In December 2024, I was given a rather unusual birthday present by my daughter and her husband. It was a subscription to an internet service called My Life in a Book. The service sends you a different question to “help you reflect on key moments in your life” every Monday for a year; and provides a web site in which you can write your answers (which can include images as well). After 52 weeks you tidy up your manuscript, select and edit a cover design, and then press ‘Print’ to have your stories “beautifully bound into a cherished keepsake book”. The gift included 1 physical copy of the book.

After receiving an introductory email advising me of the gift, I duly received my first question the following Monday. It read “ Hi Paul. Your question of the week is ready” and provided a button to take me to the writing web site and the question “What are your favourite childhood memories?”. This was the pattern for the following 12 months (I believe that the person who buys the subscription selects the questions from a pick-list). Sometimes I was too busy to answer straight away, or simply wanted some time to think about my answer, and in these cases I either did not respond to the email until I was ready; or else I accessed the question, inserted some placeholder text, and labelled it as ‘draft’. I found some of the questions really quite hard to answer; for example, “What were your greatest fears about becoming a parent?” or “How do you navigate decision-making when confronted with uncertainty or fear?”. Initially, I dealt with these by selecting the option to skip a question but, as the year wore on, I thought better of it on the assumption that any honest answer – even along the lines of ‘I don’t know’ – would be worthwhile. However, if I had skipped a question I could have simply replaced it using the facility to create your own questions at will (the answers are essentially text blocks which don’t have to relate to a question – they can be sections of any kind – Forward, Contents, Introduction, Index etc.).

The editing facilities in the writing platform have clearly been designed to help people unfamiliar with word processing systems, to produce their answers: the margins, font, and font size are all predefined with no choice. However, bold, and italics can be specified for selected text. The facilities to edit imported images are also limited: there are three size options – small, medium and large – and the ability to crop. This overall limitation of choice is quite refreshing, relieving the writer of having to take a variety of actions.

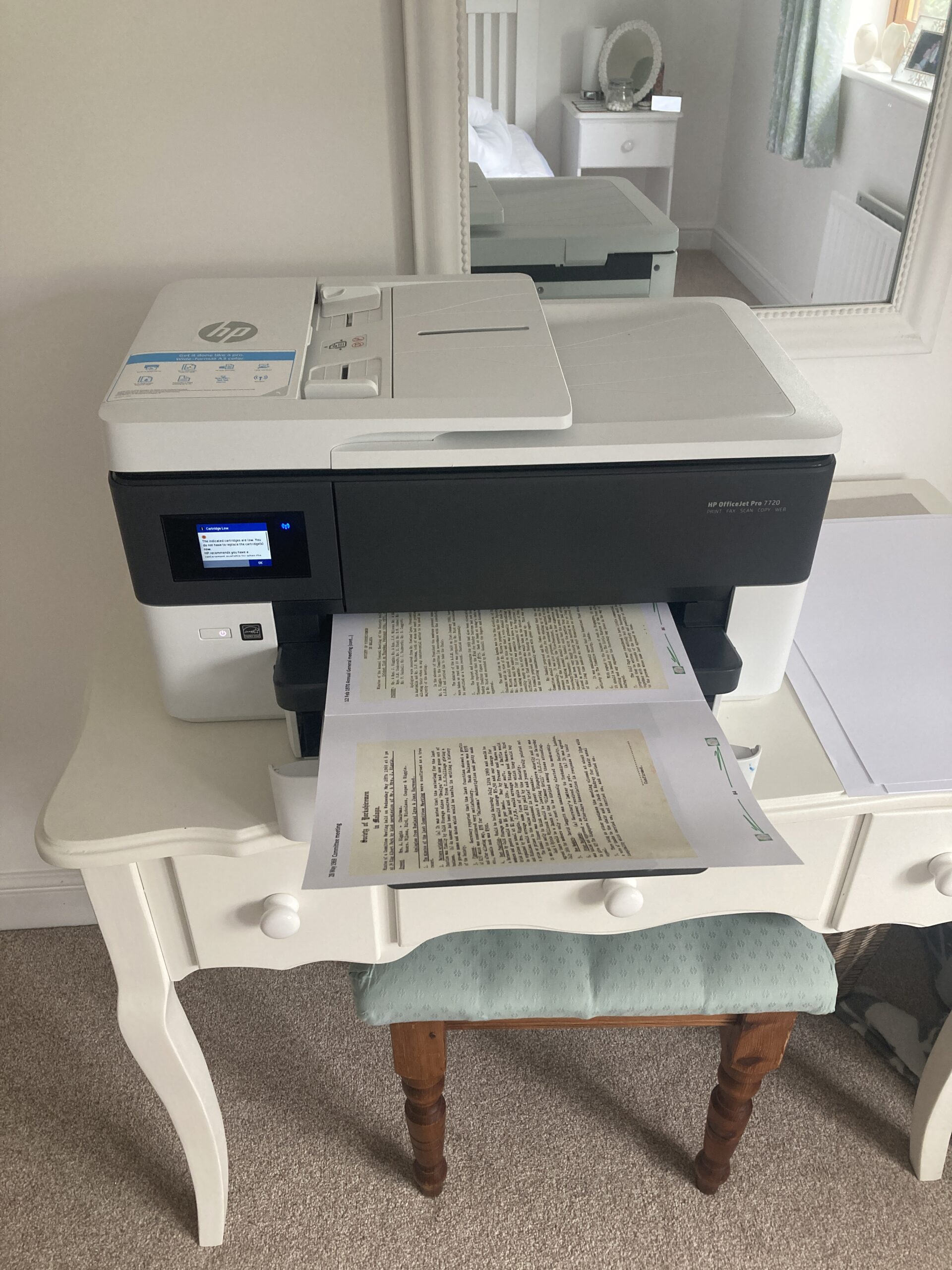

The final version of the book is produced as a PDF file with page numbers, which can be reviewed at will. Unfortunately, this disconnect between the editing facility and the PDF version does mean that, while you are writing, you can’t be certain whether imported images will fit onto the bottom of a page or will get moved to the following page leaving a large gap. To check, the PDF has to be generated which, in December 2025, for my book of around 230 pages, was taking at least 40 seconds and sometimes a lot more (I’m guessing that response time is dependent on system load and that a lot of subscriptions were coming due around Christmas). A further annoyance was that, for a reason I don’t understand, the changes I made to image size didn’t seem to appear until I had generated the PDF version for a second time. Hence to ascertain whether an adjusted image was going to fit onto the bottom of a page was taking me around a minute and a half or more – very frustrating, especially when finding that the adjustment you have made was insufficient and the image is still being pushed to the following page leaving a large gap. A fourth option – “Fit at bottom of current page” – to go with the small, medium and large image sizes would really improve the system’s usability.

Other than the issue described above, I found the system generally easy to use and flexible enough to include whatever content you want. For example, although each answer comes with a suggested heading, the user can change the heading text at will. I used that ability to add numbers to each heading and then created a Contents page (which is not automatically generated). I also created a Preface section.

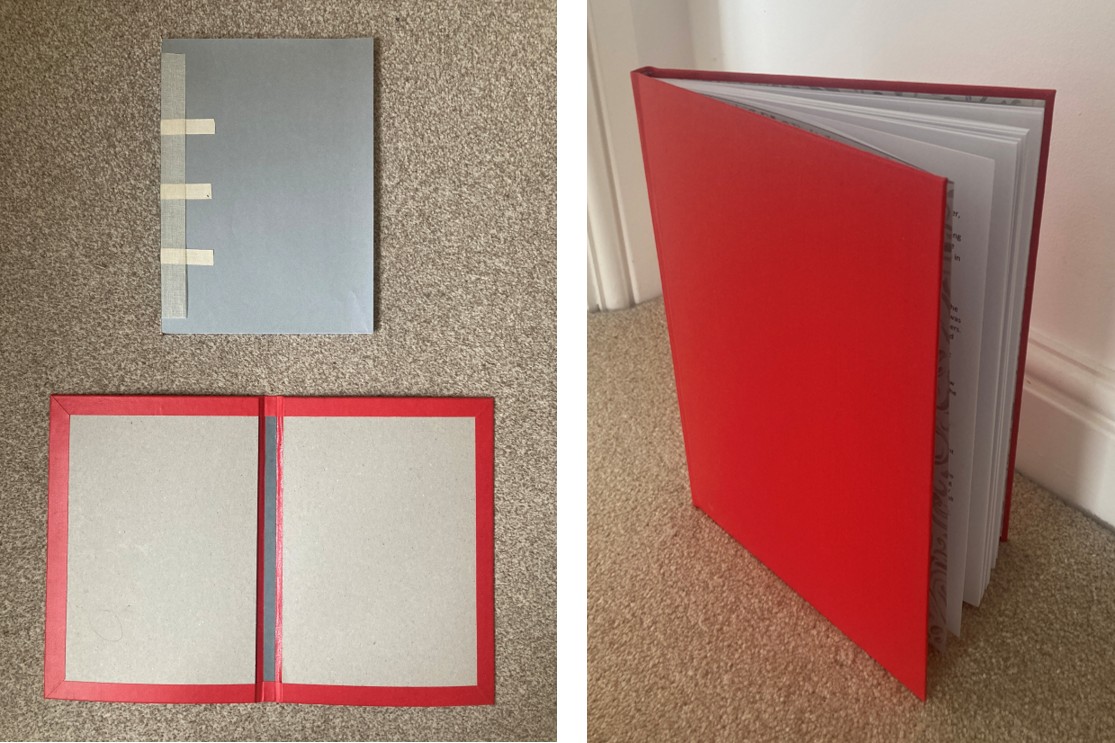

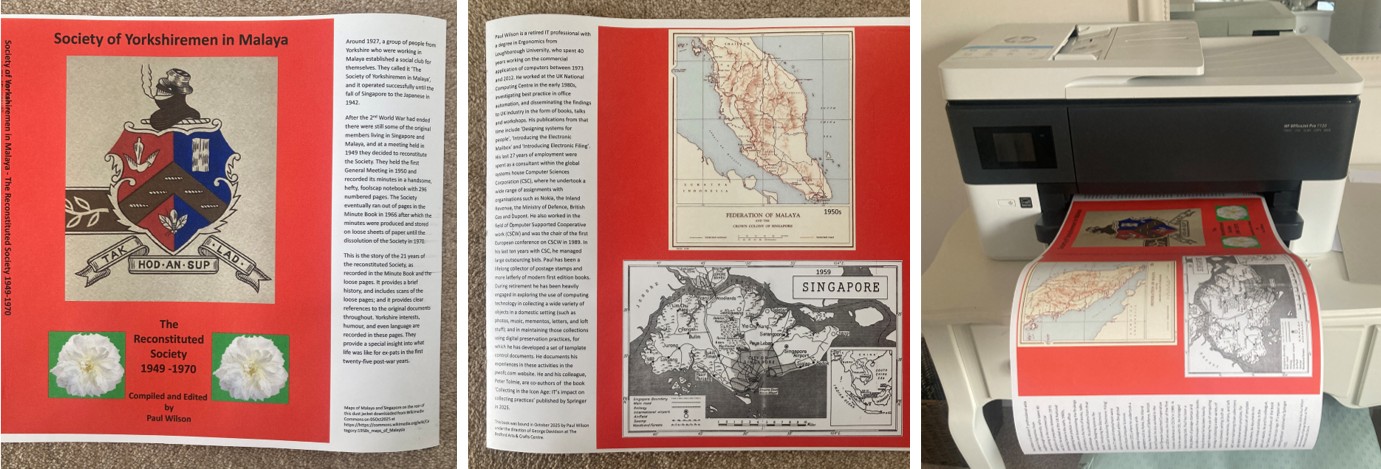

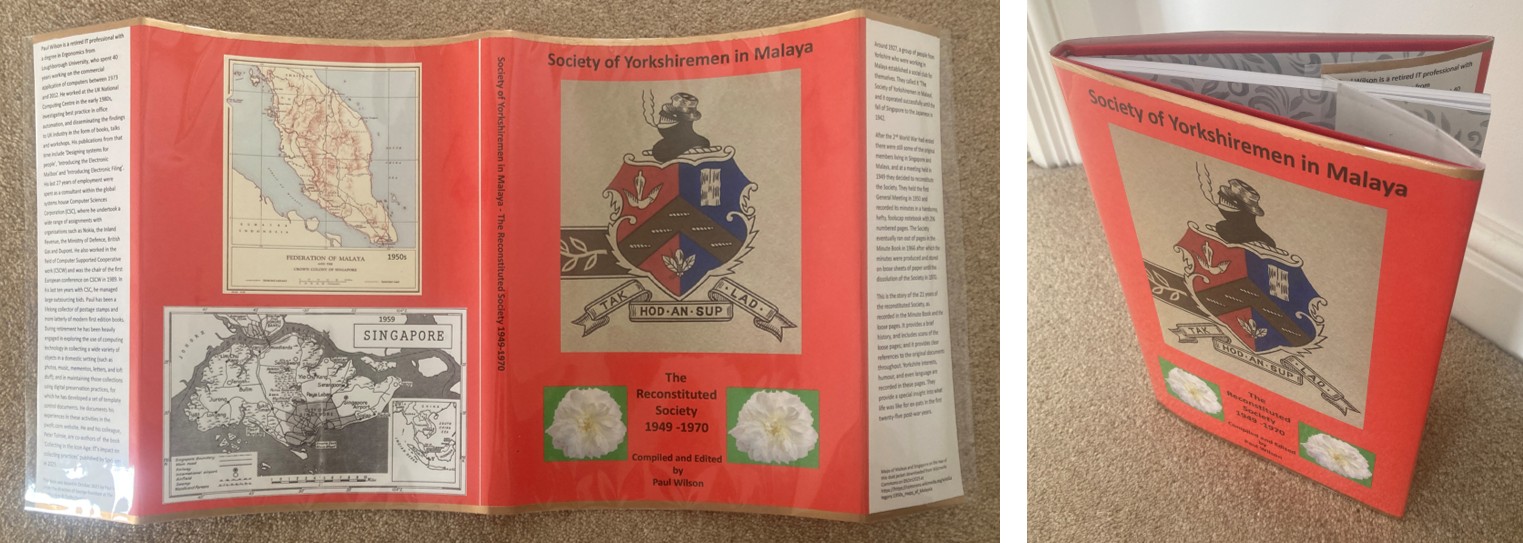

Having completed the content of the book, the web site guides you through a completion process which first advises detailed checking of the contents using the preview PDF (essential, as bitter experience has proved to me it is almost impossible to spot and remove all typos, grammatical errors and factual mistakes from the draft of a book). I was then asked to choose a template book cover from a choice of several dozen designs; and to supply a title, author and image, which were automatically included in the template. When I was satisfied with the book cover, I was taken into the ordering process where I specified where I wanted the book to be sent, and the number of copies I wanted (whoever bought you the gift will have paid for one or more printings, however additional copies can be purchased). That was the 10th of December; then it was time to sit back and wait for delivery. I received confirmation that the book had been printed and shipped just two days later; and it was delivered by Royal Mail 5 days after that on 17Dec – which I thought was an impressively fast turnaround.

The book itself is around A5 size and looks quite good. The text block appears to be secured to the case only by the end papers so I’m not so sure how long-lasting the joint will be – but the book does open satisfactorily. The text is clear and an easy-to-read 12pt in size; but the images, though perfectly adequate, are less than pin-sharp. However, there was one thing that was wrong: the printed Contents list had slipped over onto three pages whereas the PDF I had checked showed it on just two pages. Consequently, all the page numbers quoted in the Contents list were out by 1 page. I immediately used the web site chat facility to report the problem and was told that someone would get back to me.

The following morning, I was asked to provide photos of the problem and to specify the type of device and browser that I was using. I responded saying, “The device I’m using is a Windows 11 laptop with the Firefox browser (version 146.0 – 64-bit)”. I was then told that,

“It seems the issue may be related to the browser you used. Please know that while this is rare, we’re working to ensure all browsers display the correct format. That said, we will take full responsibility and send you your books again at no extra cost. To ensure everything appears perfectly this time and to prevent the same issue from happening again, I encourage you to log in to your account using Google Chrome and make any necessary adjustments. Once you’ve made the changes, please let us know, and we’ll provide a PDF copy for your final review. After you approve it, we will reprint your book and ensure it is sent to you as quickly as possible.”

A subsequent exchange confirmed that it would be worth trying with Microsoft Edge which I duly did; and after comparing with the PDF I was sent, all seemed to be well and the book was sent for reprinting on 21st December. The two replacement copies were delivered to me by Royal Mail on 27Dec – and they did have the correct pagination.

I felt so pleased with the support I had been given that I was prompted to send the following message to the support team: “I must say that the response of you and your colleagues in the Support team has been an outstanding example of prompt and excellent customer service.”. Having said that, though, the problem I encountered should not have happened, and my euphoric response probably also had something to do with the fact that my general experience with online support these days is poor. Furthermore, my subsequent dealings with the support team were less satisfactory and revealing – but more of that at the end of this post.

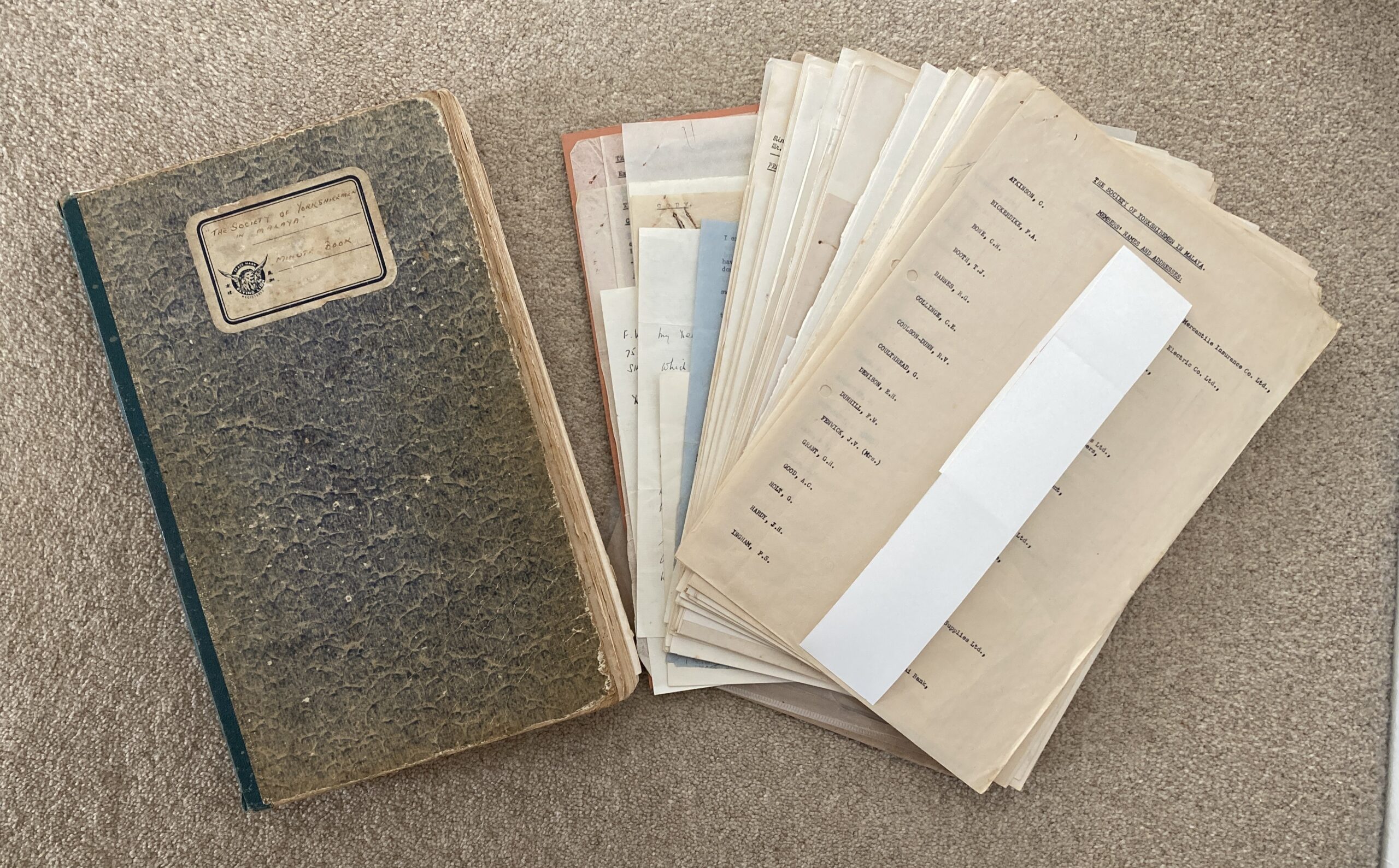

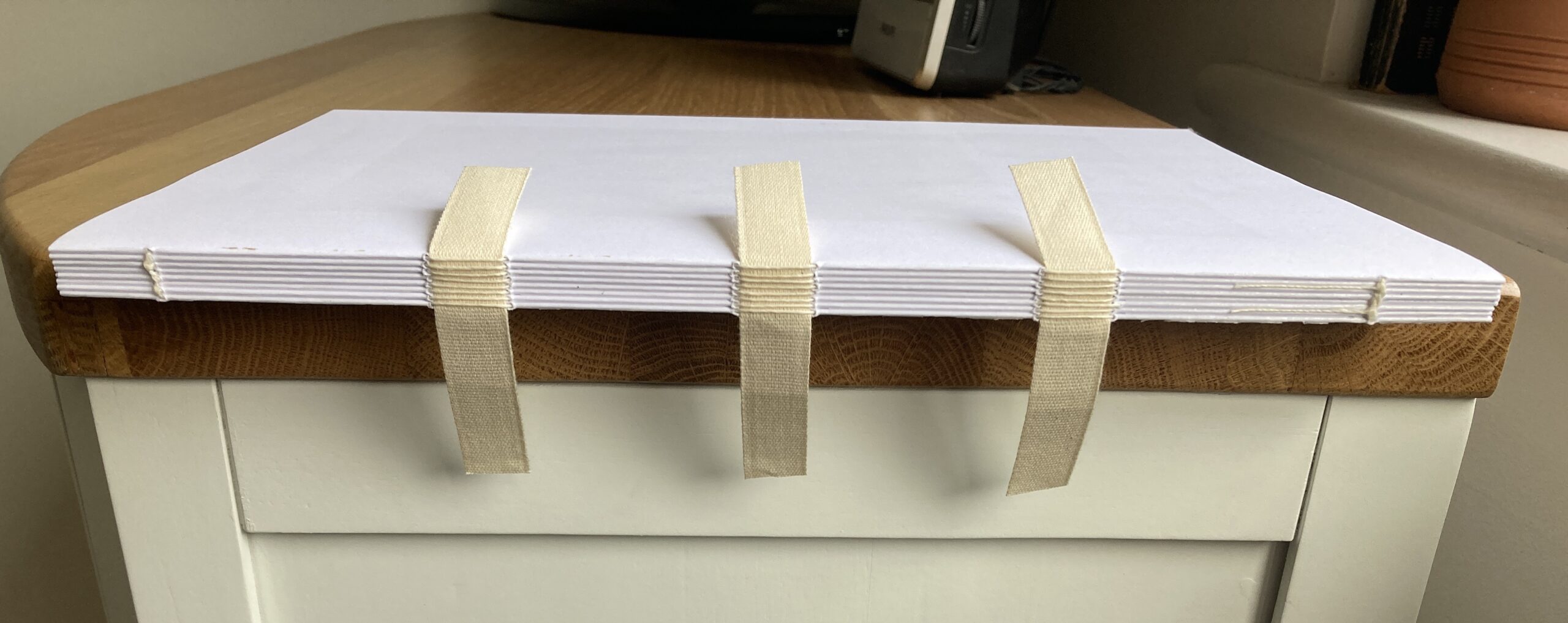

So, having completed the whole 12-month cycle of My Life in a Book (MLIAB), how do I feel about the experience? Well, it certainly prompted the exploration, re-use and perhaps rethinking of old memories and artefacts; and it’s satisfying to have the results all neatly packaged up and sitting on my bookshelf. The completed book is intended as much for the current family and future generations as it is for me (as is pointed out in much of the MLIAB promotional material), and, as yet, I have no idea what my daughter and her husband think of the artefact they commissioned; nor what my other offspring, who will be the lucky recipients of the copies with incorrect paging, will think. Perhaps they won’t even read it. However, as the author, I do know that I made some specific choices about the content. First, being conscious that the book might well be perused by all members of the family, I was careful to be inclusive and not to favour anyone in particular. Second, I naturally only included material I was happy with other people knowing about. Thirdly, some of the contents are things that the family almost certainly will not have been aware of; and fourthly, after I’d finished, I began to have doubts about some of the material I had included; and inevitably started to think of other things I could have included – but I certainly wasn’t going to take up the service’s offer to extend the process: one year was quite enough answering questions, researching, and editing. Overall, I think it’s a pretty effective way of exploiting one’s collections of mementos, photos, correspondence and other personal material – but it does require work and persistence.

I should mention a couple of other things at this point. One is that the marketing effort by MLIAB is one of the most intensive I have ever experienced: during December I received over 40 general marketing emails unrelated to my account or the book I was producing. The other is that there are several other similar services available on the net (for example, The Story Keepers, Storyworth, Remento, and No Story Lost), but I haven’t investigated any of them.

Now, to return to my further dealings with the Support team. Throughout my exchanges with them I’d been a little bemused by the gushy nature of the responses. It wasn’t normal and smacked of AI (see messages 1-6 in this linked file). This view was cemented in the next message (Message 7) that I received in answer to me asking if they had encountered the problem with the generation of the PDFs and if they knew what the cause was. The response was strangely imbalanced. It ignored the issues associated with PDF generation and instead it explicitly described how large images are placed onto the following page leaving gaps – a fact I was very familiar with – and was gushing about a potential solution I had offered. At that point I replied with the question, “Julia, are you and your colleagues Pauline and Sandra real? How much of your reply below was generated by an AI Large Language Model (LLM)?”. The reply insisted that they were real people aided by tools such as AI (see Message 8 in the linked file).

Now despite my satisfaction with the way my book had been reprinted, there are some hard facts about customer service to be taken away from these exchanges:

- The positive impact of warm, gushy, language just disappears after it becomes obvious it’s machine generated. At the point I confirmed what was happening, I ceased to feel I was dealing with people and became rather hard-nosed and cynical – as will become apparent from my comments below.

- The fact that my PDF question had been ignored was very frustrating; but I decided not to follow it up because, in my experience, bots are useless when they are dealing with unfamiliar issues, and the organisations that implement them always seem more intent on saving headcount than addressing customer problems. The issue with PDF generation is a genuine problem that the MLIAB organisation should know about and be able to advise customers about. It’s disappointing that it wasn’t addressed in the response.

- Despite Message 8 insisting that all named members of the support team that I had been dealing with were real people, I’m not sure whether to believe it or not. LLMs are notorious for getting things wrong and saying what suits their prediction algorithms; and I think that organisations are all too often happy to obscure the real capabilities of their customer support operations. I may be wrong about the MLIAB support operation, but I’m afraid this is the view I now have after my experiences with a variety of bots and support operations; and after reading quite a bit about contemporary AI systems.

- Even if the messages to me were being reviewed by real people, the fact that my question about PDF generation had been so studiously ignored, suggests that either the reviewing wasn’t very good (or there was insufficient bandwidth to undertake a proper scrutiny of my question); or that the AI/people combination had deliberately decided to ignore my question.

- My overall attitude towards the MLIAB support operation is now one of ambivalence – despite its excellent response to the incorrect pagination of my book. I really have no idea how many real people they have in their support team, what their real names are, or how they actually operate. Does the AI create all responses immediately messages are received with the replies being quickly reviewed by real people (or even just a single person?); or do the real people look at messages from clients and then enlist the AI to create a response? Knowing that this is the way the world is going, I’ll inevitably have to draw on this experience when I interact with other customer service operations in the future. This will be a self-perpetuating vicious circle until customer service is once again considered important enough to give a sufficient number of human representatives the time to be able to interact in detail with all customers wanting help, support and answers to questions.