A couple of weeks ago I joined UCL’s free – and excellent – 8 week online Digital Curation course. It has several hundred participants from all over the world – many of them professionals and students in the Archiving and Curation field. The course covers what digital curation is, how it is performed, and its major activities and communities worldwide, as well as leading participants through some practical digital curation work on their own files. This latter activity is a perfect fit with the trial I am currently performing of an approach to creating and planning a Preservation Plan. The course also encourages participants to discuss what is being taught and, although I’m actually doing digital curation work, I’m an amateur with no training, so I’m finding it very valuable to listen to the perspectives of specialists in the area.

Last week in the course we were asked to write about our digital mindset – our early experiences with computers and any turning points where we suddenly became more aware of the digital world we are now in. This was my (slightly augmented) contribution:

I first came across computers at university where we handed our punched card programs into the Computer Dept and collected the results a day or two later. In my first job in Kodak I experienced computerised stock control, sales estimating and factory production planning, and was fascinated. I became a Needs Analyst. However, it wasn’t till I joined the National Computing Centre’s newly formed Office Systems division in 1980 that the digital penny really dropped. The job was to seek out best practice and spread it to UK organisations. It was a time when Word Processing was gaining ground, personal computers were being introduced and electronic mail was just emerging. Within a year I knew that the future for the individual, both in the office and at home, was digital. I plunged in enthusiastically. I started filing all my documents using an index knowing that eventually the index would be computerised and that the documents themselves would be digitised; I replaced my pocket and desk diaries with a constantly updated folded A4 page that I kept in my wallet; and I rushed to work early in the morning to furiously communicate with distant colleagues in the British Library electronic journal project BLEND. By the time I took my next job in 1984 my path was set and the remaining 26 years of my career were spent harnessing the increasing power and lowering costs of computers to augment my digital visions. At home, we started budgeting on the EazyCalc spreadsheet, our addresses were held in a database, and I started indexing and scanning every family photo. At work, my wallet diary was eventually replaced by an Organiser and then mobile phone (though my wallet diary sheets are the best diary records I have); and I immersed myself in email, Computer Conferencing services, and research in configurable message systems. My file index was computerised on a Mac and eventually I started scanning my documents into a document management system. Shortly afterwards I started to experience preservation anxiety when I realised that this ever expanding, increasingly precious collection of all my work knowledge was utterly dependent on the next 30 years of effective back-up procedures and flawless migrations through many upgrades of three software products, the operating system, and my laptop.

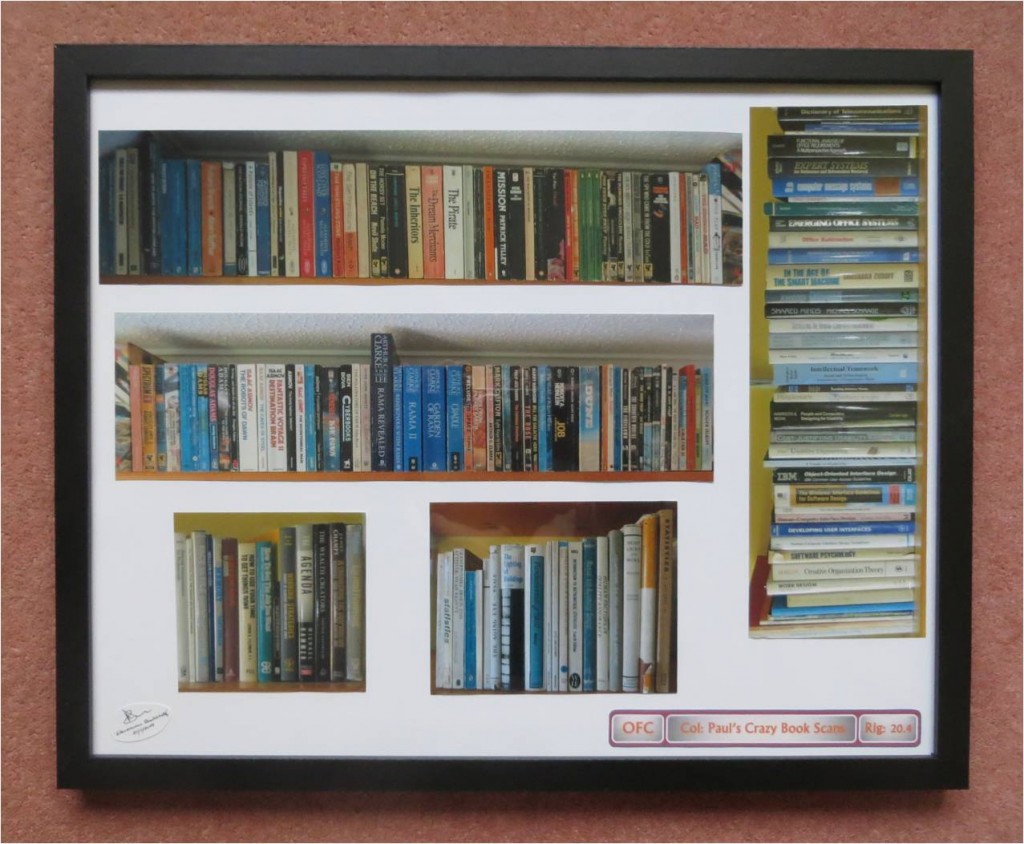

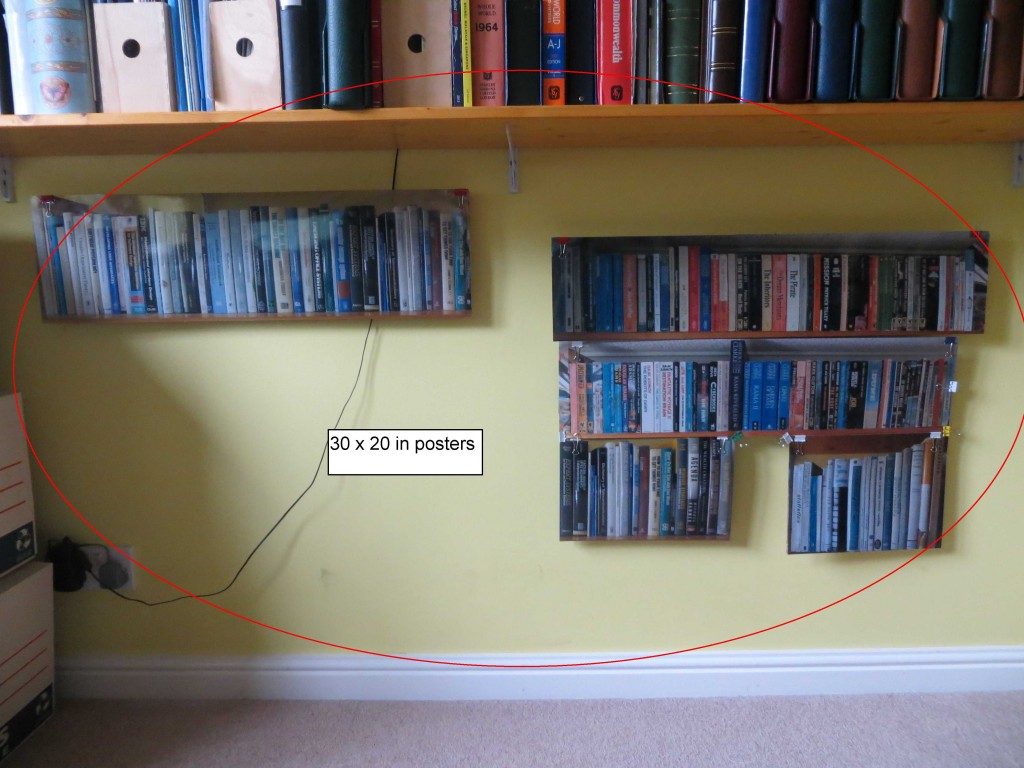

When I retired in 2012 and was released from the overload hell that email had become, I had time to digitise the boxes of mementos accumulated since 1958. So, now I have a 33Gb digital collection of all my work documents (approx 180,000 scanned pages) which is in serious need of a preservation plan and a final destination. I also have a 44Gb collection of 17,000 family photos, and a 7Gb collection of 1600 digitised family mementos – both of which have a destination (my offspring) but which also require a preservation plan and a mechanism for informing, and handing them over to, the unsuspecting recipients. My digital vision for the workplace has long since been achieved; but there is much left to explore in the home – how to show, share and bring to life our physical and digital objects, and how to ensure they are reliably passed through the generations; and of course, ways to allay the ever-present preservation anxiety associated with such precious collections.