In my last entry on this topic I mused if I would get a response from the developers to some suggestions I had sent them; and I was awaiting a new version of the mobile app which apparently was going to resolve some of the issues I had. After 5 months, sadly the answer to both points is NO! I’ve had no communication from the developers whatsoever – they seem to have missed the growing trend to interact with customers. And the new mobile app doesn’t seem to enable users to limit the number of different versions of an article that a user is informed about; nor does it make it any easier to find a particular journal amidst the many hundreds published by Taylor & Francis.

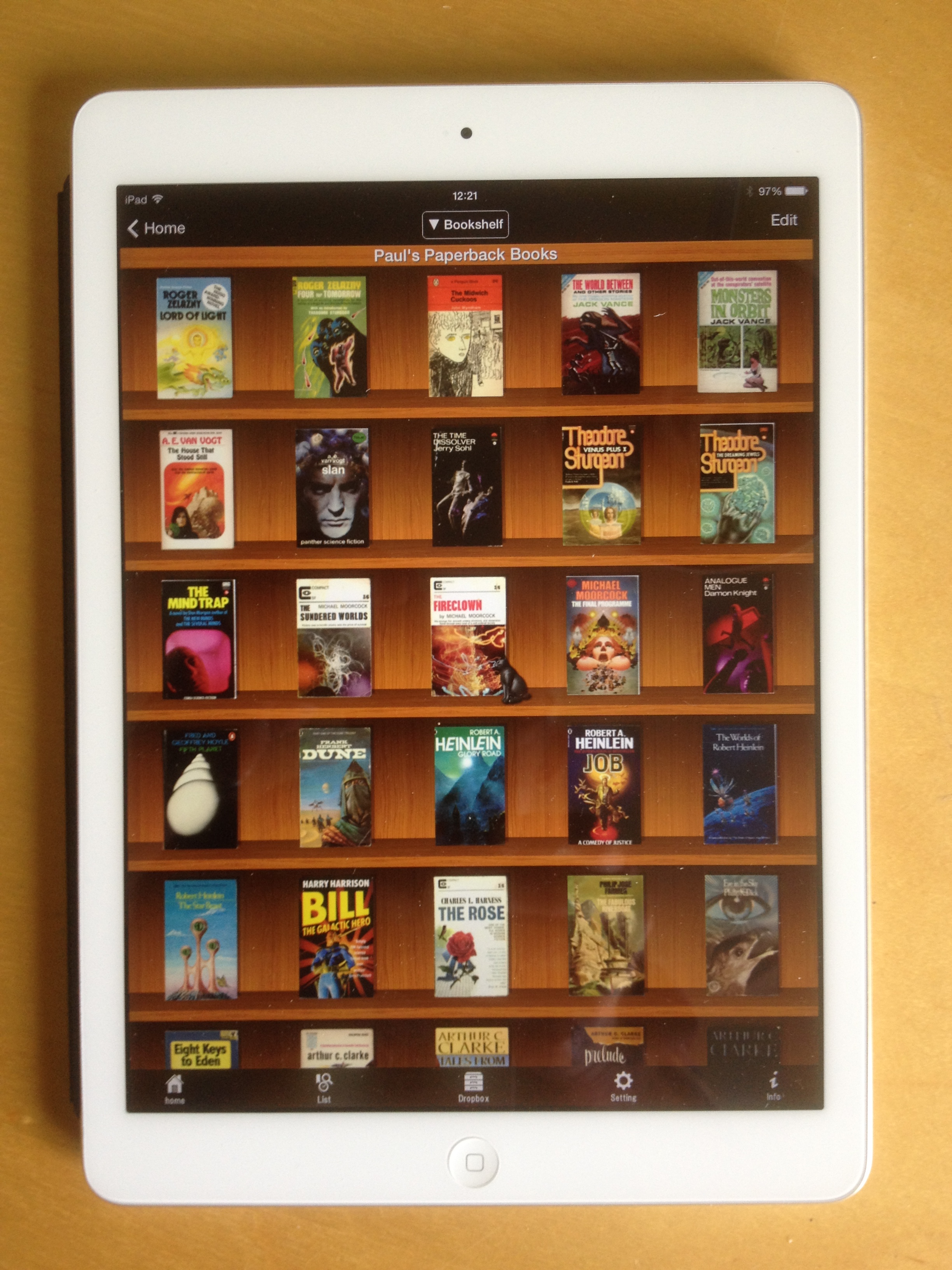

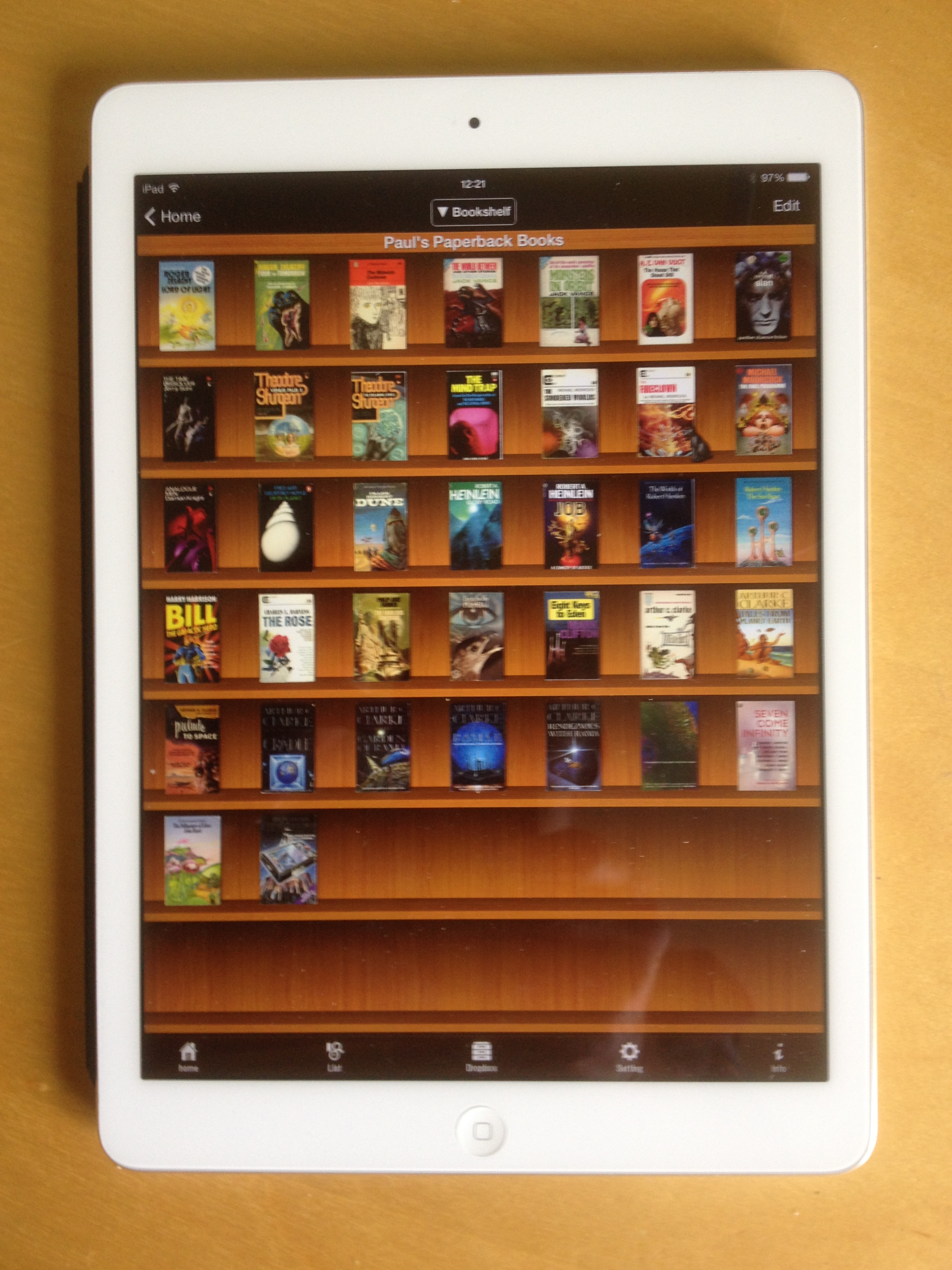

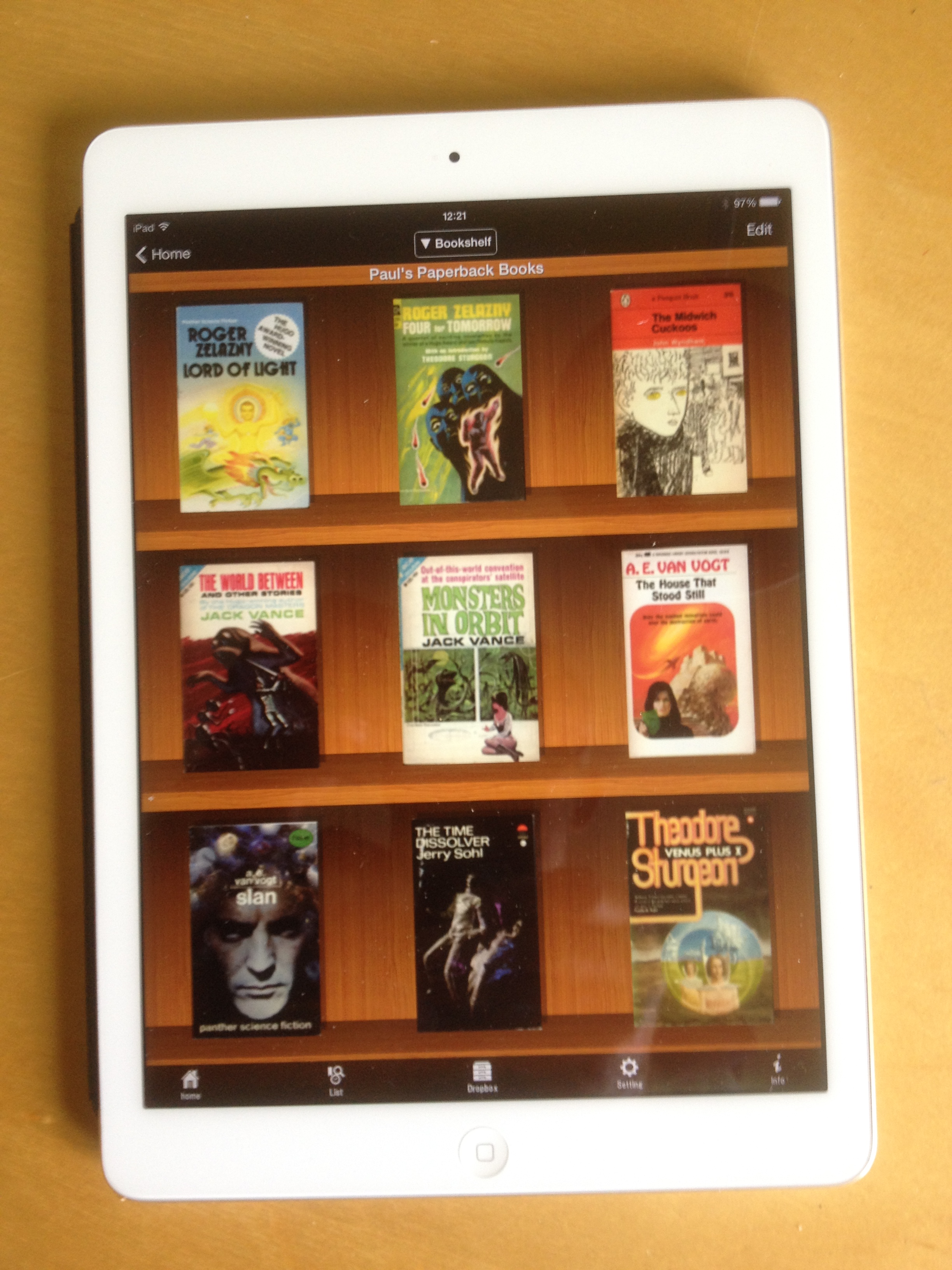

However, I think I’ve had enough with messing about with this. I’ve simply stopped taking too much notice of the alerts as they come through in the email. If an article was really of huge interest I might open it up, but otherwise I just wait till I get the email of a full issue when it’s published and at that point take a look at particular papers and if one is particularly interesting I’ll download it to my document management system and make an entry in my index. Of course this is exactly how I used to do it when I got the hardcopy version of the journal, so I guess, in my case anyway, the promise of a more immediate journal experience has not been realised, except for those rare papers which have titles which inspire a specific and special interest. The price of being able to spot those special few is having a significant number of alert emails added to the mail queue. Is it worth it? Well, I’m not so sure, but at least that’s one thing that is somewhat user configurable – you can elect to have the alerts Daily, Weekly, Monthly or Never. Unfortunately the functionality to just be alerted when a new issue is finally published seems to be missing despite the text in the settings seeming to indicate that such a choice is available. I’m afraid that’s the final straw – this organisation isn’t really bothered about the individual end user, and I have other things to do with my time. I’ve found that taking a journal electronically does work for me – especially when reading it on an iPad – but I suspect there may be better overall user experiences to be had. It’s time to get of this bus.