious fervour. However, I’m happy to say that, towards the end of the book, she says quite unequivocally “tidying is not actually necessary”, “You won’t die if your house isn’t tidy”, and “tidying is not the purpose of life”; hence, for those with a desire to give it a go, she espouses doing a complete assessment of every item you possess as quickly as possible to get it over with. Having done so, she believes you will have a changed mindset, and that you will naturally continue to keep things in order.

While there are many points in the book that are of great relevance to the investigations in this blog, there are two major differences; the book makes hardly any reference to digitising things, whilst harnessing the power of digitisation is a key thrust of these investigations; and the book is focused on tidying ALL of a person’s possessions in their home (or their place of work), whilst this blog is looking at particular subsets of a person’s possessions. Having said that, the approach, rationale, and impacts that are described can all contribute to the understanding that I am trying to explore in these pages.

Kondo’s approach is pretty straightforward. Take a category of your belongings; assemble EVERY item in that category from EVERY part of your house, into a big pile; take each item, hold it in your hand, and decide if it gives you a spark of joy – If it does, keep it, and if it doesn’t, discard it; assign a specific space to store everything you keep; when you store things, make them as visible as possible, and avoid piling things one on top of the other. This process is intended to be a one-off, all inclusive, exercise to be done on every possession you have. In Kondo’s experience it usually takes about half a year.

The two key questions, of course, are what constitutes a spark of joy, and is having a spark of joy for an individual item the only criteria one should have. Take books. I love books and enjoy having them around me. Some of the individual books I have are less meaningful to me than others; but I’d keep them for the sake of having books on bookshelves around the house. Kondo doesn’t seem to recognise this. In the several examples she quotes about books, the outcome always seems to be the disposal of tens if not hundreds of books. To be fair, she does make it clear that the decision about what to keep has to be made by the individual concerned. I guess she would just advise that, in the absence of a spark of joy, you should be clear about why you are keeping something.

I don’t think I came across an explicit answer in Kondo’s book to the question ‘why bother to keep your house tidy?’. However, it contains a number of assertions which collectively suggest it’s a good thing to do. The simplest assertion is that one of the reasons why clutter eats away at us is because we have to search for something just to find out if it’s even there; so if we have a tidy house we can find things easily and quickly and feel more content. Another is that we keep things because either we become too attached to the past or that we have a fear of the unknown future. Kondo believes both things hold people back in their lives – being too attached to the past means that we can’t move on; and having a fear for the unknown future signals our reluctance to try out new things. However, Kondo’s overall rationale is even more complex than that. She believes that we fail to get to grips with clutter as an instinctive reflex to avoid thinking about the other issues in our lives. By discarding the things that are not truly precious to us, we are better able to see what is important to us; we are able to address the issues that are troubling us; and we can become more content with our lives.

Are any of these valid points? And if so, are they good and sufficient reasons for being tidy? To take each one in turn: a lot of clutter undoubtedly makes it more difficult to find things in most cases. However, there is anecdotal evidence that some untidy people can still find the things they need by having a clear memory of where they place things. In general, though, it seems reasonable to assume that being tidier can help many people find the things they need more quickly.

The notion that being untidy may be constraining people from moving on or from being able to try out new things, I feel is a more tenuous point: I think I have known many untidy people for whom these assertions are totally untrue. The best that can be said is that it may be constraining some people. As to whether a thorough tidy can help those people – well, according to Kondo’s experience with what sounds like an extensive client list, it seems that this is probably true.

Kondo’s final, rather bold, assertion that a thorough tidy can help us address issues that are troubling us and change our lives, is one that I have no way of assessing. Again, we have to rely on Kondo’s own experience with her clients – apparently, she has observed this occur many times, so we can only assume that, for some people who try out her approach, this is a possible outcome. Even if it’s only a possibility, for those who are seeking to address such issues, it may be a good reason to try out Kondo’s approach.

Now, turning to the impact that Kondo’s approach has on people, the most tangible and immediate impact seems to be the disposal of numerous bags of possessions. The numbers quoted are rather large:

- ‘I threw out 30 bags of rubbish in one month’

- ‘After three months of this strategy I had managed to dispose of 10 bags of rubbish’;

- ‘The minimum amount of paper waste that my clients dispose of is two 45 litre bin bags – the maximum so far is 15 bags‘

- ‘[one client] had no qualms about discarding and at our first lesson she got rid of 200 books and 32 bags of items.’

- ‘The record number of bin bags filled to date was by a couple who threw out 200 bags worth of rubbish plus more than 10 items that were too large to put into bags.’

- ‘The average amount thrown out by a single person is easily 20-30 45 litre bin bags and for a family of three its closer to 70 bags.’

These are big numbers and I found myself wondering a) if they are all shopaholics in Japan (where Kondo is based), and b) if they weren’t filling the bags to their capacity. But, anyway, it’s clear that disposing of such large amounts of stuff would probably make a very tangible difference in an average house.

Other impacts that Kondo cites are largely to do the mindset of the individual. She claims that ‘Tidying dramatically changes one’s life. This is true for everyone, 100 per cent.’ Particular changes she describes include the following:

- One of the magical effects of tidying is confidence in your decision-making capacity. Tidying means taking each item in your hand, asking yourself if it sparks joy, and deciding on this basis whether or not to keep it. By repeating this process hundreds and thousands of times, we naturally hone our decision-making skills.

- Because [my clients] have continued to identify and discard things that they don’t need, they no longer abdicate responsibility for decision-making to other people. When a problem arises, they don’t look for some external cause or person to blame.

- Putting your house in order will help you find the mission that speaks to your heart. Life truly begins after you have put your house in order. “When I put my house in order I discovered what I really wanted to do.” These are words I hear frequently from my clients.

- Through tidying, people come to know contentment. After tidying, my clients tell me that their worldly desires have decreased.

These are dramatic changes – but then the process that Kondo guides her clients through is also quite dramatic so perhaps it’s not unreasonable to expect some significant impacts on people’s lives.

So far I’ve really only spoken about the book’s general approach and impacts. However, it also provides a wealth of detailed and very useful guidance on how to deal with specific types of objects and on setting up different types of storage. There is too much material to discuss here, but I’ll finish this summary with just a couple of quotes which I particularly liked:

- A common mistake people make is to decide where to store things on the basis of where it’s easiest to take them out. This approach is a fatal trap. Clutter is caused by a failure to return things to where they belong. Therefore, storage should reduce the effort needed to put things away, not the effort needed to get them out.

- Mysterious [electrical] cords will always remain just that – mysterious.

What’s in a Name?

The term Order From Chaos is widely used in many different contexts. A quick search on Google reveals that it appears in areas as diverse as Heavy Metal music, foreign policy, and science. I remember coining my own use of the term in the late 1980s when, standing in the shower in Stoke Mandeville, I faced the fact that I would never be able to employ the acronym IFC (Interplanetary Freight Corporation), but realised that, with a small change of letter, I would have a name, OFC, which reflected a real interest of mine which I could explore, develop, and exploit.

While I haven’t come across any other people investigating this exact same meaning of the term, there are, nevertheless, some who are doing things that are closely related. Two in particular seem to be highly relevant and have books which are easily acquired and consumed: Marie Kondo (The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying: a Simple Effective Way to Banish Clutter Forever), and Liz Davenport (Order From Chaos: a Six Step Plan for Organising Yourself, Your Office, and Your Life). I’ve decided that I need to read these books before I set about drawing some general conclusions from the work recorded in this blog. My musings on their contents will appear in the next couple of posts.

DuvBag

If you want to use your own bedding while you’re away, a duvet with a built in undersheet – rather like an oversized sleeping bag – would do the trick. It would also eliminate the need for the people you’re staying with having to wash the bedding after you’ve left.

OFC as a Service

When I first started thinking seriously about these OFC ideas back in 2004, I set about trying to turn an intuitive art into a clear repeatable process. I produced three documents of which only the White Paper has appeared in this blog. The other two are essentially draft documents which have not been properly tested and refined; however, I’ve decided to include them here as they do at least provide an indication of the sort of detailed activities that OFC entails. They are a Service List and a Process List. Both incorporate the notion of charging for the service – though that is by-the-way; I no longer have any ambitions to create a business, though I would dearly like to be able to try out my ideas on some real world collections of objects which belong to someone else and with which I am not already familiar. The OFC exercises documented within this blog have been informative but are almost certainly not sufficient to be able to define a fully generalisable process.

I have applied OFC techniques to one set of material that was not my own: it consisted of 6 large egg boxes containing the stamp collection of an old friend’s mother who had died. My friend is not a stamp collector and was having trouble disposing of the collection. I am a stamp collector so I was excited by the prospect of both exploring the collection and having the opportunity to apply some OFC techniques. In my first encounter with the material I took about three hours to go through it all, divide it up into the major categories, and get an overall picture of what it consisted of. I agreed with my friend that I would sell the material through Ebay, so subsequently sorted it into sub-categories that I thought would interest potential buyers. I ended up with approximately 37 Lots which I proceeded to sell on Ebay over a 3 week period. For each Lot I took photographs and wrote a description for it’s Ebay entry; and I managed what I was doing in a Word document which contained the following information for each Lot:

- Ref No

- Title (for use in the Ebay entry)

- Description (for use in the Ebay entry)

- Two or three of the 12 free photos allowed by Ebay

- Weight (for use in estimating postage costs)

- Size (for use in estimating postage costs)

- Postage (type of service and cost)

- Date put into eBay

- Disposal if not sold in Ebay (which could include ‘re-list in Ebay’)

- Date auction ended

- No of bids

- Amount paid by buyer

- Paypal fee

- Ebay fee

- Packing costs (if any)

- Actual Postage Costs

- Net amount after all expenses

- Date sent

- Buyers name and address

I was able to give a copy of this document to my friend as a permanent memento of her mother’s stamp collection. This was an instructive experience, and I continue to look out for other opportunities to try out OFC techniques.

Berko Dérive

A week ago I had a taster of how to explore intuition. It wasn’t something I’d signed up for, or even expected. It was just a catch-up meeting after about 15 years with my friend Clive Holtham of City University’s Cass Business School, who had originally helped me establish my electronic document management system, and with whom I have had many thought provoking and inspiring conversations about new office technology and its uses. I figured that, after five years of doing Order From Chaos stuff, it was time for another dose of reflections, imaginations and nugget exchanges with him. I wasn’t disappointed.

We had arranged to meet outside Berkhamsted station at 09.53, and the first thing we did was have coffee in the station’s high ceilinged and rather grand, in an old style renovated with 5 video cameras focused on every doorway, sort of way. We sat down and with little ado Clive provided me with my A5 journaling notebook and my Derwent Water Brush Pen for enhancing crayon marks. He gave me a tour of the crayon pencils and water based crayon pens and the pencil case we were to share, all the while explaining how we were going to journal our Dérive (check it out in Wikipedia) through Berkhamsted and why. Interspersed, of course, with both our numerous questions, accounts of our experiences, and our descriptions of related work.

We started to write, or, I should say, crayon and brush and illustrate, our journals. I noted that Dérive involves Noticing, Conversation and Storytelling (using the five senses, as Clive alerted me during our walk). When I started describing my Order From Chaos activities, Clive immediately chipped in saying that we need more Chaos, not less, to get us out of conventional thinking and rote responses. A few exchanges later we agreed there is probably a compromise to be had. Clive advised me to look out a David Snowden paper which directly addresses getting order form chaos (and includes a model) which clearly I shall be looking for very shortly in Snowden’s ‘Cognitive Edge’ website. I used a page to write down VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) and to highlight its distinction from the conventional and craved-for utopia, SCSC (Stability, Certainty, Simplicity, Clarity).

Eventually we started our walk and found ourselves on the tow path of the Grand Union Canal. We continued to talk; we stopped, admired, examined, exclaimed, took photos (Clive takes many photos and stores them all in dated folders) and drifted on. We came across an access cover to the fibre optic channel laid along the tow path of the industrial revolution’s super highway; and we encountered two brass rubbing plates describing Berkhamsted history with a notice advising us to visit a website (our equipment proved not to be up to brass rubbing so we resolved to obtain charcoal and sugar paper at an art shop if we could find one). We spoke to a lady about the butterflies and pleasantness of the place; we discussed architecture; we saw a very large monkey in a conservatory (almost certainly not alive); we talked about art deco on the high street; and we encountered more monkeys in an antique shop and noted a pattern. We went in to an art shop which told us that, no, they didn’t have charcoal or sugar paper (brass rubbing plaques on the canal – oh really?!) but that there was an art and craft shop further up the high street which almost certainly would have them.

For lunch, we took up the offer of doing market research on fizzy drinks and duly sampled three different versions of three different drinks (I had Cream Soda, Ginger Ale, and Fizzy Orange)and were asked to provide all sorts of complicated observations about how they looked and tasted (Clive deliberately used all his five senses) in answers involving the five possibilities very good, good, average, not so good, poor (or equivalents); and which eventually one couldn’t distinguish between and just became approximated to average so that we could get to the food part of lunch which was a chocolate bar or chewy sweets for our troubles.

We found the art and craft shop which turned out to be a veritable cornucopia of different and unusual stationery items of immense use in the pursuit of Art-Based Management Education and Order From Chaos exercises. The Assistant helped us with charcoal, and the Proprietress sorted out our paper (two particular types just to be sure) and we left satisfied that we could now rise to the challenge of canal-side rubbing. Outside the Art & Craft shop, I asked Clive if he had heard of ArtRage and he said he’d been using it for the last ten years – an excellent product. I mentioned that my son was the owner (I should really have said joint owner – well, joint developer, builder and owner) and we laughed, amazed at the connection.

Outside the sun continued to shine. We found another place to park the car – this time for free and by the canal. We sat on a bench to put more stuff into our journals and I watched a man on the grass, thirty feet away, tickling a swan on its side while it pecked his other arm as if licking the salt like a dog would do. It was something I had never seen or even imagined. We crayoned and discussed, and drew and brushed the water paints. We talked about Buckminster Fuller, about hexagons (so much better for fitting together than Post-Its,) and about encouraging students to first do Notetaking, then to do a quick read with Basic Reflection; and finally to undertake Deep Reflection. Clive remarked that Schools progressively remove imagination from pupils and that any that is left is surgically removed by the universities.

Eventually, we had another stroll along the other tow path and found curious outdoor gym equipment without instruction but maybe for back stretching. Then we came across another brass plaque. Clive attacked it with gusto, trying first the thinnish paper with the charcoal (just didn’t work) then triumphing with a black crayon on the newsprint paper. With this victory documented in several photos, we found our way back to the car, drove to the station, and had an ice cream before Clive caught the 4.01 to London. I drove home with my Journal, my Water Brush Pen, my 40 rouble Water Colour Pallet, and an A7ish booklet of the Reflective Practitioner Exhibition 2017 printed by Boots from a Snapfish account.

Of course the above description can’t convey the richness of our conversation nor the extent of our exchange of knowledge; but I hope it paints the dreamlike context with which our minds were opened and new pathways were discovered – just as Clive intended. Days like that don’t come around very often; so it will stick in my mind and will ooze out across my thinking for many days and weeks to come; and will almost certainly colour my thinking about this particular Order From Chaos journey.

Cover Art

The Sounds for Alexa book is nearly finished now with its leather cover on and only the end papers to stick down. I’ll describe these final stages in a subsequent entry when it’s completed. In the meantime, with the outside dimensions of the book fixed, I’ve been able to get on with the cover.

The dimensions of a book cover pose a bit of a problem since they are much longer than the normal paper that you can buy to print on. This particular cover will need to be 21 cm high and some 53 cm long. I was able to solve that problem by remembering the roll of surplus wallpaper lining paper that I had stored away in a poster tube for our grandchildren to draw on at some point in the future. It turned out to be sufficiently strong for a book cover but pliable enough to go through the printer – a delicate balance I’d fallen foul of before when trying to print things for weddings. Setting up the printer wasn’t a problem – you just set a custom page length (of up to a maximum of 676 mm in the case of my printer) and the printer will chug away and print the length you desire.

I decided to create the cover in Powerpoint and started off by setting the page size to be about a centimetre each way larger than the actual dimensions I needed because the printer usually leaves a blank border area of at least half a centimetre around the edge of the page. I figured that if I made the picture a little bit bigger than I need I’d be able to cut off these blank edges to get the exact size required.

Ever since deciding on the book’s sub-title – ‘A listing of Su and Paul’s digitised LPs, Cassettes, Tapes and CDs for use in the marriage of Alexa to Aye Fon’ – I’d had a picture in my mind of a wedding ceremony between our Amazon Echo and my iPhone surrounded by the turntable, ghetto blaster, and laptop, and all the digitised LPs, singles, cassettes and CD’s which I now retain in the loft for proof of ownership purposes. I took a look around our house and decided our patio would be the place to take this photo, and took some experimental shots to see where things should go. This transpired to be very important because the title down the spine turned out to be in a part of the photo which had a brick wall in shade and consequently the black of the title was lost in the black of the shade.

I did some more experimentation and finally fixed upon an appropriate angle to take the shot, and waited for a sunny day. I knew it was going to be quite a big job laying out all the technology, LPS, cassettes and CDs on the patio and wanted to minimise the time they were left in the sun in case they got heatstroke, so I enlisted the help of my son and his wife to help in the photo-shoot and get things laid out and back inside as quickly as possible. We did the shoot on the 2nd July which turned out to be particularly hot so we really did need to work as quickly as possible. However we managed it and got several shots and got all the stuff back in the house and packed up in its boxes ready to go back in the loft. Quite a palaver – too much of a palaver to have to do it again – so the pictures had to be right.

Well the pictures were OK and I did manage to get a cover – but, in the heat of the day and the moment, I made some errors which I guess a professional photographer would have picked up on straight away. I thought I would be able to enlarge and move the picture in powerpoint to get the exact position for the text for the spine. However, this proved to be very difficult without cutting off a substantial part of the key elements of the photo. What I should have done is taken the picture from further away. My experimentation had not been detailed enough and my photography had been inexperienced and rushed. Such are the differences between the amateur and the professional.

Nevertheless, I was able to choose a photo which minimised the problems and which I was able to get the spine title in what seemed to be a fairly readable position. For the inside flap texts I lifted some extracts from previous posts in this blog, and then I was all set to print out a copy and see how it looked and fitted. The result was OK but there were some issues with the position of the title down the spine (it still went into some shaded areas where the black text wasn’t as clear as I would have liked); and the text on the back flap was a little too far away from the edge of the flap. I made the spine text smaller and adjusted the position of the back flap accordingly. However, a more intractable problem was that the picture simply wasn’t high enough; there would have to be a few millimetres of white space at the top and bottom of the cover because the print had been produced with a border. I started to explore the print options and eventually came to the conclusion that borderless printing – which is what I needed to get the height I required – is unavailable for anything other than smaller Photo Papers. My printer simply does not support Photo Papers of 220 x 570 mm (which is what I required); and does not support Borderless printing for anything other than Photo papers.

I compromised. I abandoned the quest to enable borderless printing and elected instead to go for High Resolution Paper and High Quality. The result still had a few millimetres of white border at the top and bottom of the cover, but the title was now clear and the print quality was noticeably better. I decided to quit while I was ahead. So my final print settings were:

- Media Type: High Resolution Paper

- Print Quality: High

- Page Size: Width 200mm, Height 570mm

- Printer Paper Size: Width 215.9mm, Height 570mm

- Orientation: Landscape

The image I printed is shown below.

An OFC Model

I’ve completed my quick trawl through all the entries in this blog looking for insights about Order From Chaos. Whenever I came across some relevant text I copied it into a spreadsheet and then allocated one or more categories to it. The categories were not pre-determined – they developed as I went through and I ended up with about 20 of them. I also checked the OFC White Paper which I produced in 2004. With all this as background I set out to try and produce an updated view of what I mean by Order from Chaos in the light of my experiences over the last five years. Here’s my first attempt:

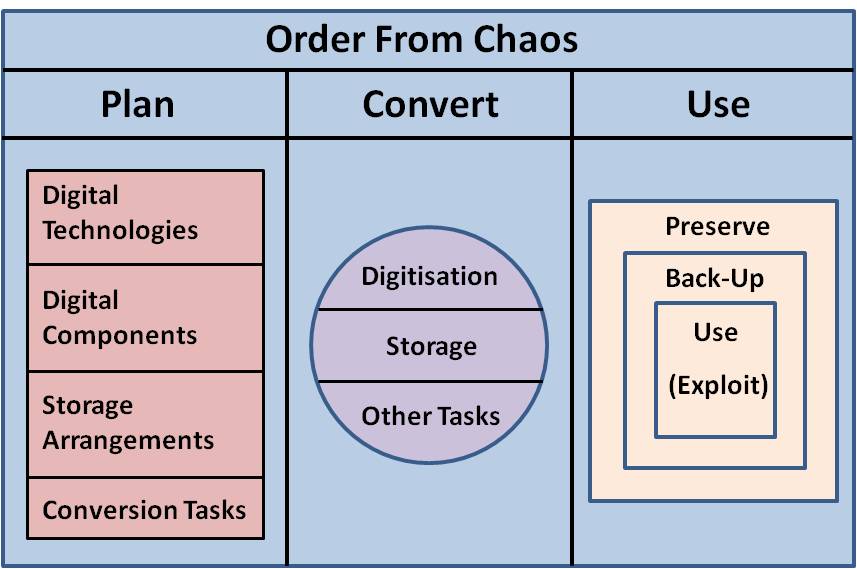

Order From Chaos (OFC), in this context, refers to the organisation of any set of things with the assistance of digital technologies. Examples of such things include: Music Collections, Loft Contents, Family Photos, Household Files, and Letters. Such material usually (but not always) starts out being in a purely physical form. Therefore, undertaking OFC usually entails some element of Planning followed by a Conversion process. The result may be purely digital or a hybrid of both physical and digital. Either way the newly organised material can be put to use in its new form, and possibly reproduced in different forms. Any new digital components will require Back-Up and Preservation procedures to be applied.

The Planning that needs to be done usually includes the identification of the digital technologies to be used; the design of necessary digital components such as file title formats and spreadsheets; a description of the storage arrangements for both physical and digital components; and an outline of the conversion process that is to be undertaken.

Conversion involves digitising the physical components, implementing the storage arrangements, and doing anything else that is necessary to ensure that the transformed set of material can be easily and effectively used.

Back-up procedures need to be put in place to ensure that both the physical and digital components are protected from loss.

Preservation procedures need to be put in place to ensure that the digital components do not become obsolete and inaccessible, and that the physical components do not deteriorate.

These concepts are all represented in the model below. When OFC techniques are applied to a new set of things, each of the items in the model needs to be addressed.

To test the usefulness of the model I’m going to apply it retrospectively to the OFC transformations I have reported on in this blog.

To test the usefulness of the model I’m going to apply it retrospectively to the OFC transformations I have reported on in this blog.

The Printing Solution

Pwofc.com was born 5 years ago and, as it has covered more topics and grown in size, the likelihood of being able to reconstitute it should some disaster occur, seems to becoming increasingly remote. So, when I started to systematically go through every entry in the blog to tease out OFC insights, it occurred to me that I could, at the same time, copy the contents into a word document which could subsequently be printed and bound into a hardcopy book in just the same way as the Sounds for Alexa book has been produced. That’s what I did, and I now have a 227 page document containing the main contents of the site. I now need to add in the 40 Appendix documents which have links from the main text. The final book may well have around 400 pages or more – but that shouldn’t present a bookbinding problem.

I haven’t established yet whether there is a standard website archiving solution which makes it easy to reconstitute and access a site; however, even if there is one, I think I shall feel more comfortable knowing that I actually have all the content in a single backed-up file. I shall feel even more comfortable when I have the book of pwofc.com in my bookcase.

Droid explorations and DMS alternatives

Things have started to move in our efforts to perform digital preservation on the PAWDOC collection. I’ve been running the National Archives DROID tool across the 190,000 files and Ross’s automated analysis of the results has turned up a number of issues including several hundred duplicates which we are investigating. Among other things, DROID identifies file types and versions, and this has helped another strand of our investigations to try and gain access to about three hundred files which can no longer be opened. 150 of these are old PowerPoint files from the early 90s which neither the Microsoft viewer nor the earliest version of OpenOffice can open. However, the Zamzar online service, to which you download a file and specify what format you want it to become, successfully converted all of the examples which I submitted, into a version of Powerpoint I can open. Zamzar can’t deal with every problem file, especially those for which I no longer have the relevant application, for example, MS Project and iThink, though it did convert Visio drawings into PDF. We’re continuing to work through these files with the intention of getting a clear decision about what to do with each one so that specific actions can be included in our eventual preservation project plan.

Another substantial investigation underway is to try and identify a suitable alternative to the document management system (DMS) that controls the collection’s files. The future of the current DMS is uncertain, and is too complex to reinstall on upgraded hardware without expensive consultancy support. Jan’s exploration of alternative DMS and preservation repositories, highlighted the fact that, while there are several free to use public domain systems available, they all require multiple components and appear to be relatively complex to install, configure, and maintain. This observation has prompted me to be a lot clearer about the immediate requirements for the collection. It is hoped to find a long term owner, perhaps working in the field of modern history, and it’s possible that that person or organisation may require more sophisticated search and access control functions. However, until that eventual owner is found, only a minimal level of single user functionality is needed, and minimal system management and cost demands are essential. In light of this greater clarity, we are now also considering a low tech, low cost alternative which would involve inserting the Index reference number into the title of every file and storing all the files in the standard Windows folder system. After identifying a required Reference No in the Index, files would be accessed by putting the reference number into the folder system’s standard search facility. As well as looking at the pros and cons of such a solution, we are also investigating the feasibility of getting the necessary information out of the current DMS and into the titles of all the document files. A further challenge that would have to be overcome is that the current DMS stores multi-page documents as a series of separate TIF files. If we were to move to the low tech Windows folder system solution, it would first be necessary to combine the files making up a single document into one single file. This would need to be an automated process as there are too many documents to contemplate doing it manually.

All these activities and more are required in order to be able to assemble a project plan with unambiguous tasks of known duration. We are continuing to work towards this goal.