Since retiring in 2012, I’ve been gradually sorting out my work documents and books (see the Personal Document Management, Electronic Bookshelf and Electronic Story Board journeys), and in the process have been finding things I’ve had published and putting them in a holding location on a shelf. I’m not an academic, so I have never had a career incentive to publish papers; I just got into the way of doing it when I had a job at the National Computing Centre in the early 80s which entailed seeking out best practice in Office Automation and feeding it back into UK industry via books, articles and talks. So, now, with at least 30 or 40 papers and books to my name, I’d decided to try to make sure I had a copy of each one.

My plan was to keep all the originals for my own sense of satisfaction (as already documented in the paper produced in the Digital Age Artefacts journey – they fall into the category of ‘Items that the owner has written, produced, assembled or made a significant contribution to’). This physical set of material would have an equivalent electronic version which would reside on my iPad for easy access and to enable me to possess copies if, at some time in the future, a lack of space or changed circumstances prevents me from having the physical versions on hand. The collection would be controlled by adding serial numbers (1, 2, 3 etc) to the publication list that I’d been maintaining since the 1990s, and using that as an index. This would enable each physical item to be labelled, and each electronic file to have the serial number included in its file title thereby ensuring that the iPad items would be displayed in chronological order.

Over the days that I was developing this approach, I also spent some time thinking about whether this material would be of any interest to my family after my decease. I concluded that probably only the books I had published would stand a chance of being retained. Large published tomes of conference proceedings which include 9 or 10 pages of a paper I had presented would almost certainly end up in a charity shop or auction lot. As to whether the family would want to retain the electronic collection downstream, it’s difficult to say. They would certainly find the electronic version easier to curate; but whether there would be the interest to do so is an unknown.

With my plans in place, I set about a process of taking each item on the index, finding the physical publication, obtaining an electronic version from my files or by scanning the original, and storing it as a PDF with its number, name and date in the file title. It turned out not to be so straightforward. For a kick off, several of the physical items that had been assembled on the bookshelf weren’t on the index and this wasn’t discovered until part way through the job. Consequently a certain amount of renumbering had to be done midstream. In retrospect, it would have been more sensible to start off by reconciling what was on the shelf against what was on the index. Other complications included:

- for some of the entries in the index, there wasn’t an equivalent hardcopy on the shelf and I had to search out a version from my work files.

- for some items, the original publication wasn’t immediately to hand so a search had to be conducted through the work files and, If it wasn’t found, a decision had to be made as to which version of the piece was to be used.

- for several items the original was in a book, requiring a scan to be made of those pages by placing the open book on the scanner platter and pressing down to obtain a usable scan of each page. These scans had to be refined within a PDF editor to crop out black areas round the edges and to assemble the pages in the correct order within the final PDF. For two of the books I’d written, a spare copy was not available to cut up and put through the sheet feeder; so I had to deal with the whole of the two books in this way.

For a number of the papers, it was not clear whether or not they should be classified as publications and included in this set of material. For example, I excluded some reports I had produced for the UK Alvey Programme Cosmos project on the basis that they were very project specific and had to be requested from a published list. Other types that did make it through my somewhat arbitrary criteria were:

- conference papers for which I wasn’t able to determine if any proceedings had actually been published or if my paper had actually been included

- workshop papers presented at conferences but not included in any proceedings

- a paper and a book review published in the British Library’s experimental electronic Journal Blend system in the 1980s

- a spiral bound state of the art report for NCC’s Office Technology Circle

- papers rejected by journals

- papers completed but not submitted for publication

- an article which I wrote but which was presented in a promotional booklet not as an article by myself but as a case study about me

- a fully integrated online tutorial on HCI in 27 parts presented over the internal network of the company I worked for and accessible to its 90,000 employees worldwide

- a so-called White Paper describing what I meant by ‘Order From Chaos’ and published in an early version of this OFC website.

I suppose the overriding criteria was that the piece should contain novel material with general applicability, was produced as a complete and coherent whole, and was made openly available – whatever all those words mean! In fact, I guess I just included the pieces I wanted to….

One other point is worth noting: wherever possible I included a scan of the cover and contents of the publication that the paper appeared in, or of the event that the paper was produced for, at the end of the PDF. This was done because the book covers on the bookshelf, or the event details, provide some kind of identity for the papers. The contents were included to provide a clear indication of the context within which the papers were presented and their exact positions amidst all the others

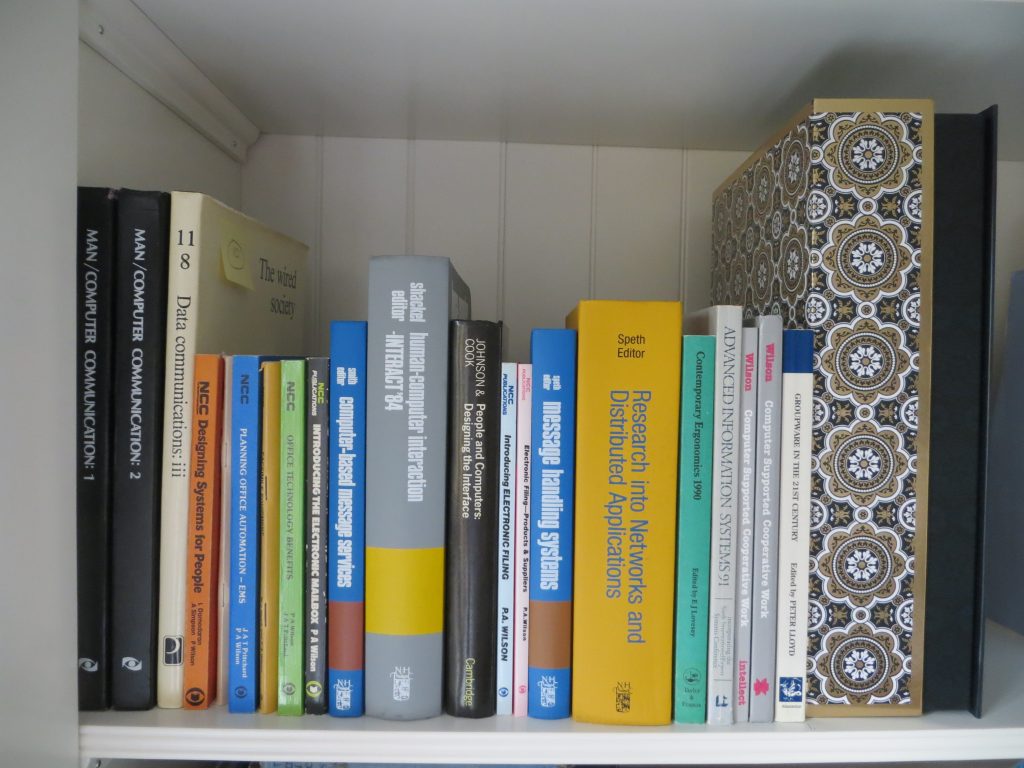

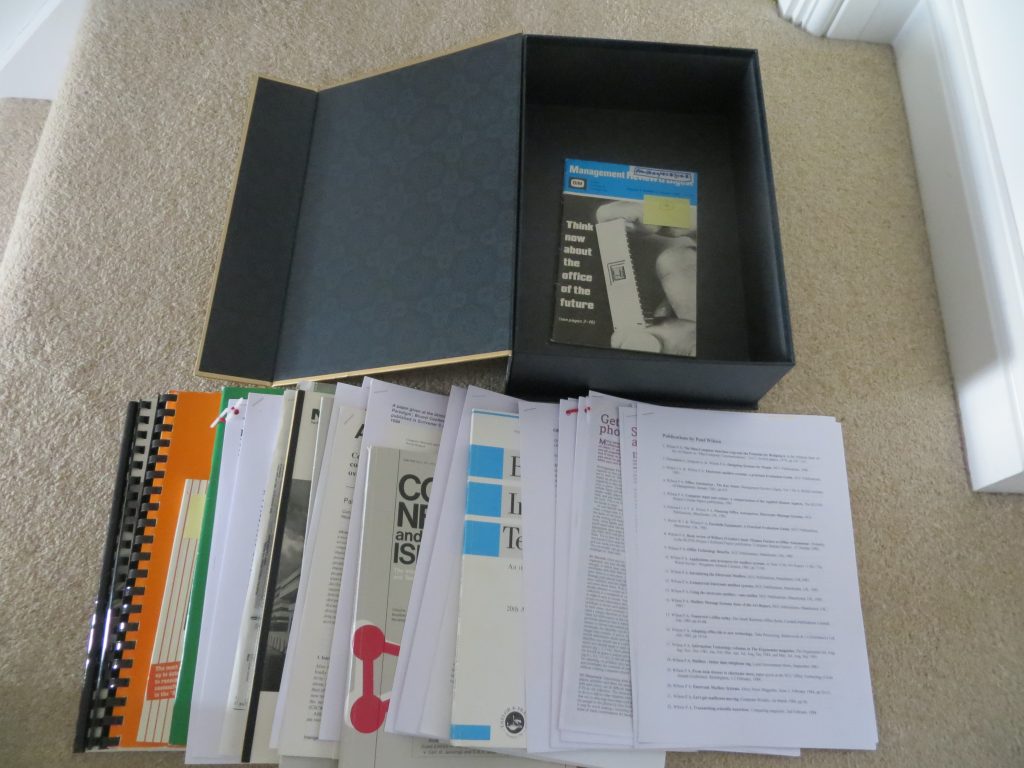

Having been through all the material, I ended up with some 61 items in the index, 61 separate PDF files, 19 physical books, and a box file containing the other 42 papers in journals, spiral bound publications, and print outs – as shown in the photos below. The box file was essential to store those items which would otherwise just flop about on the bookshelf.