It was probably early in 2023 that I decided enough was enough. I’d been getting plagued with requests for feedback every time I made an online purchase or had an interaction with an organisation; so, I decided I wouldn’t do feedback anymore. It’s been liberating. However, that’s not so say I haven’t wanted to speak my mind occassionally – especially when I’ve had a bad experience, and I’ve had a few of those recently; but in those circumstances I lodge a complaint. Unfortunately, complaints can be hard work, and even the way the complaint is handled is sometimes itself worthy of a complaint. Perhaps its about time that organisations stopped plaguing us with feedback requests, and started to really examine their interactions with customers. At the moment every organisation seems to be ploughing money into using AI to create so-called intelligent Chat Bots (which I have found to be useless so far). A more productive approach might be to use AI to examine every interaction they have with customers – verbal and written combined with process statistics about delivery times etc.. The AI would be able to deduce from tone, language and performance whether or not a customer was satisfied or not. The more proactive managements might even be able to use this intelligence to step in and deal with problems as they are happening, rather than just trying to improve processes and training retrospectively.

Author Archives: admin

A Lack of Laces

I’ve had trainers that I really liked, but the laces frayed before the trainers wore out. I went back to the retailer to get replacement laces, but they didn’t have any that were an exact match. You see, trainers today come as a complete package: both functional and designer – and with a pair of laces that do one and big-up the other. Getting replacement laces is very, very difficult. I’ve never managed it. Yet this could be a money maker for the suppliers and an insurance for the purchaser. If I’d been offered spare pairs of laces for the trainers I was buying, I would have bought at least one pair – maybe two. It could be a nice little earner for the retailer; the buyer would be a happier bunny; and, maybe, there’d be fewer trainers in landfill.

An iPad Combination

Having acquired a new iPad, I needed to transfer all my digital object collections from old to new tablet, so I decided to take the opportunity to explore the issues associated with a combined set of collections. I’m using the iPad Sidebooks app which provides a hierarchical bookshelf interface. A set of objects sits on a bookshelf. Each object can be either a single file or can represent a lower-level bookshelf containing either single files and/or objects representing even lower-level bookshelves. The Sidebooks app does display objects in an attractive visual way, and the iPad is a very portable and easy to open up and use in any setting. However, that doesn’t mean to say that it is necessarily the best place to combine collections. The following shortcomings need to be understood from the outset:

- Sidebooks can display digital objects, but many of the collections have objects which are only in physical form, for example, the stamp collection.

- Sidebooks is not the primary storage location for any of these collections (for digital items it is the laptop; and the physical items are located in a variety of places), so there is a danger of the Sidebooks version getting out of synch with the original.

- Some collections loaded into Sidebooks may be broken down into a limited number of named subsets for ease of comprehensibility and access, but the files in the original collection are not sub-divided in that way.

- For some collections (such as Mementos) only a subset of the objects is downloaded into Sidebooks; those items not in named subsets are simply not present.

Having said all that, the exercise to transfer a range of collection objects into the new iPad did provide an opportunity to think about the practicalities of Combining Collections. Actually, the word ‘transfer’ is not strictly correct; in fact, I just used the material on my old iPad as input to what needed to be loaded into the new iPad. Other inputs included the journeys I’ve recorded in this web site; and my awareness of other collections that I have. This examination surfaced the first issue associated with combining collections – Content. In some cases, it was difficult to decide whether to include a collection or not because of the personal nature of the material (poetry written in my younger years for example), and because the new iPad might be looked at by family members or by those inheriting when I die. I also experienced issues with the Mementos collection because it has hundreds of files distinguished only by facets in the index. To just include every memento file in Sidebooks would present the user with an amorphous mass. Instead, I wanted to have named subsets of material like the companies I worked for or the places I lived. However, this meant choosing a limited number of named subsets – and leaving out the remaining files.

Having decided what collections to include, I was now ready to start loading objects into the new iPad; but was immediately faced with Presentation issues: I know from my experience with my old iPad, that the top level in Sidebooks can look extremely cluttered making it difficult to grasp the totality of what is being represented – even if you are the owner and are familiar with the material. For other people – family or those inheriting collections – it must be an even bigger problem – see below.

Of course, it might just be the app. There are many other similar applications out there and they might do a better job. I shall certainly be looking into that in the later stages of this journey; and, of course, it may simply be better to combine the collections in the place they are currently stored – the laptop. However, for this exercise of moving to a new iPad, I’m sticking with Sidebooks; so, I needed to find a way to present the combined set of collections in a clearer way.

Of course, it might just be the app. There are many other similar applications out there and they might do a better job. I shall certainly be looking into that in the later stages of this journey; and, of course, it may simply be better to combine the collections in the place they are currently stored – the laptop. However, for this exercise of moving to a new iPad, I’m sticking with Sidebooks; so, I needed to find a way to present the combined set of collections in a clearer way.

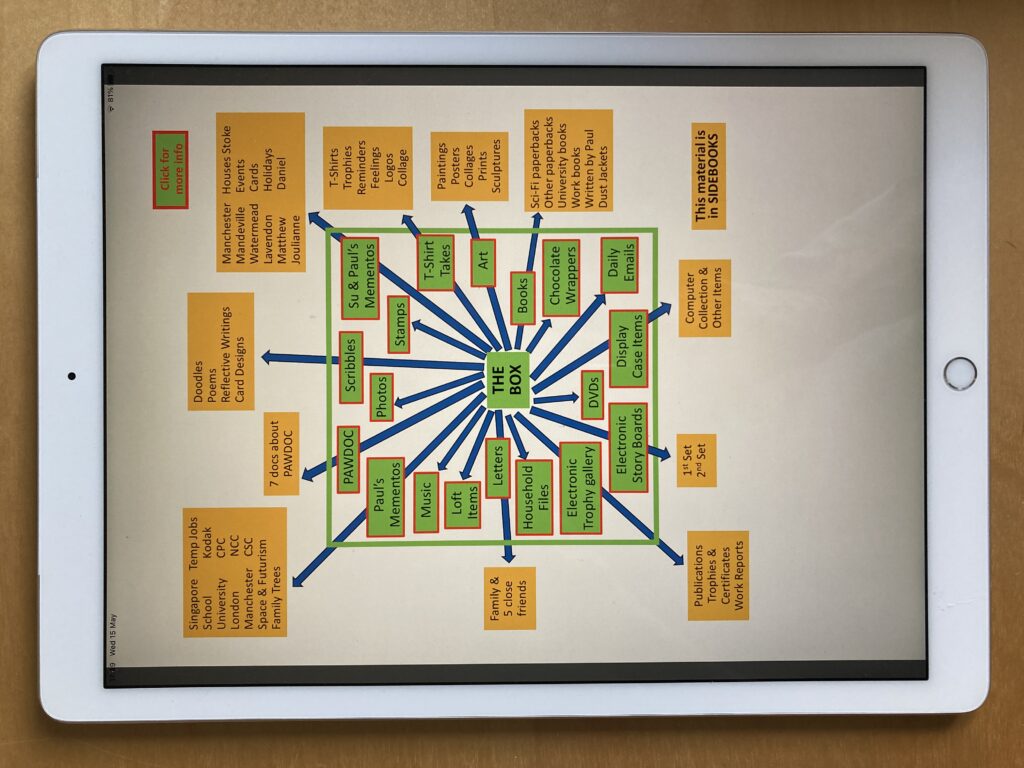

The solution I came up with was a PDF document with all the collections shown on the front page and with links to descriptions of each collection in the body of the document. This sits at the top level In Sidebooks with the front page showing. At the same level in Sidebooks are icons representing the bookshelves which contain substantive objects at lower levels in the hierarchy.

The PDF document also enables information to be included about the collections which are not suitable for including in Sidebooks such as the Stamp collection (I was able to include a list of the countries being collected and their status). I believe the PDF diagram makes things clearer – but it’ll be interesting to see if I have the same view several months down-stream.

The PDF document also enables information to be included about the collections which are not suitable for including in Sidebooks such as the Stamp collection (I was able to include a list of the countries being collected and their status). I believe the PDF diagram makes things clearer – but it’ll be interesting to see if I have the same view several months down-stream.

There was another reason for creating a front-end diagram of all the collections: to cater for the needs of other people (such as family, or those who inherit) who might encounter the material. It seems to me that there are three main characteristics which need to be catered for: first, people easily become overwhelmed and turned-off by large quantities of unfamiliar and apparently disorganised things; second, many people are just simply not interested in some of things that we ourselves are interested in; and finally, people will always want what they have not got; but once they have those things, while wanting to still have them, they lose a lot of interest in them. All three characteristics may affect how people feel about a combined set of collections. Therefore, I have chosen to call the PDF document ‘THE BOX’, and to list all the different collections in the box on the front page of the PDF, in an attempt to inspire interest, and to avoid overwhelming people (though I’m not sure this latter requirement has been achieved…) – see below.

The descriptive information within the PDF enables people who aren’t really interested in the named topic to get a quick idea of what’s in the collection without being overwhelmed by the objects themselves, thereby perhaps wetting their appetites to find out more; and once people become familiar with the contents of THE BOX, it may provide them with the confidence of knowing where the things they treasure are located. The idea is that THE BOX is full of unknown and interesting things and provides a quick way of finding out a bit more, and of documenting clearly what is where. Whether THE BOX succeeds in doing this is again something I may have more views on in a few months’ time.

With the rough design of THE BOX established, I started to load in the various digital objects associated with each collection. This is when I started to find other Content issues. In some cases, I had to make decisions about whether to include or exclude particular objects; for example, in my collection of Scribbles (Doodles, Reflective Writings, Poems etc) I decided to exclude school essays, but included designs for cards I made for particular people/occassions. In other instances, I revised how things were named and organised; for example, what was in the old iPad as a single set of ‘Paintings and Posters’ became a set named ‘Art’ subdivided into ‘Paintings & Drawings’, ‘Collages’, ‘Prints’, ‘Posters’, and ‘Sculptures’.

Another content-related issue was where an object can appear logically in two or more collections; for example, “The Meteor” – a book I self-published about parts of my stamp collection – can logically appear within both the ‘Stamp’ collection and the ‘Books I have written’ collection. This is an issue I had previously encountered in the Electronic Story Board journey, and is an inevitability with large collections of material. For small numbers of digital objects there is a simple solution: simply place a copy of the object concerned in both places. For larger numbers of digital objects, it may be best to provide links to the master version of the object concerned. The former is the only feasible solution in Sidebooks.

As I continued to load more collections into Sidebooks, I encountered a number of instances in which the Technical constraints of the Sidebooks app affected what could be included in the overall combined collection. Sidebooks only supports PDF files, so if large numbers of objects in a collection are stored in another format – Word or jpg for example, a large amount of effort would be required to convert them all into PDF to display them in Sidebooks. In the case of very wide spreadsheets even converting them to PDF wouldn’t work well because the conversion process would create page breaks across the width of the spreadsheet resulting in a PDF consisting of a series of rather disjointed pages. Hence, such technical issues create practical issues affecting what can be combined in a single overall space. Obviously, the more consistency that exists between the way the objects in a particular collection are constructed, and the technical requirements of the application which is to display all the collections, the easier it is going to be to create the combined collection. A prime example of this is when individual objects are given informative file titles, but it is subsequently decided to combine multiple individual files into a single PDF file to meet Sidebook’s requirements, for example. In this circumstance it is likely that much of the file title information will be lost.

The final issue I encountered was specifically to do with Physicality: some collections were simply not in a state to include in an overall digital combined collection. For example, the stamp collection consists of 19 physical albums. To digitise them would not only be too onerous, but the result would be out of date as new items get added. For these types of collections, THE BOX provides a perfect compromise in which some information can be provided without having to load in the actual objects themselves.

In summary, the main issues I encountered when trying to re-assemble a combined collection on the iPad, are to do with Content, Presentation, Technology, and Physicality. These are the topics that I shall pay considerable attention to when undertaking the next phase of this journey. And, for the record, the statistics associated with this initial attempt at an overall combined collection are: 19 separate collections of which 11 have objects in Sidebooks consisting of 2478 separate files taking up 22.6 Gb of storage.

A Search for Collection Commonalities

Over the years I’ve organised a wide variety of collections – many of them documented in this web site. Each one has had its own special challenges and solutions. However, I’ve also noticed the following types of commonalities between the collections and the way I’ve dealt with them:

- Relationships between objects: for example, between a Supertramp album digitised for the Music collection, and a ticket to a 1972 Supertramp concert in the Memento collection

- Indexes: for example, the index for my own personal Memento collection from before I was married, has exactly the same fields as the index to the separate collection of Mementos belonging to my wife and myself.

- Searching: as a result of the worldwide take up of internet search engines such as Google, search these days is invariably done by specifying keywords and phrases, regardless of the way the information being searched is structured. For example, The Photo collection has an index of each set off photos (mapping onto the old-style films that were inserted in cameras and developed) which can be searched for things like particular holiday destinations or photos from a particular year; however, the Trophy collection has no index and instead just has files with extensive descriptive information within the file titles which can be searched using the windows File Explorer Search bar.

- Display and access – physical objects: for example, the Book collection is on display in bookcases, and the memento collection is on display in boxes and folders on a shelf in a tallboy.

- Display and access – digital collections: for example, both the University Books collection and some of the Letter collection are in the Sidebooks app on the iPad.

- Storage – physical objects: for example, those objects in the Computer Artefact collection that are not in the display cabinet are stored in containers in the loft; and the family memento collection is stored in folders in a chest in a downstairs room.

- Storage – digital objects: for example, the Photo Collection’s digital files and the PAWDOC digital document collection are both stored in Window’s folders.

- Passing on collections: for example, in the case of both the Physical Memento collection and the Stamp collection I was uncertain if younger members of the family would want to inherit them and consequently took steps to mitigate the problem (for the Memento collection I created a Wish Table which identified those items which were important for family history and those which could be disposed of without concern; and for the stamp collection I digitised the stamp pages and created two copies of a hardcopy book – one for each grandchild).

Such commonalities have led me to believe there may be some merit in a detailed examination of each collection with a view to identifying if there are:

- Better ways of doing things for an individual collection

- Standardised ways of doing things across collections

- Collections that might be usefully combined together in some way

- Particular technologies that might be applied across collections.

As I’ve been thinking about how to undertake this journey, I’ve acquired an iPad Pro to replace the old iPad Air in which many of my digital objects reside in the Sidebooks app; so, I already have a data migration job to perform. Therefore, I’ve decided I’ll use the opportunity to examine ALL of my collections to re-assess what should appear in Sidebooks and how they should be ordered and arranged. This exercise will provide me with an opportunity to document all my collections and to take a partial look at the commonality questions.

With those learnings under my belt, I intend to take this journey forward with a detailed overall look at two separate sets of collections. First, collections belonging to my mother who is now residing in a home and who has entrusted most of her personal belongings to me; and secondly, all my own collections. I’m hoping that these two disparate sets of material will be sufficiently diverse to produce some generalisable conclusions.

Turning a Stamp Album into a Book

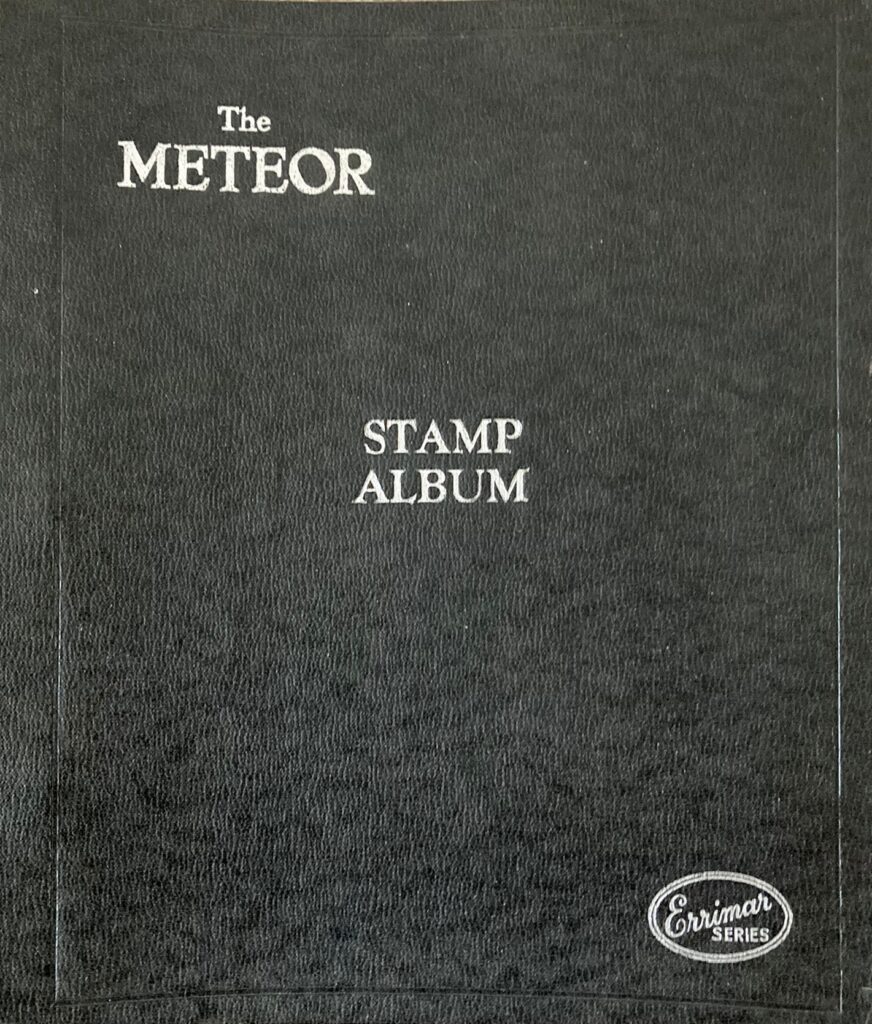

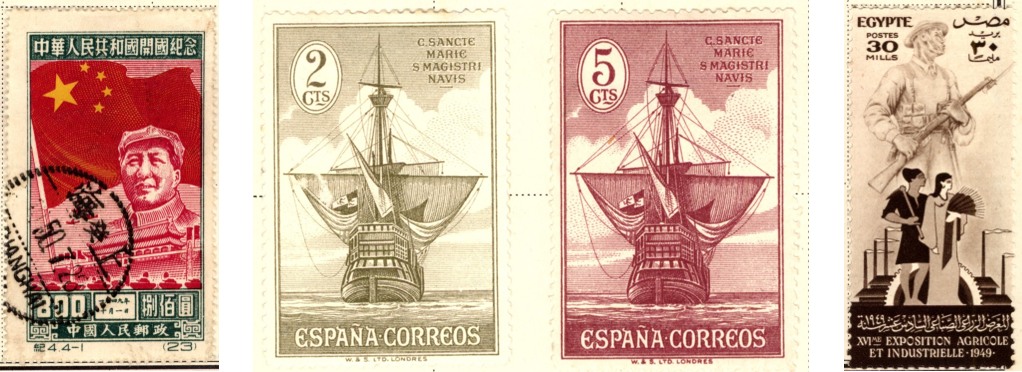

It was in the lounge of our house in Singapore in the 1950s that my father took me through some of the pages of his album. I was about 7 or 8, and it’s my earliest recollection of stamps. Some big ones made particular impressions – two portraying Spanish Galleons, one of a long grey one of a man, and a red one with a star.

A few years later I started collecting stamps myself. I wasn’t an avid collector, but the various accoutrements of my collection – albums (stick-in and stock books), tweezers, country envelopes, tatty envelopes full of stamps on paper waiting to be soaked off – had always been with me from those early days. It was something I did from time to time – a tactile and gentle pursuit – as had hundreds of thousands of like-minded collectors for well over a hundred years.

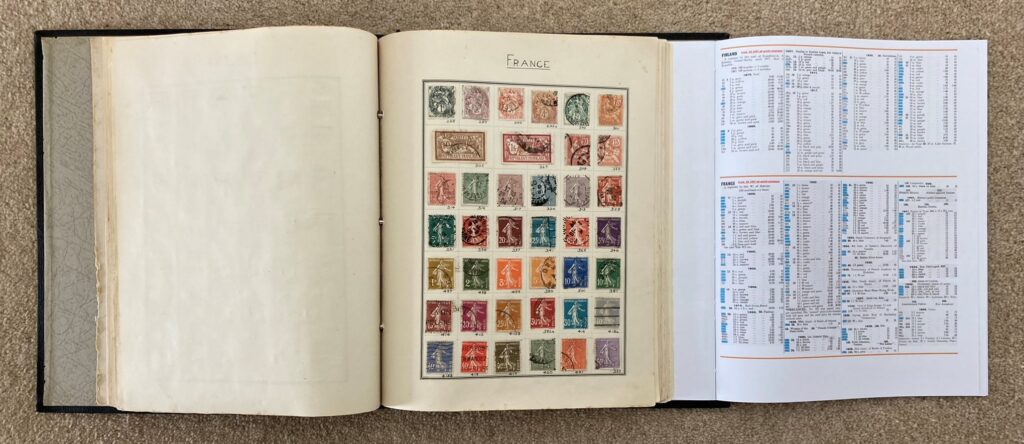

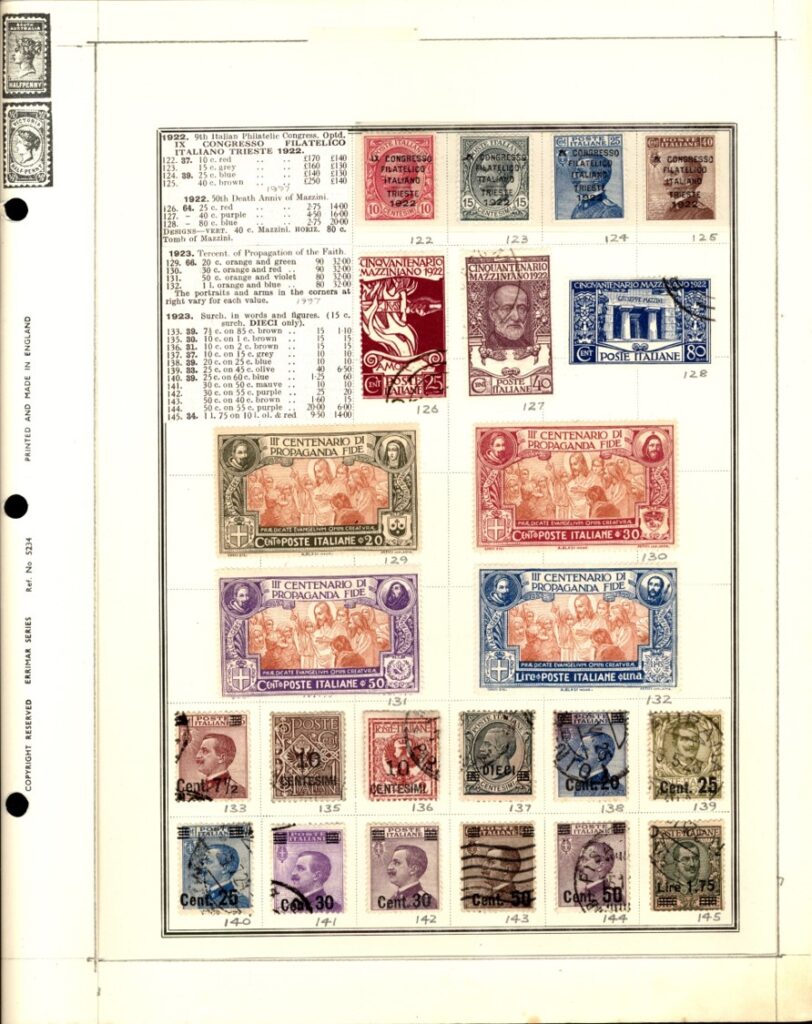

Sometime in the 1990s, when my father was getting on a bit, he gave me his stamp albums – including that one he had showed me in the lounge in Singapore all those years ago. I didn’t do much with that Meteor album for several years; but, as retirement approached in 2012, a germ of an idea started to formulate. The album wasn’t full by any means but it did contain a substantial number of stamps across about 30 countries. My father had always produced beautiful handwriting, and he had written the name of the relevant country in black ink and capital letters at the top of each page as in the example below.

I decided I would discard pages without a country name and would try and completely fill all the pages that remained in the album, unconstrained by date order, or whole or part sets, or whether they were mint or used; but guided by the eras of the existing stamps. I made one exception to this goal: Italy was particularly well endowed with stamps, so I decided to use the spare untitled pages to collect all Italian stamps produced up to 1980 as defined in the 1997 Stanley Gibbons Simplified Catalogue. I perhaps didn’t quite realise at the time how ambitious this might be, though, in my defence, I may have casually thought that it wouldn’t matter if some of the more expensive items were simply missed out (a seriously unrealistic misjudgement….). Anyway, once full, the album would then become a kind of memorial of my father and his stamp collecting and his immaculate writing. I could round it off with a page at the beginning describing how he collected stamps and inspired me to do so, and including some photos of him at various stages of his life.

I decided I would discard pages without a country name and would try and completely fill all the pages that remained in the album, unconstrained by date order, or whole or part sets, or whether they were mint or used; but guided by the eras of the existing stamps. I made one exception to this goal: Italy was particularly well endowed with stamps, so I decided to use the spare untitled pages to collect all Italian stamps produced up to 1980 as defined in the 1997 Stanley Gibbons Simplified Catalogue. I perhaps didn’t quite realise at the time how ambitious this might be, though, in my defence, I may have casually thought that it wouldn’t matter if some of the more expensive items were simply missed out (a seriously unrealistic misjudgement….). Anyway, once full, the album would then become a kind of memorial of my father and his stamp collecting and his immaculate writing. I could round it off with a page at the beginning describing how he collected stamps and inspired me to do so, and including some photos of him at various stages of his life.

I duly gathered together the pages with country headings, moved stamps on untitled pages, and set about finding stamps to fill the gaps. Having this goal inspired me to attend stamp fairs, and to start buying auction lots; and by about 2017 I’d completed 14 of the 33 countries; but I was starting to realise that it was going to be a big – and expensive – job to acquire the whole of Italy up to 1980.

It was also in 2017 that my second grandchild was born and I was beginning to wonder whether I, like my father, would be able to pass on my stamp collection to one or both of them. I knew that none of my own children were in the slightest bit interested in stamps; so, the grandchildren were probably the last port of call. However, there could be no guarantee that they would be interested either; and, in any case, what would happen if they both became collectors? How could I choose which one to give their great-grandfather’s album to? I ruminated on this conundrum as I continued to add to the album.

Sometime during the following few years, I decided to augment the burgeoning album with the catalogue entries for the stamps it contained (something I’d already done successfully in my Great Britain album by simply cutting out the relevant parts of pages from the ‘Collect British Stamps’ catalogue). I reasoned that the information associated with the issuance of stamps – whether to commemorate a person or event, or to indicate what reign of a monarch it took place in – was not only useful to manage the collection, but also interesting, perhaps even educational, even for those not generally interested in stamp collecting; and that the relative values of different stamps attest to the scarcity and desirability of the more valuable items. All this information would surely make the album that much more interesting to its potential future owners. To enable the reader to match a stamp to its catalogue entry would simply require that the relevant catalogue number was written next to each stamp.

I started with the Italian collection and placed cut-outs or photocopies of the relevant catalogue entries onto the relevant pages.

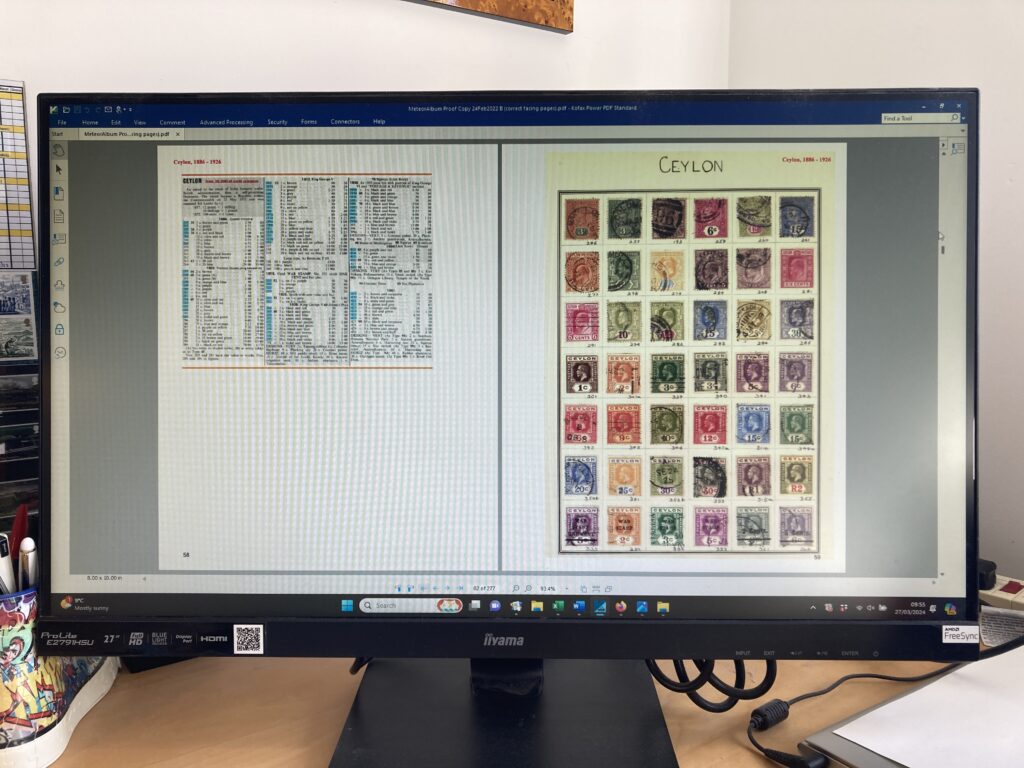

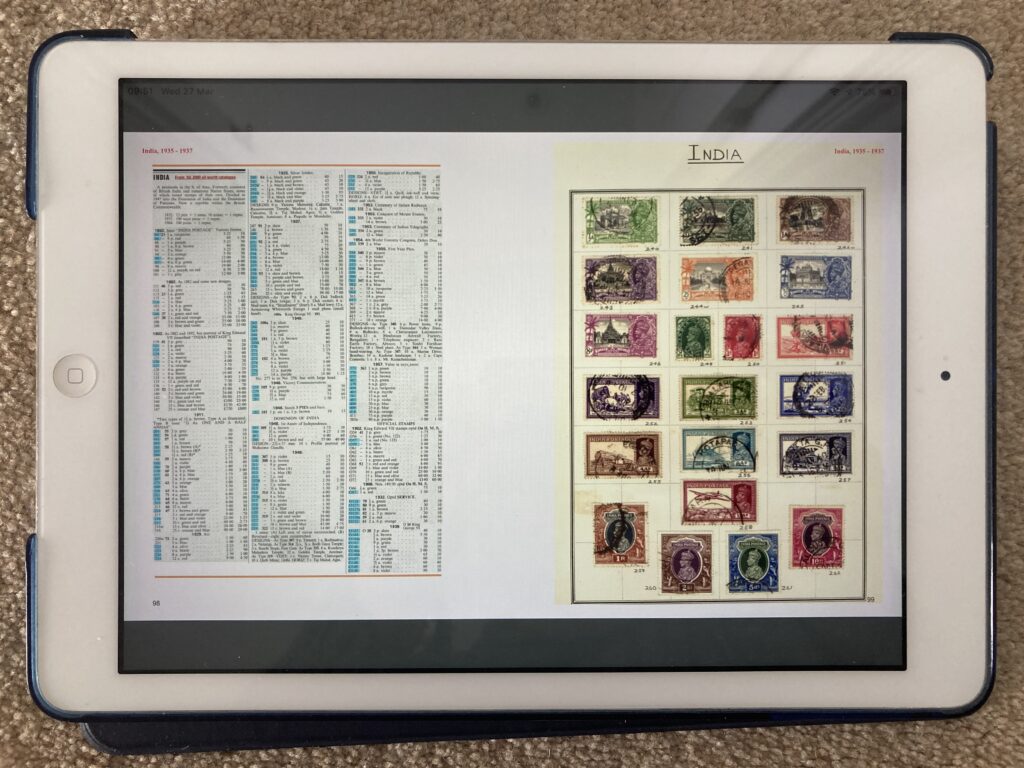

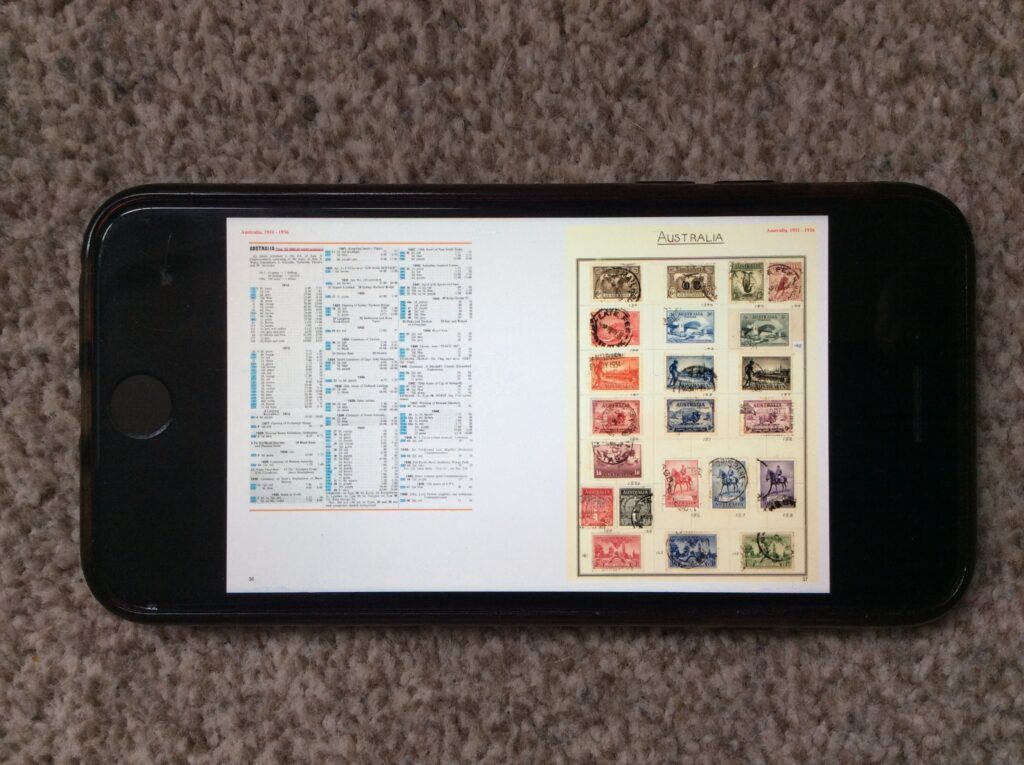

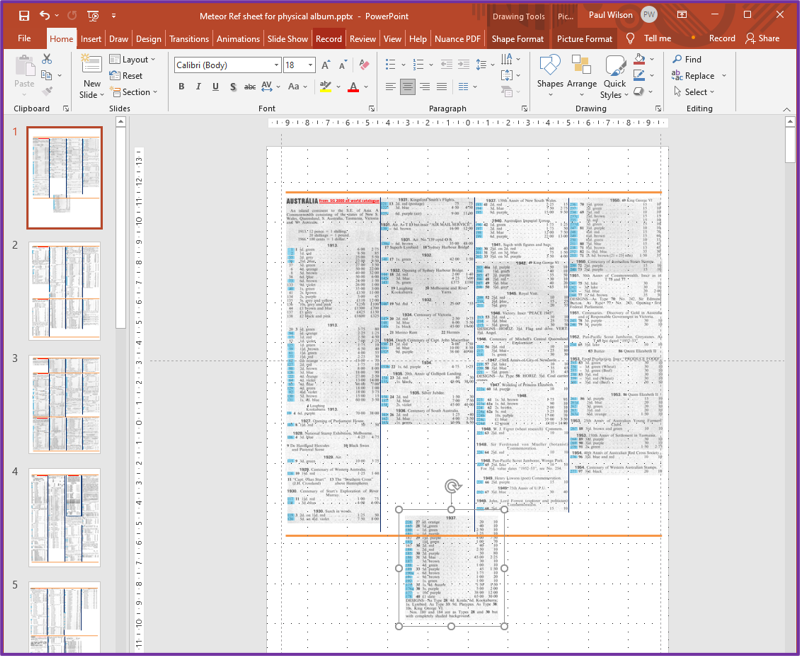

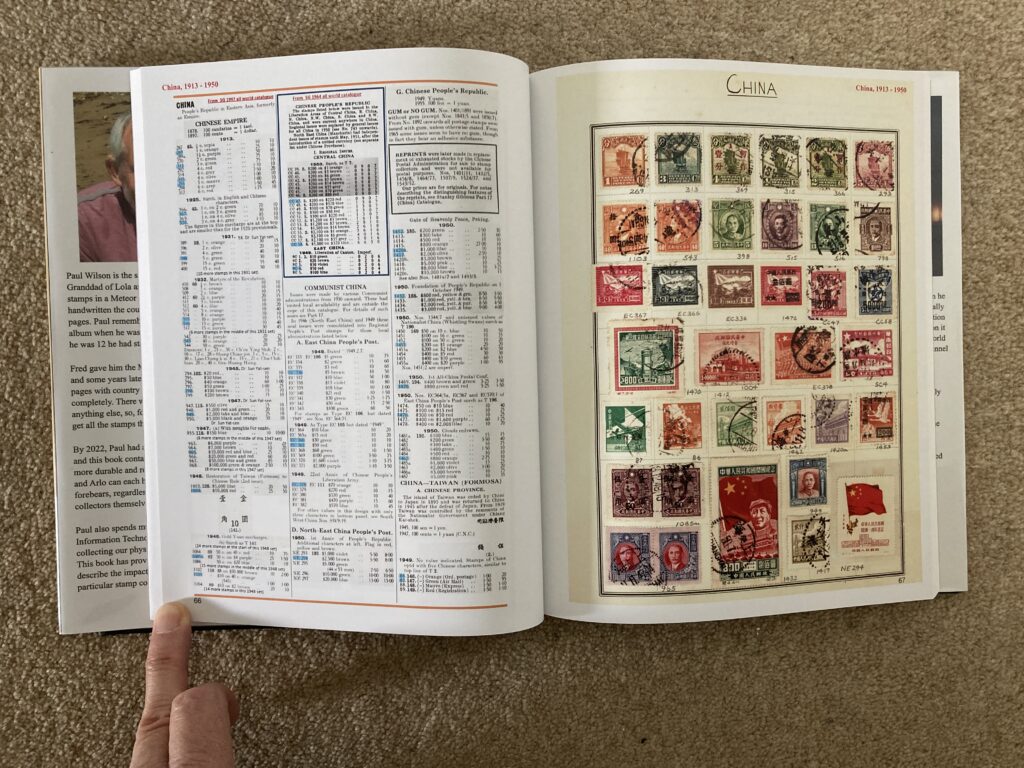

When it came to the other countries, though, I realised this wouldn’t work because, not being constrained to stamps from consecutive dates or sets, meant that there was just too extensive a range of catalogue entries to include. So, for those pages, I elected to scan the relevant catalogue pages and to cut and paste the entries relevant to a particular album page onto a single page using the PowerPoint software package (the blue highlights in the example below indicate which stamps are included in the album).

When it came to the other countries, though, I realised this wouldn’t work because, not being constrained to stamps from consecutive dates or sets, meant that there was just too extensive a range of catalogue entries to include. So, for those pages, I elected to scan the relevant catalogue pages and to cut and paste the entries relevant to a particular album page onto a single page using the PowerPoint software package (the blue highlights in the example below indicate which stamps are included in the album).

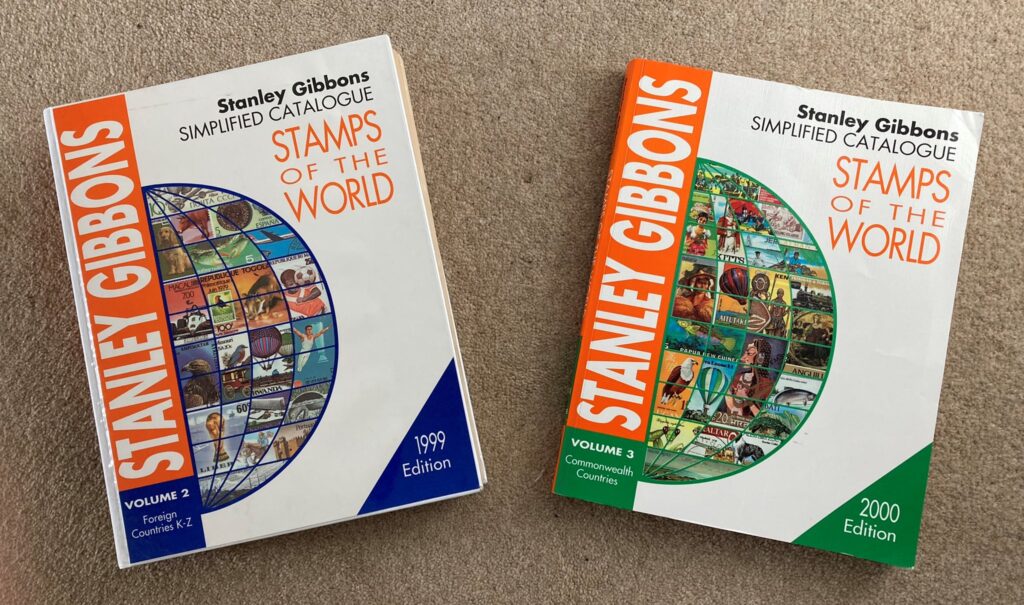

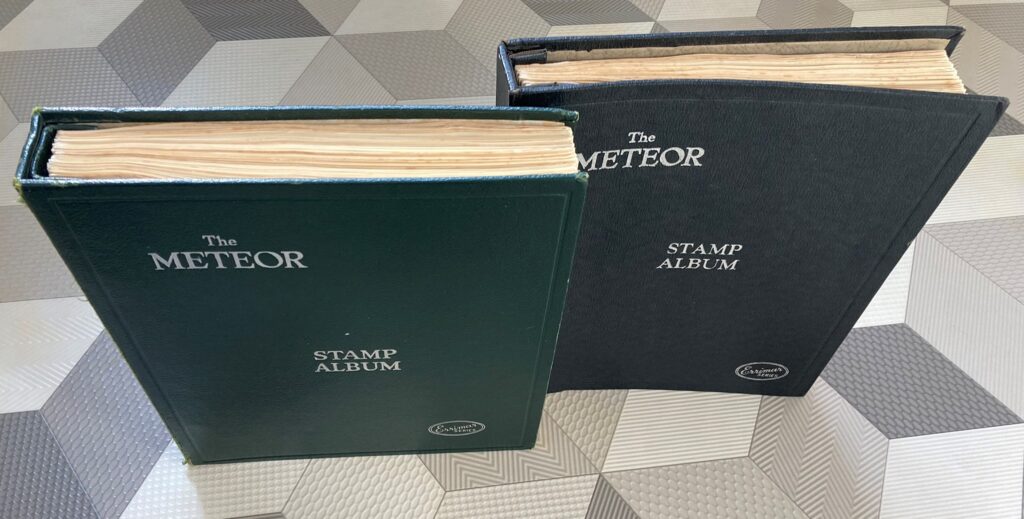

My plan was to print these pages out and to attach them to the inside back cover of the album so that the relevant page could be turned out to the right of the album and be visible when a particular album page was being looked at. I was confident that I could achieve this at the bookbinding classes I’d been attending for 5 years or so. I duly acquired two old 1999 and 2000 Simplified Catalogues for the non-Italian countries for about a fiver each on ebay (shown below) and set about assembling the catalogue entries for each country and labelling each stamp in the album.

My plan was to print these pages out and to attach them to the inside back cover of the album so that the relevant page could be turned out to the right of the album and be visible when a particular album page was being looked at. I was confident that I could achieve this at the bookbinding classes I’d been attending for 5 years or so. I duly acquired two old 1999 and 2000 Simplified Catalogues for the non-Italian countries for about a fiver each on ebay (shown below) and set about assembling the catalogue entries for each country and labelling each stamp in the album.

In 2020, I had won an auction lot of a single album dedicated to Italian stamps including many of the more valuable earlier items. This made substantial inroads into my Italian Wants list. It had cost me £380 – about double the amount I usually invested in an auction lot; but, after removing the stamps I needed, I was able to break up the contents and sell them for around £200 overall – an excellent defrayment of the original cost.

2020 was also the year I decided I would self-publish a book about my IT experiences over the previous 50 years, using an internet-based company called Blurb. The resulting 8×10 inch hardback with 440 glossy pages, lots of colour photos and images, and a glossy, full colour, wrap-around dust jacket initiated another germ of an idea. I realised that I could scan the pages of the filled Meteor album and include them in a Blurb-produced book. I could have two copies of the book produced, so that I could give one to each grandchild at some point. It wouldn’t matter if they marked or tore them, or damaged them in any way, as the digital version would always be available to produce new copies if necessary. There would be no concerns about damaging or losing valuable stamps, or of the album being sold off by young adults eager to release funds (a possibility perceived by my own youthful short-sightedness); and I could have a copy myself, secure in the knowledge that, if my collection was stolen at any time, or destroyed in a fire or random act of god, I would still have the book to look at and enjoy.

With these ideas firmed up and cemented in my mind, I set out with renewed vigour to complete the non-Italian countries, and to start acquiring the more expensive Italian stamps (by that point I’d decided it had to be ALL the Italian stamps to 1980). Ebay was my main source for this material, though I did get some stamps from eBid and Hipstamp. Using all these sites, I soon completed all but two of the non-Italian countries, and started to home in on the remaining Italian wants. It soon became apparent to me that the more expensive stamps could be purchased for a wide range of prices. This was partly due to varying quality but was also related to how quickly individuals or dealers wanted to realise their cash. I started to scour eBay regularly looking for bargain ‘Buy-it-Nows’ or low starting prices. I eventually came across Kilowareman – an unusual operation based in the Netherlands which appeared to have an unlimited supply of ex-dealer’s stock and which published dozens of new lots on ebay every day with a standard starting price of 1 Euro regardless of value, including many of the Italian stamps I wanted. I bought several of the high value stamps I needed from Kilowareman, and was never disappointed; despite a standard £1.50 postage cost to anywhere in Europe, they always arrived safely about a week after the auction in a cellophane packet attached to a page inscribed ‘greetings from Kilowareman’ inside a simple envelope. On one extraordinary occasion I won a lot of 7 overprinted stamps with a catalogue value of several thousand pounds (at 2020 values) with a bid of £54 which I submitted in the last few seconds of the auction while having a post-competition lunch at a golf club.

Common sense would say that they must be fakes – but they didn’t look any different from the real thing and I wasn’t going to start detailed investigations to determine if they were genuine or not. They would look fine in my father’s album; and, in any case, I reasoned that, if KIlowareman was selling bulk lots of ex-dealer’s stocks, then the original dealers would have had to be taken in as well or simply not have marked the items as of doubtful provenance – which was possible but perhaps a little unlikely. Well, that was my rationale for happily paying far less than catalogue value for the more expensive stamps.

Common sense would say that they must be fakes – but they didn’t look any different from the real thing and I wasn’t going to start detailed investigations to determine if they were genuine or not. They would look fine in my father’s album; and, in any case, I reasoned that, if KIlowareman was selling bulk lots of ex-dealer’s stocks, then the original dealers would have had to be taken in as well or simply not have marked the items as of doubtful provenance – which was possible but perhaps a little unlikely. Well, that was my rationale for happily paying far less than catalogue value for the more expensive stamps.

By early 2022, I was very close to completing the whole collection with just 3 Italian stamps to get. One of the Italian stamps was specified as a 10 cent stamp in the Stanley Gibbons Simplified album, however, all my trawlings and investigations led me to believe it was a 40 cent stamp (which I did have). So, I emailed the Stanley Gibbons Catalogue Department and asked if this was the case. On 19th January I received the answer – it was indeed a long-standing misprint – reminding me that you can never be absolutely sure that anything in print or on the internet is correct: reader beware!

On the same day I bought one of the other two outstanding items in HipStamp, leaving me with a last remaining gap for PL650, a 30 cent blue Italian Parcel Post stamp from 1945. Not the most expensive Italian stamp according to Stanley Gibbons (£39 mint, £31 used), but the most elusive in my experience. I finally found it a week later by searching an Italian Dealer’s items on eBay using the Italian word for parcel – ‘pacchi’. I’d missed this previously because, for some unknown reason, searches using the English equivalent, ‘parcel’, didn’t produce any hits – despite the word parcel being displayed in the title of the lot – ‘1945 Lieutenancy Parcel Post 30 Cent MNH’. However, all became clear when I got confirmation of my order from ebay: The actual title was, ‘1945 LUOGOTENENZA PACCHI POSTALI 60 CENT MNH’, and the title I’d been shown must have been an automatic translation which was not used in the search algorithm. It was a timely reminder that internet searching is not an exact science, and that some thought and perseverance may be required to find what you want.

By this time, I had started to explore how I would construct the book using Blurb’s BookWright software. I decided that there were too many stamps to include in a single album, so I bought another album just like the one my father had given me, on eBay. I then had one album for the Italian stamps and one for all the other countries.

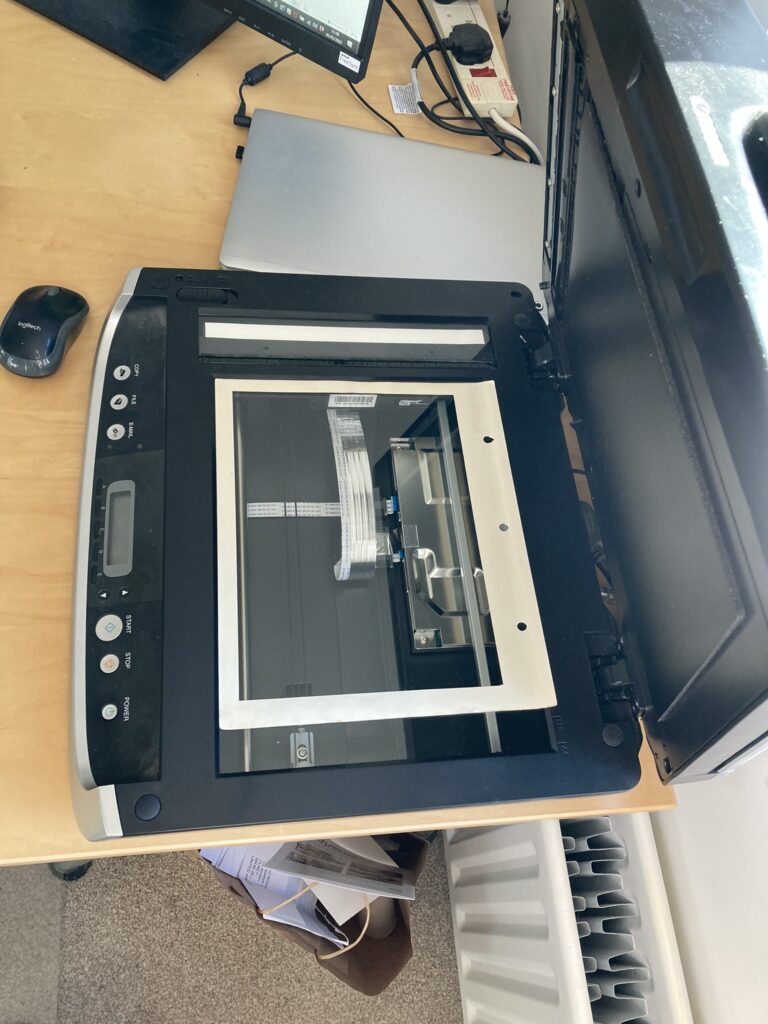

Next, I turned to the practicalities of assembling the album pages in Blurb’s publishing programme – particularly the following:

Next, I turned to the practicalities of assembling the album pages in Blurb’s publishing programme – particularly the following:

- Ensuring the stamps would be reproduced in actual size: The scan of a whole album page was too big for the book page, so when importing the scan to a Blurb page the system automatically resized it to fit thereby producing smaller than actual sizes of the stamps. To avoid this, I needed to crop the image before importing it; so, I created an overlay which lay on the scanner platen and on which the album page was layed.

The outline of the overlay in the resulting scan was where the image would be cropped. Using this approach, and after some trial and error, I got the sizes of the stamps in the imported images in the book to be pretty much actual size.

The outline of the overlay in the resulting scan was where the image would be cropped. Using this approach, and after some trial and error, I got the sizes of the stamps in the imported images in the book to be pretty much actual size. - Getting the composite catalogue pages in shape: The four-column format I’d used to construct the composite catalogue pages for each country was based on them fitting into the back of the meteor album. However, as I’d already discovered with the album pages, the Blurb book pages were smaller, and I realised I would have to rejig the country catalogue pages to a three-column format. This wasn’t too difficult using Powerpoint, and I exported the resulting images in png format ready for inclusion in the book. There was one issue – Blurb alerts warned me that the resolution of these images were ‘lower than that which Blurb recommends for great print quality’. This despite me scanning the catalogue pages at a very high resolution. I think resolution deteriorated through the various stages of cutting and pasting elements of the overall page. Anyway, they were readable when I printed them out from PowerPoint, so I hoped they’d still be readable in the Blurb book, and indeed it turned out that they were.

- Positions, sizes and colours of page numbers and running headers: I decided to provide a standard header on each page consisting of country name and date range of the stamps on the page, for example, ‘Ceylon, 1886 – 1926’. These would be placed in bold red 10 pt Times New Roman font at the top of each page, on the left side of the left-hand pages and on the right side of the right-hand pages. For page numbers, I used the standard Blurb function to place them in similar positions to the headers but at the bottom of the page, using bold black 10 pt Arial font. I realised that some of the page numbers might be obscured by the black surround of some album pages – but decided I would deal with that once I’d got everything in place.

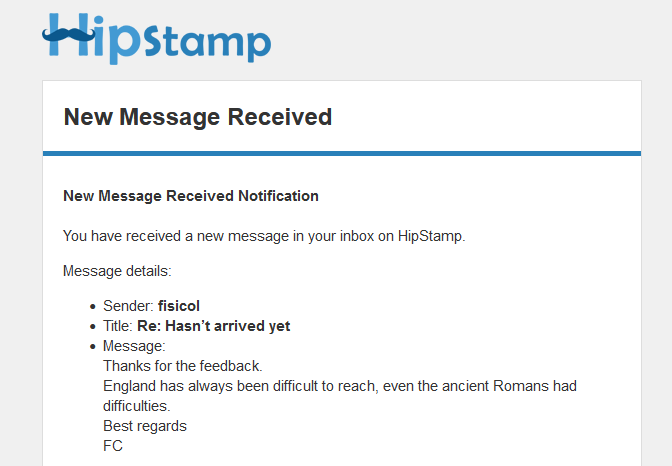

With all these preparations complete, I started assembling the contents of the book on the 1st February. It took roughly 100 hours over a 17-day period to scan all 169 album pages, check all the catalogue images against each scanned album page, and to insert both album page scan and relevant catalogue image into the BookWright application. Conveniently, the last stamp I was waiting for to complete the album arrived on the penultimate day of scanning after a 30-day journey from Italy. I had been waiting for it for three weeks before messaging the vendor, Fisicol (an Italian dealer using the Hipstamp site), asking when I could expect it, and he advised that it often took three or four weeks; and sure enough it arrived a week later. Shortly after setting the status to ‘Received’ and providing feedback, I received the following memorable message from Fisical:

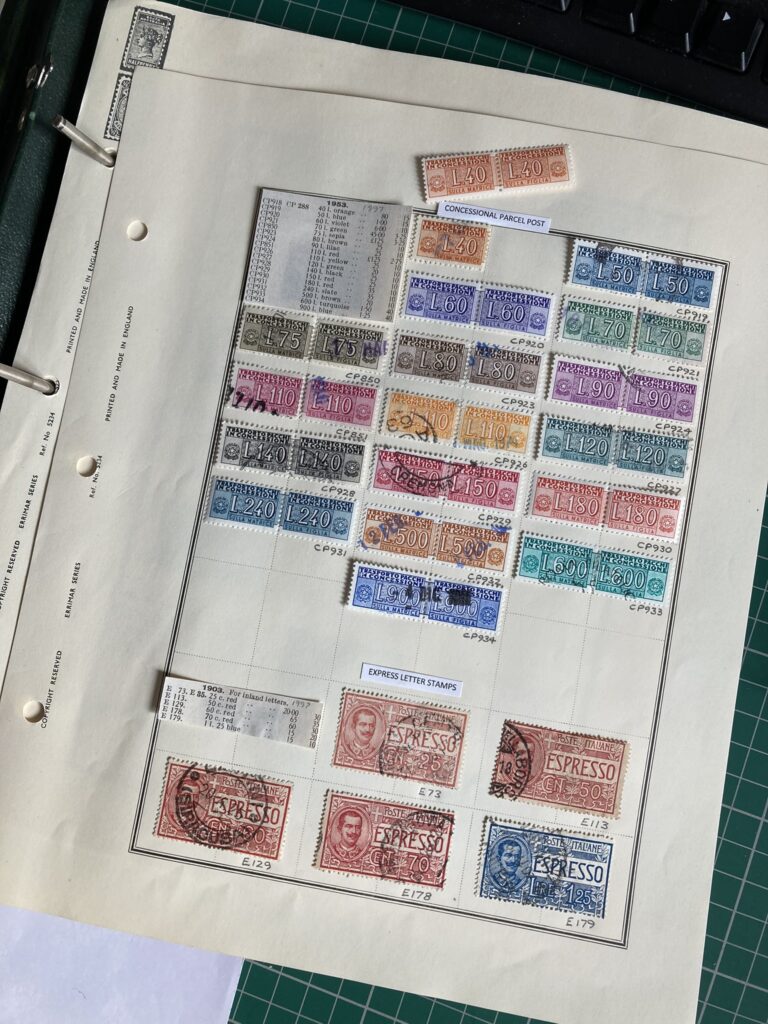

I duly placed this, the last of the two thousand and forty seven Italian stamps, with some sense of achievement, into the Concessional Parcel Post section of the Italian collection, replacing the single left-hand version for which I had been unable to obtain a right-hand partner. The whole collection totalled 4084 stamps dated between 1860 and 1980, from 33 countries.

I duly placed this, the last of the two thousand and forty seven Italian stamps, with some sense of achievement, into the Concessional Parcel Post section of the Italian collection, replacing the single left-hand version for which I had been unable to obtain a right-hand partner. The whole collection totalled 4084 stamps dated between 1860 and 1980, from 33 countries.

After some final tidying and checking of the whole volume in Bookwright, I sent the book for printing at a cost of £81 a copy. I now have three copies of a beautiful, glossy, 274-page, book containing an introduction and both albums – one for myself and one set aside for each for my two grandchildren which I shall give them when they are a little bit older.

After some final tidying and checking of the whole volume in Bookwright, I sent the book for printing at a cost of £81 a copy. I now have three copies of a beautiful, glossy, 274-page, book containing an introduction and both albums – one for myself and one set aside for each for my two grandchildren which I shall give them when they are a little bit older.

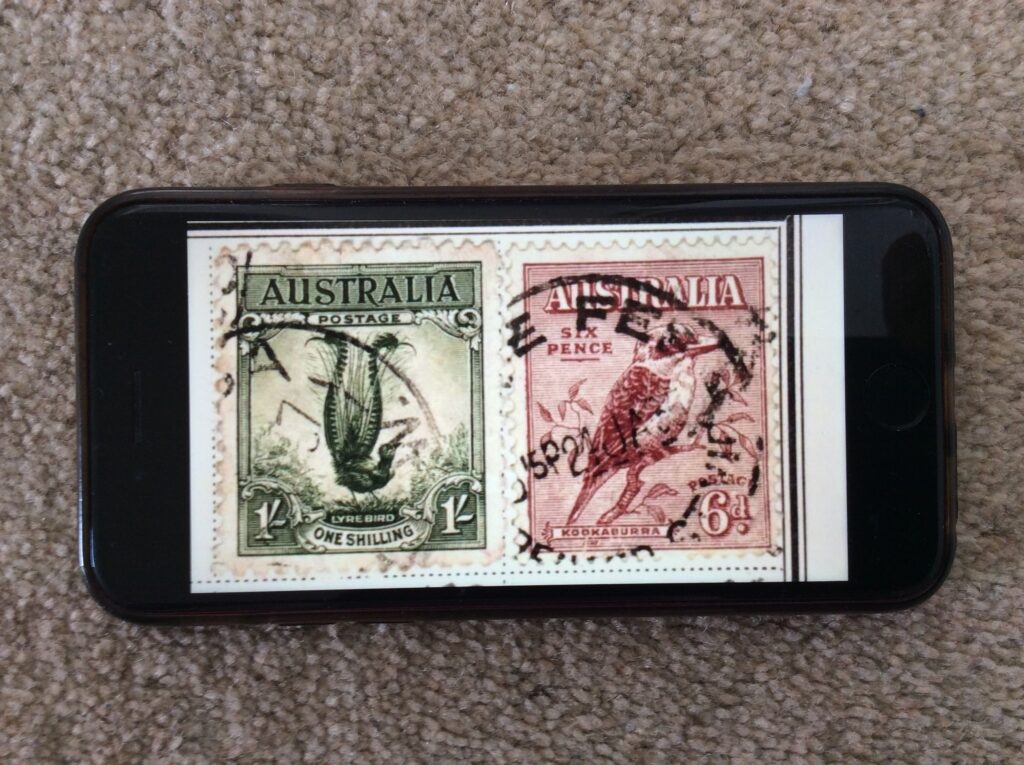

I also have a PDF version on my laptop, my tablet, and my phone; and an eBook version if I need it. In addition to their portability, these electronic versions have another advantage – the images of the fronts of individual stamps can be significantly enlarged should there be a desire to inspect them more closely.

I also have a PDF version on my laptop, my tablet, and my phone; and an eBook version if I need it. In addition to their portability, these electronic versions have another advantage – the images of the fronts of individual stamps can be significantly enlarged should there be a desire to inspect them more closely.

Oh, and, by the way, I did succeed in using Word’s BOOK FOLD function to print out two folios of catalogue pages which I stitched together and fixed into the back of the other countries album as shown below.

A summary idea

In dealing with some of last year’s Xmas cards, one from an old friend made me think again how powerful summaries are. The card has a tree on the front with names of sons, daughters and grandchildren round the edges. On the back is a photo of the grandchildren; and a link to an ‘Xmas newsletter’ is on a sticker inside. It has all the hallmarks of a good summary: easy and quick to access, informative but not providing too much potentially unwanted info, and providing clear directions on how to get to more detail. I tried this out on a report back in 1985 and think it worked reasonably well – but haven’t done it since and haven’t seen anything else like it; but my friend’s Xmas card has all the hallmarks. In these days of information proliferation such approaches ought to be researched, taught and practised widely. Some people may think that AI will be able to do this for us; but, be clear, we’re not talking about a simple ChatGPT textual summary – this involves graphics as well as careful selection of content. The question is not whether AI will be able to do this; its whether the result will be any good or not. For the immediate future we would be better advised to focus on educating people in the art of summarisation.

Springing into action

Yesterday Peter Tolmie and I reached a significant milestone in our work on a book about collecting in the IT era: we signed a contract with the publisher Springer. It commits us to deliver the completed text to their editors by the end of June 2024. We would expect to have a firm publication date by the end of that year. So now, it’s a matter of feeding in some additional material, refining our arguments, and modifying the layout and text to match the Springer Style Guide.

Choosing Rationales

Having explored the conversion of physical DVDs, engineered the delivery of the resulting files to the lounge TV, and experienced a few of the titles on its delicious 65-inch OLED screen, I set about deciding which DVDs I was going to hang onto. I ended up choosing to keep 20 of the 58 titles with the files totalling around 40 Gigabytes. One of my concerns when I started this journey was that the files produced would be too big to handle and, overall, would take up too much space. However, after adding this extra 40 Gb I still have 135 Gb of free space on my laptop which I consider to be sufficient for at least a few more years. The files themselves range in size from 670 Mb to 3.3 Gb – which is certainly very big; but at least there are only a few of them. In any case (I say to reassure myself) size is a short-term problem, as storage capacities continue to increase.

My rationale for keeping particular titles seem to fall into one or more of the following 5 categories:

- Watchability – productions that I can enjoy watching over and over again.

- Sentiment – productions that remind me of good times in the past or that I have a personal connection with.

- Spectacle – productions that are just awesome to watch with their extraordinary images and ambitious content.

- Instructive – productions that provide interesting and intriguing information.

- Music – productions that contain memorable songs or other excellent music.

This collection of files on my laptop would now appear to be a collection of my most favoured moving image productions; but, of course, it is not. They just happen to be the productions I particularly like in a set of DVDs that we just happen to have. A true collection of my favourite titles would entail trying to remember which items I have seen over the last seventy years that I liked best – an extremely challenging exercise. Finding and acquiring those items would probably be equally as challenging; nevertheless, it would probably be an enjoyable and rewarding hobby. However, I’ve never heard of anyone doing it in such a thorough way; only people who have collections of videotapes of a favourite TV series; or of DVDs. The reason is that moving image titles are dependent on modern technology – technology that is either transient like TV, or changing like cine/videotape/DVD. Books don’t have that problem: when people get a physical book, they can just keep it if they like it and they build up their collection of favourite titles over the years. Interestingly, the same has been true for physical DVDs. However, now that moving image has become a standardised software object, it’s possible that more people will gradually build up their collections of digital video files over the years. However, a physical book/DVD has a tangible presence in the world, whereas a software file is just about invisible. Furthermore, we now consume far more moving image material on a daily basis than we do physical books. These two distinctions means that our collecting habits associated with physical and digital media will never be the same.

Following this line of reasoning, I think it unlikely that I will start to add extra items in the future to my new collection of moving image productions. I might include the odd item in the Videos folder if it comes along in the right format and I particularly like it; but I won’t be making special efforts to capture material I enjoy on a regular basis. The collection will stay pretty static over the coming years, and may or may not get dipped into occasionally. As for the physical DVDs from which I have created the software files, I will keep those packaged away in a box in the loft. Not because I will ever play them again, but because I want to have some proof that I did actually purchase the DVDs which I ripped to produce the files: it is certainly illegal to make a copy of a DVD you don’t own.

What makes a DVD worth keeping?

I started assessing each of my DVDs several weeks ago and found myself splitting them into three groups: definitely keep, definitely dispose, and need to watch to decide. I’ll provide a summary of my conclusions and associated rationales, in a later post. First, however, I want to go into some detail about two DVDs in that final, ‘need to watch to decide’, category because I think they highlight many of the key points about keeping DVDS. They are the two sets of DVDS of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Olympic games set consists of 5 DVDs (approx. 15 hours running time) produced by the BBC; and the Paralympic set has three DVDs (approx. 7 hours) produced by Channel Four. I had Blu-Ray versions of both which my DVD player will not play. So, I bought ordinary DVD sets in eBay. This is a salient point about DVDS: they were very cheap – just £3.18 and £1.99 respectively inclusive of postage.

To provide the context for my subsequent remarks, you should be aware I’ve been a big athletics fan all my life. I did athletics at school, culminating in doing a decathlon at university. I also used to live next to Stoke Mandeville Hospital where the paralympics movement was born, and I took my young children out onto its track quite regularly. So, having the Olympics come to the UK in 2012, was a dream come true. I attended the Torch procession as it made its way through Aylesbury; and I got tickets to the Rowing, Boxing, Table Tennis, and the evening in the Athletics stadium when Rudisha broke the world 800m record and Bolt won the 200m. For the rest of the time, I watched the television coverage. It was all high octave and memorable. I specifically asked for the DVDs as birthday or Christmas presents because I knew I’d want to watch it all again. But I never did. They just sat on the shelf and my memories remained fond but grew dimmer. Until, that is, It came to this point at which I have to decide if it’s going to be worth keeping at least 8 very large files.

The first thing to say is that the Handbrake conversion was trouble free and produced results which had nothing to indicate they weren’t being played directly from the original DVDs. Secondly, streaming it over the home WiFi into the TV in the lounge from my laptop upstairs in my study also worked without a hitch: I just had to make sure that the power saving settings on my laptop were switched off to prevent the machine closing down during the running of the DVD. Thirdly – and this is a significant point – I found that being able to watch a spectacle like the Olympics on our large 65-inch LG OLED screen is an order of magnitude better than watching on a smaller screen. The screen size and clarity doesn’t just enhance the experience; it turns it into something much closer to a lived experience.

Now, let’s talk about the contents: the sport, of course, is the focal point of the Olympics and Paralympics, and it is undoubtedly very good to watch again – especially as only the highlights of the many days of competition are included. However, the sport is sandwiched between Opening and Closing ceremonies for both Olympics and Paralympics, and these were extraordinarily good. I had forgotten just how good. The themes, the costumes, the lighting shows across the seating areas, the ability to bring on innumerable well-known musicians and other celebrated people (including Stephen Hawking and Tim Berners-Lee), the innovative and daring expositions of our culture – well, it was all breathtaking. The Olympics Opening ceremony actually had a cricket match being played adjacent to a field with sheep in, and another field with wheat in which was being hand-cut – really; and shortly afterwards all that had been replaced with large factory chimneys. And so it went on, the standard being maintained across all four openings/closings. The scale of the productions and the coordination required across hundreds of performers and many different elements (including lighting, performers on wire suspensions, sound, and stage prop movement) was hugely demanding and yet seemed to be carried out flawlessly (though there must, surely, have been some hiccups?). The amount of design work that had been undertaken to underpin the final results was illustrated in one short extra file explaining the thinking behind the ‘House’ scene in the Olympics Opening ceremony in which the last 50 years culture of a typical family is represented over 10 minutes with laser projections onto the house.

With the big screen exploding with activity and colour and the sound turned up to reproduce the roars of the crowd, I became immersed in these 22 hours of extraordinary entertainment. I had forgotten most of the detail of the opening and closing ceremonies so I was reliving and enjoying the experiences again as though they were new. Having watched the Paralympics Closing Ceremony yesterday afternoon, I feel as though I’ve just attended the whole 2012 Olympics/Paralympics again; and what a time it was. It demonstrated the huge depths of creative talent the UK has across many different disciplines; it recounted our history and our culture – an open, caring, supportive, and inclusive culture; and the thousands of volunteer helpers did a magnificent job looking after the visitors to the games. It was a massive, triumphant, success; a platform for the nation to move forwards still further in creating a happy and prosperous society. Such a shame that it was all thrown away in the ensuing ten years. However, that’s by-the-by. The point is that I feel I’ve relived the whole extraordinary experience; and perhaps that’s what we want out of a DVD that we might want to watch again. We want to take what we considered to have been an extraordinary experience, and to be able to relive it and to recapture those feelings again.

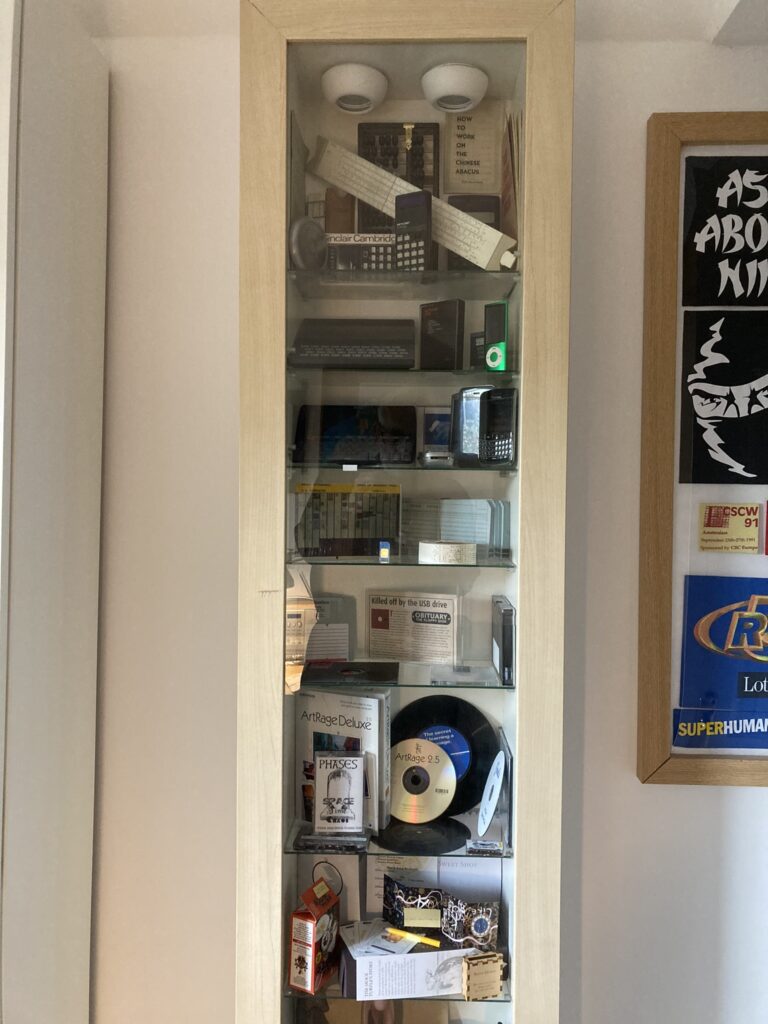

The Physical Display Case

Over the last 24 hours I’ve been curating an exhibition of vintage computer artefacts. Well, not really. In fact, I’ve just been repopulating the display case that I emptied when I moved it. But I have tried to apply a bit of rationale to my selections to try and get a bit of an understanding of the issues that real curators face. As is evident from the images below, this has resulted in a significantly different display from that which was in place previously.

I deliberately chose to make the new display a lot less cluttered to enable viewers to settle their eyes on just a few specific items. However, this inevitably led to what is, I guess, one of the main challenges that curators have – having to make difficult choices not just about what to include but also about what to leave out. Following on from the selection activity, I encountered a variety of other curation issues including:

- Having to go to and from the storage area (in my case, the loft) to collect different items is a time-consuming and irritating process (my selection decisions were taken on a shelf by shelf basis).

- Having limited shelf space means that some topics, or groups of artefacts, that would be desirable to include, simply can’t be accommodated.

- Sometimes a choice has to be made to either put like objects together regardless of the date they were made; or to keep items from the same rough date of manufacture, together.

- Stands or other mechanisms are required to enable objects to be displayed upright instead of lying flat on a shelf.

- Items at the front of shelves can obscure items at the back of shelves.

- Shelves closer to the floor are more difficult for the viewer to see to the back of, or to inspect closely.

As for providing descriptions – well that’s another level of complication I haven’t ventured into. I imagine it would significantly reduce the space available for artefacts; and decisions would have to be made about how much information to provide. My let-out for not providing descriptions is that some further information and extra images are available in the digital display on the iPad.

The job of a curator clearly requires a wealth of knowledge, skill, and experience. Right now, I’m on the very lowest rungs of that ladder.