The obvious way to dispose of physical DVDs and yet still have them available to view is to convert them to digital format and to store them on a PC or hard drive. In theory, they could then not only be copied to and viewed on any device (such as a tablet or phone), but also viewed on a large screen TV via the domestic wi-fi network. To explore these possibilities, I downloaded the free open-source HandBrake video converter tool (as recommended in issue 664 of the UK ComputerActive magazine).

HandBrake complies with Digital Rights Management (DRM) legislation and so is not able to circumvent standard copy protection measures built into most movie DVDs. However, a separate piece of open-source software called libdvdcss-2.dll is freely available to overcome this problem. This is effectively a plug-in to HandBrake and simply needs to be placed into the HandBrake program folder. I duly installed both HandBrake and libdvdcss-2.dll and set about trying to convert some DVDs.

I had a minor problem getting started as, after completing my first conversion, Handbrake seemed to be unable to read a large number of the DVDs. I eventually found that the problem was something to do with pointing to the correct file for HandBrake to inspect: I’d been selecting the “D: DVD name” entry in the Source Selection menu, and this was producing a screen announcing “No valid source or titles found”. The problem was rectified by choosing the Folder option in the Source Selection menu and then selecting the “D:DVD name” that appeared in the Windows Explorer menu. I don’t really understand why this made a difference – but everything worked fine doing it that way….

Overall, I found ndBrake very easy and effective to use. It was able to read all but one of the 54 DVDs in my collection. The one that it couldn’t handle was designed to enable the downloading of a copy of the film ‘Minority Report’ so there was actually no film on the disk for HandBrake to identify. I was unable to even try to convert any of the four Blu-Ray titles in my collection as my DVD player simply won’t read them. In the course of the exercise, I successfully converted 19 of the 54 DVDs to MP4 using the standard presets advised by HandBrake, and encountered no problems in doing so with each conversion generally taking between 20 minutes and half an hour. I shall comment on the quality of converted files later on in this process after I’ve tested viewing them on my TV.

I decided to limit the number of DVD conversions at this stage because of the time required to undertake the conversion, and because of the large file sizes being generated. The films I have converted are either ones I created to get me started with HandBrake; or ones I definitely know I want to keep; or ones that I want to see before deciding what to keep. The 19 titles I converted take up some 18.5 Gigabytes and play for a total of about 40 hours. I shall return to the question of what converted DVDs I want to keep after I’ve investigated some related issues such as whether they can be easily obtained through streaming services, whether the converted files play successfully on the TV via wi-fi; and whether the quality of the converted files is good enough.

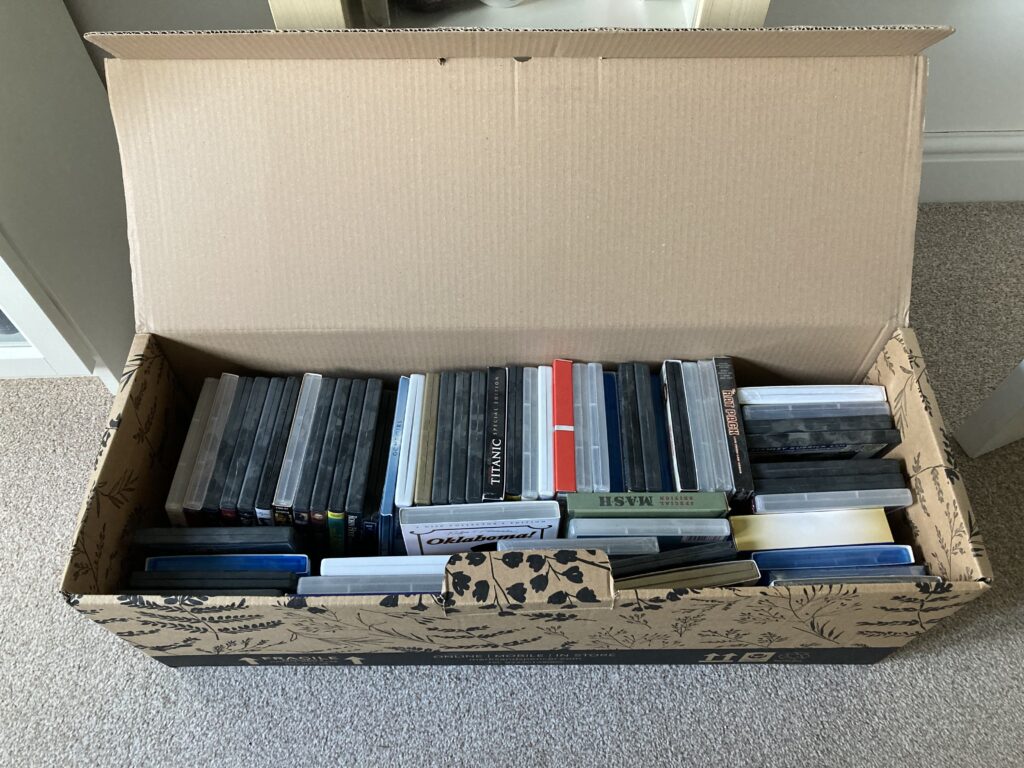

One final note on the converting experience: I’ve had to handle the DVDs a lot during the process and this has definitely induced a sense of appreciation of their characteristics. No doubt this is partly due to the stirring of good memories of some of the films; but its not just that. These products with their different designs – triple fold overs, slip cases, multiple DVD holders, metallic casings, eye-catching graphics, special editions, and the odd booklet – do have their own kind of kudos. But I must restrain myself… we’ve decided to dispose of these physical goods and that’s that…..