In a previous Loft post I concluded that I didn’t need an RFID capability. So, with that question out of the way and having explored most aspects of operating a Loft system over the last 20 years or so, I’ve decided it’s time to draw some conclusions and to move this journey onto the Kcompleted list.

Key facts and figures

First, here’s a summary of the design of the system, the contexts within which it has been used, and some approximate overall statistics about its use in the 20 years between 2005 and 2025 (note that estimates have been used to compensate for errors and omissions in recording – see errors section below).

- The system involves placing numbered Items or Containers into labelled Positions. All Positions, Items and Containers have an entry in an index.

- Lofts in two different houses have been used – both affording 32 different Positions between the rafters.

- During the period there have been two adults living in the house, 2 teenagers growing up and leaving home, and one elderly relative staying for 6 months in the course of moving. All these individuals have contributed to the loft’s contents.

- About 469 items were indexed of which 352 were removed after an average stay of about 5 years. The 119 items currently in the loft have been there for an average of about 9 years.

- About 91 Containers were indexed of which 57 were removed after an average stay of 8 years. The 35 Containers currently in the loft have been there for an average of about 13 years.

- Just 16 of the items and 10 of the Containers which were indexed when the Loft system was first setup in January 2005, continue to be present in the loft after 20 years.

What to keep and where to keep it

Although this journey has focused on Lofts, the findings can be applied to any domestic storage area – a garage, a spare room, an outhouse etc. The investigation has been about using such spaces to store items which are not in day-to-day use but which a householder wants to keep. Deciding what to keep and what to throw away is central to this activity, and I think I’ve usually erred on the side of keeping. However, I’ve also found that over a period of years I’ve changed my view on some things and disposed of them. So, a periodic review of the contents can be worthwhile.

There are some general criteria which I’ve realised are worth considering when deciding to store things in a loft, a prime one being, will it go through the loft hatch? Others are: If the object is of great sentimental value wouldn’t it be better on show in the house than buried in the loft (for example two inscribed tankards)? If the object is useful, wouldn’t it be better somewhere accessible in the house (for example spare stationery items).

I’ve also found that sometimes I’ve tended to keep things in the loft longer than needed simply because they are difficult to dispose of. For example, pieces of an expensive shelving system which we are unlikely to ever have a use for, but which we can’t find anyone who wants them and which seem too good to simply take to the dump. For such objects, I think it’s probably better to take a decision than to procrastinate for years – though that’s sometime easier said than done. Some disposal problems can be purely practical such as the need to cut up over 100 CD data disks – a task which I spaced out over several days because it hurt my hand using the heavy-duty scissors.

Of course, in a family household the items being stored may belong to different individuals. In our case about 58% of the items were owned by myself and my wife, about 36% by our children, and the remaining 6% by an elderly relative. Of course, we experienced the typical problem that parents have when their children move out – getting them to remove all their belongings. We still have some things that we believe are worth keeping but the individual is reluctant to take.

Designating Containers and general packaging considerations

The system I’ve been operating requires the objects being stored to be designated as either Items or Containers. Containers might be empty (like suitcases), or contain other Containers (such as a small suitcase in a large suitcase or a small box in a large box), or contain one or more Items. Items may be one individual thing (like a card table) or a collection of several things (such as 100s of music CDs). When I initiated the loft system, I tended to separate Containers from Items quite rigorously. For example, the box of old Rolling Stone and Boy’s Own magazines was indexed in two parts – C7 for the cardboard box they were in and Item 10 for the magazines. Now, some 20 years later I have removed the Container C7 from the index and relabelled the combined box and magazines as Item 10: the reasons being that a) the box is only ever going to be used to house the magazines, b) looking up the reference on the Container label just tells you what the container is, but having a combined item number on the label on the box enables you to find out what is being stored, and c) managing two index entries when just one will do is just extra unnecessary work.

I recount these details as I’ve realised that deciding whether to combine container and item or to keep them separate is important because it can help to minimise effort and maximise usefulness. The rule of thumb I now apply is that if the contents are to be indexed as a single Item, and if they are likely to stay in the loft for several years, then I combine the Container and the Item, and index and label it as a single Item. An addendum to this is that if one Item consists of several objects of the same type it is probably more effective to store it on its own: that way it will be easier to manage and to find.

Regardless of the above deliberations, I always try to enclose Items in some sort of packaging to avoid them getting dusty and/or eaten by rodents. Over the years I have used suitcases, cardboard boxes, tubes, shoe boxes, plastic bags, long transparent solid plastic containers, and long bags that carpet comes in. Some of these have been indexed as Containers and some have just been made an integral part of the item. The Items I have stored without any covering are usually pieces of furniture (like a coffee table, wallpaper table, or kitchen chairs). Generally speaking, I’ve found it best to store Items with minimum folding or rolling because over the long term those characteristics temd to become embedded in the objects concerned. I have facsimiles of two old copies of The Times rolled up in a tube, which have to be held or weighted down to stop them from rolling up again when they are being read. I’ve also stored large sheets of bookbinding cardboard upright in a cardboard box leaning against a rafter, but over time the box and the boards bent. All of these items would have benefitted from being stored flat.

Managing the organisation of the physical objects in the loft

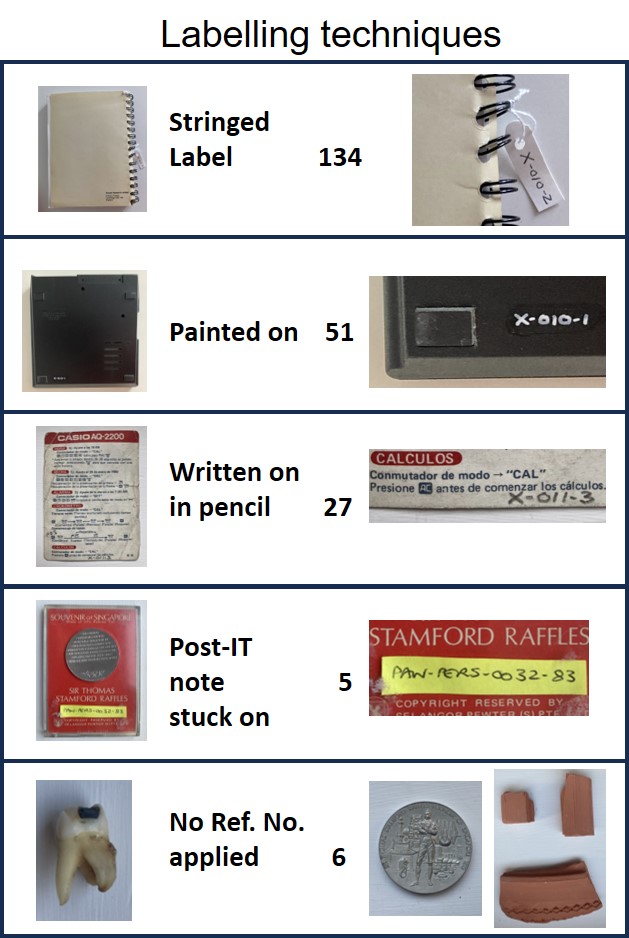

It is important to clearly label the Positions where the Containers and Items are to be placed. The Positions should be clearly differentiated from each other so there is no ambiguity (I use the loft rafters as the delineator) since it is the Position numbers that enable the Items to be found. Containers and Items should not be placed across two or more Positions except in special circumstances (for example, I have a large number of spare empty boxes which are indexed as a single item but which fill 3 separate positions).

I write Container and Item labels on both sides, and I place them so that their labels are showing and closest to the front of the position. To facilitate this, I take care not to stack too many Items or Containers on top of one another or behind each other. This also helps to minimise the number of Items/Containers that have to be moved to access the one you want. If an Item consists of more than one object I package them together with a single label; however, if the objects are not packaged together, I give each one the same label with the same information. Of course, it is important to label an Item or Container with the correct label as specified in the Index.

I have found that, over time, Items consisting of large numbers of the same things (particularly packaging Items such as a box of small boxes, or a collection of boxes) may get very disorganised and need sorting out. In doing so I take the opportunity to discard unwanted items, and to organise the objects in such a way that they are easy to see and access.

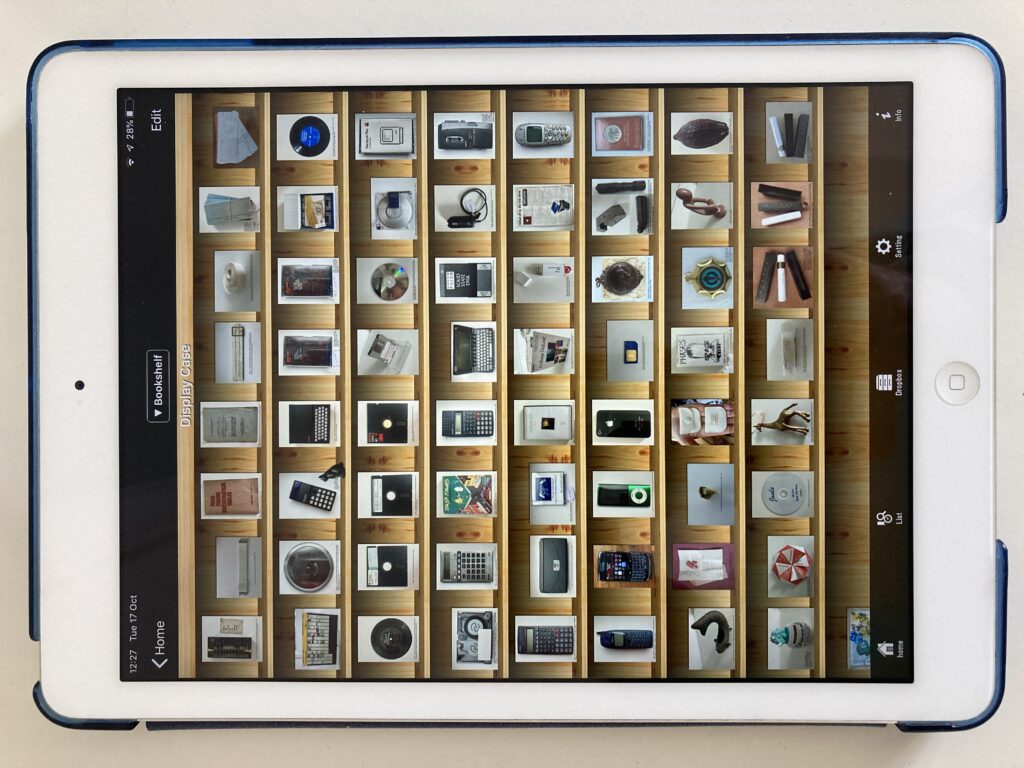

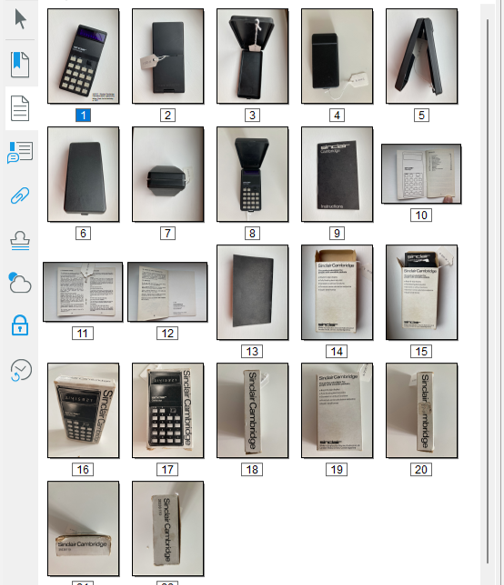

Managing the Index

I personally think that an Index is essential when operating this kind of loft system. Having tried operating an index on both a laptop and a mobile phone, I would definitely advise having one on a mobile phone since it can be taken with you and used on the spot when you access items, change their positions, and make changes to their contents. A variety of suitable database apps are available (see my earlier posts on this issue), most of which will enable you to specify whatever fields you want. The fields I am currently using are: Description, Type, Item Serial Number, Container Serial Number, Position Serial Number, Item Category, Item Owner, Item or Container condition, Container this Item or Container is placed in, Position this Item or Container is placed in, Date this record was created, Container Security Status, Date removed from loft, Photo. I believe a photo is essential – and, of course the app should enable you to use the mobile phone’s camera to capture the image.

I try to ensure that every object in each Positions is included in the Index – unlabelled objects may get forgotten about and effectively lost. I also try to ensure that all changes to Containers and Items are reflected in the Index; and, indeed, the flexibility of the Index makes it easy to accommodate such changes – you just have to be diligent and remember to make the changes. However, being the humans that we are, we sometimes forget, and we often make mistakes – as described in the next section.

Errors in operating the Index

I’ve made many errors in the course of using our loft system, and perhaps the most common has been simply not updating the Index when a change has been made or an Item has been removed from the loft. This problem is often exacerbated when other people (such as offspring!) who are not so aware of the system or committed to its upkeep, are involved. However, even when I have remembered to make changes, I have sometimes updated records incorrectly. Indeed, I know I have actually created some Index records with incorrect information, though, so far as I know, I have only duplicated an Item number once.

In short, unless you are super diligent, you will probably make some mistakes in the course of operating a loft system. Therefore, it is useful to do a stock check from time to time – maybe every five years or so. Doing so also provides a useful opportunity to reassess whether you do actually want to continue to keep storing some of the items being checked.

General Approach and Best Practice

- Find an Index app for your phone.

- Specify the storage area and the positions within it.

- Index the positions and label them.

- Try to enclose Items to be stored in some container or packaging to prevent dust and rodent damage.

- Record every Item being stored, in the Index.

- Where items consist of many of the same objects and are to be stored for the long term, combine the objects and their container into a single Index Item.

- Include a photo of every Position, Item and Container in the Index, but keep a separate set of Photos elsewhere in case you need to change apps (exports are usually available in transferable csv format which is unlikely to include photos).

- When changes occur to the physical Items and Containers, make the associated Index changes immediately on the phone.

- Undertake a stock check every 5 years or so and while doing so consider disposing of unwanted Items or Containers.

Conclusion

I’ve found our Loft system to be a very useful and effective way of storing the large number of things that we don’t need on a day-to-day basis. However, it does take time and effort to set up; and it does need diligence to keep the physical space in order and to keep the index up to date with the changes that are made. The mobile phone has made operating such a system a much more practical proposition.