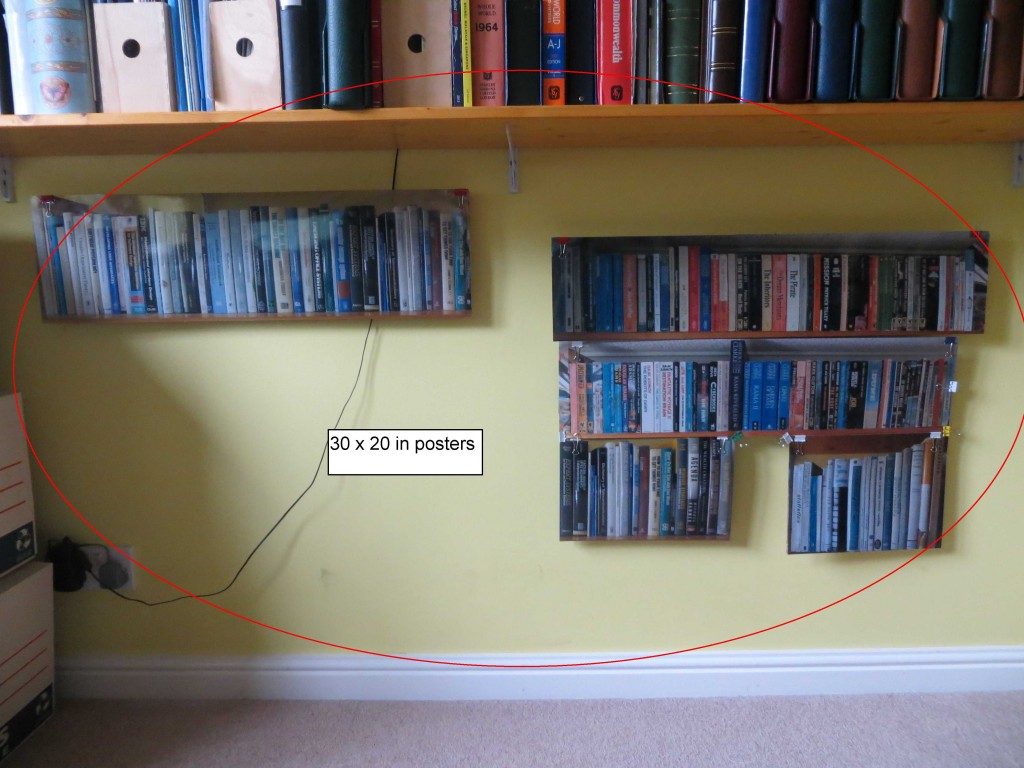

After spending 6 weeks with the four different sizes of bookshelf posters on my wall (40×30 in – full size, 30×20 , 18×12, 15×10), last week I came to these conclusions:

- While the full size version is easiest to see and read, the next size down – 30×20 in – is still perfectly usable;

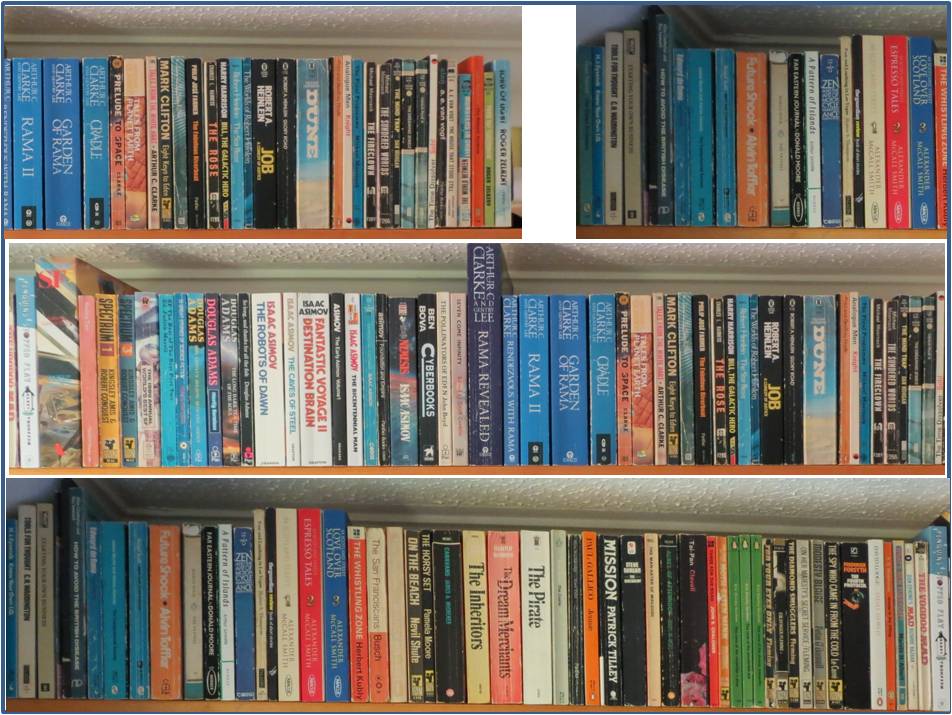

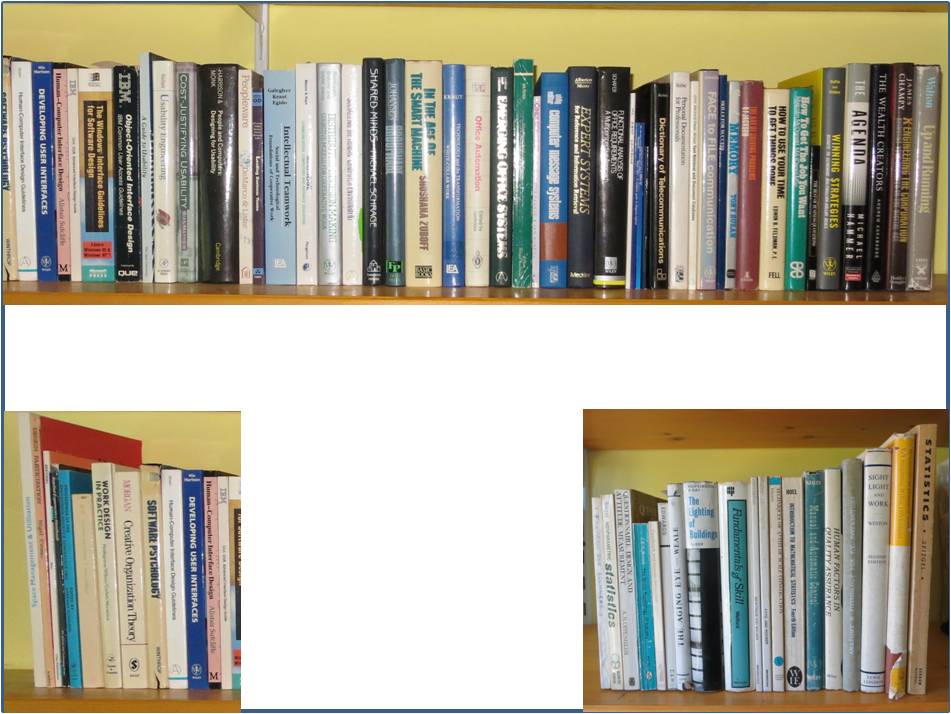

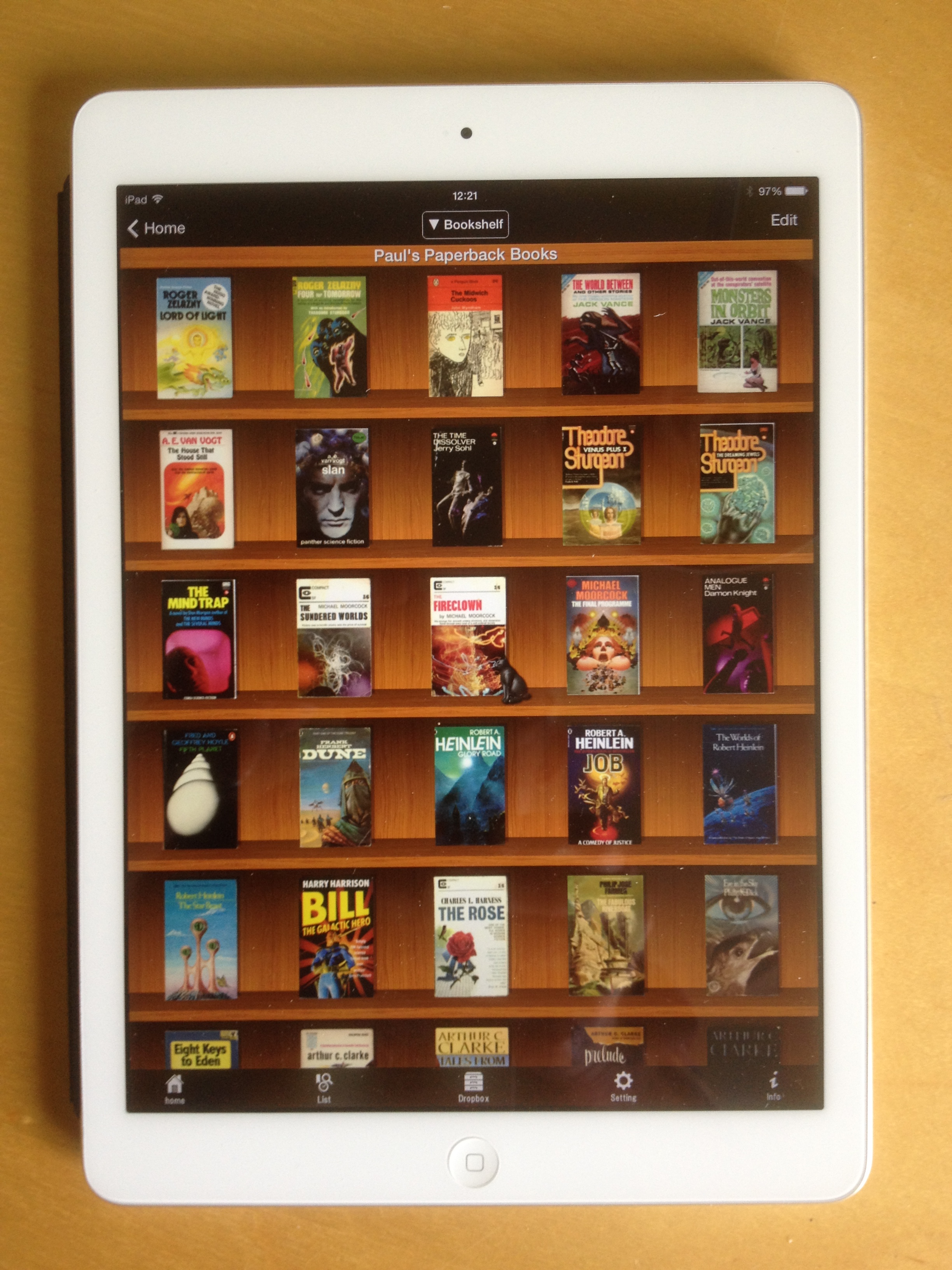

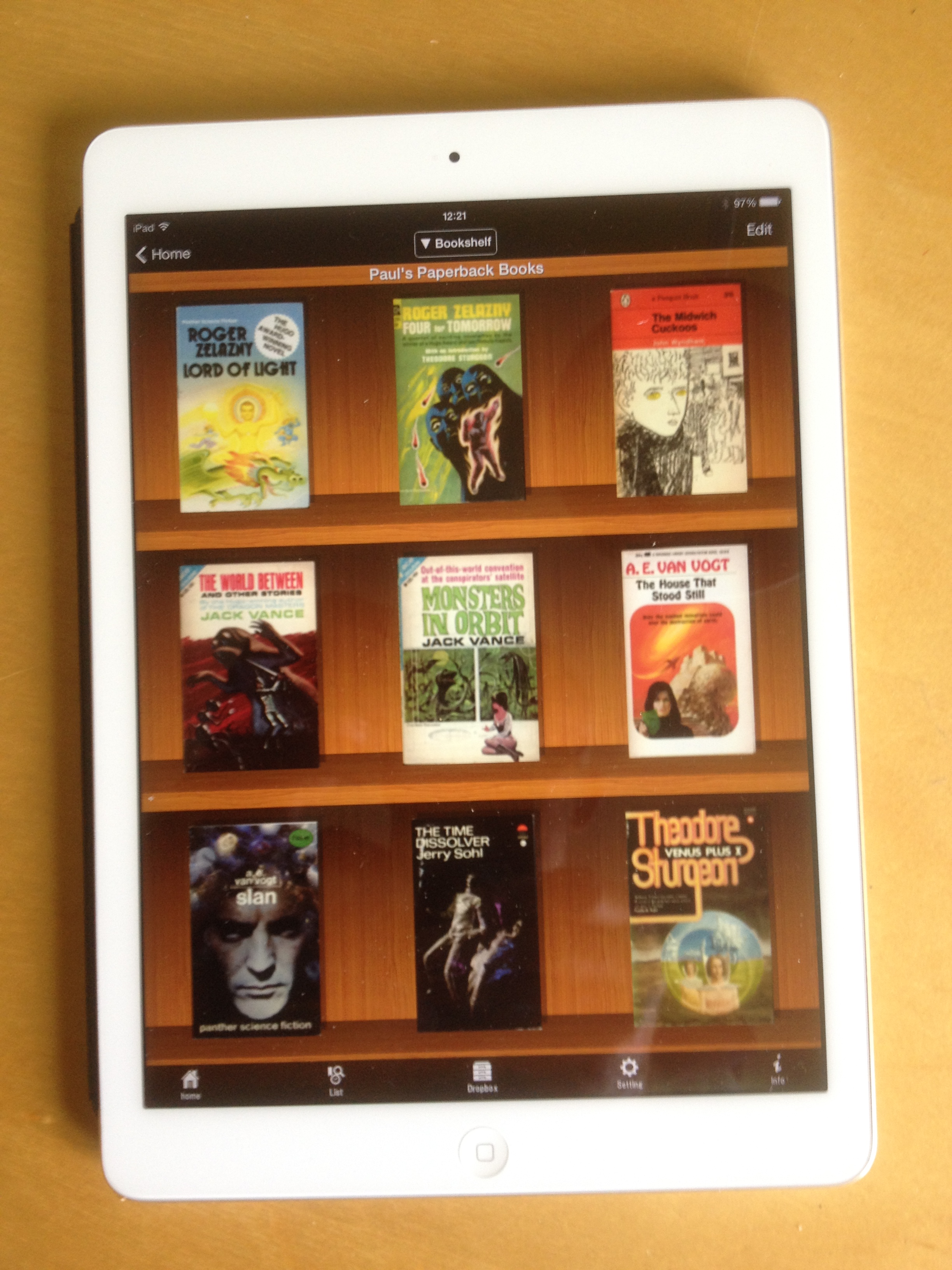

- Even the two smallest sizes provide sufficient detail to be able to distinguish between books and to find them in the iPad.

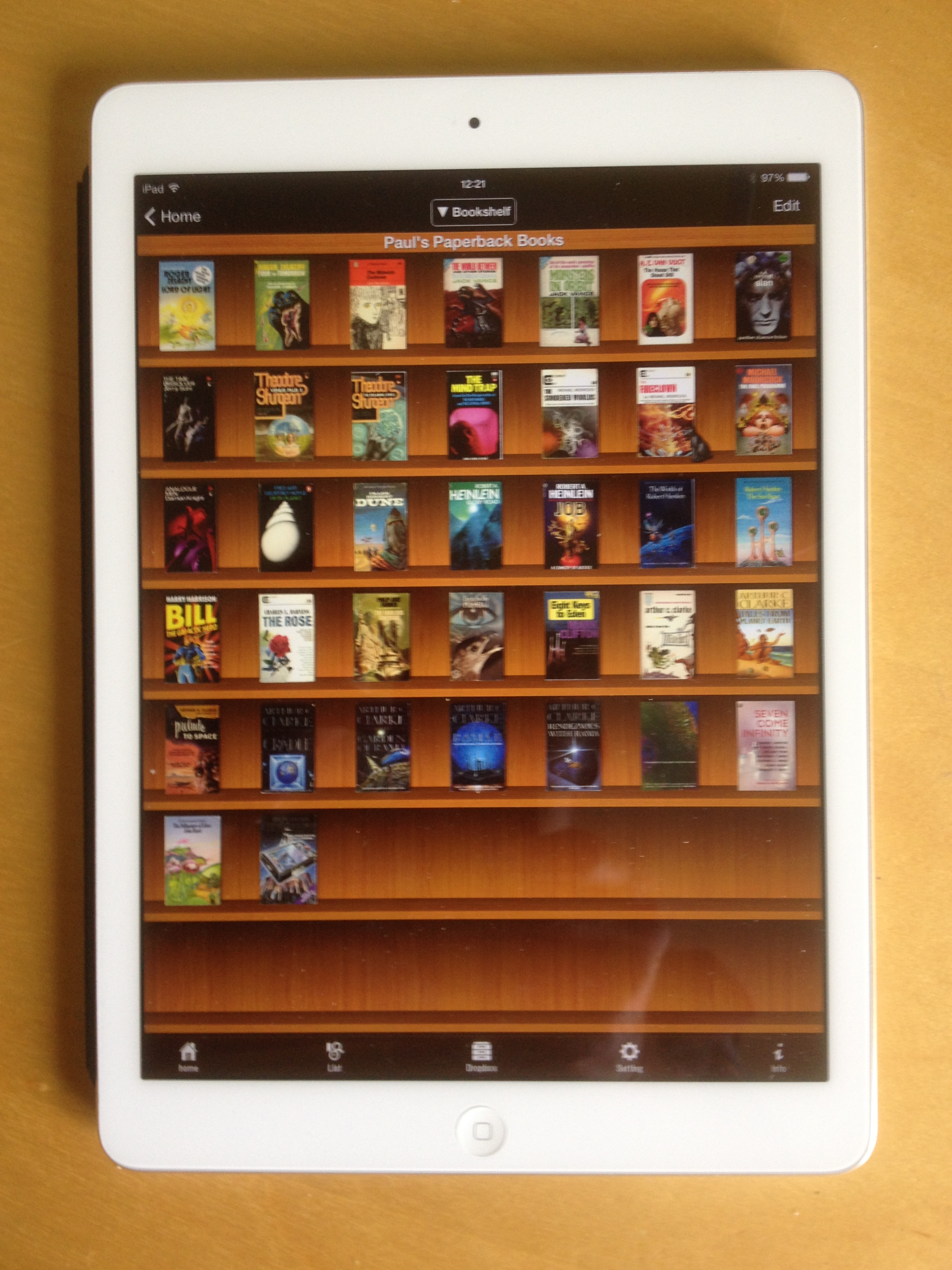

- Hanging the posters vertically so it appears as if the books are stacked one on top of the other doesn’t present a problem – in fact it makes it easier to read the book titles; however it might be better to remove the edge of the shelf running vertically down the poster and perhaps replacing it with a shelf at the bottom of the stack.

- As with ordinary books, its more convenient to view the bookshelf posters at head height; and it’s interesting to anticipate that a system displaying digital versions of the posters would enable shelves to be switched to the preferred height at will.

- The posters can be presented together in different combinations and arrangements, for example, the poster of a particular shelf can be horizontal or vertical and can be placed at the top or bottom of a group of posters. This would be easy to replicate in a system managing digital versions of the bookshelves

- Like the posters, digital versions of the bookshelves could be duplicated and displayed in other rooms or locations.

With these points in mind I decided to put the four different sets of posters to the following uses:

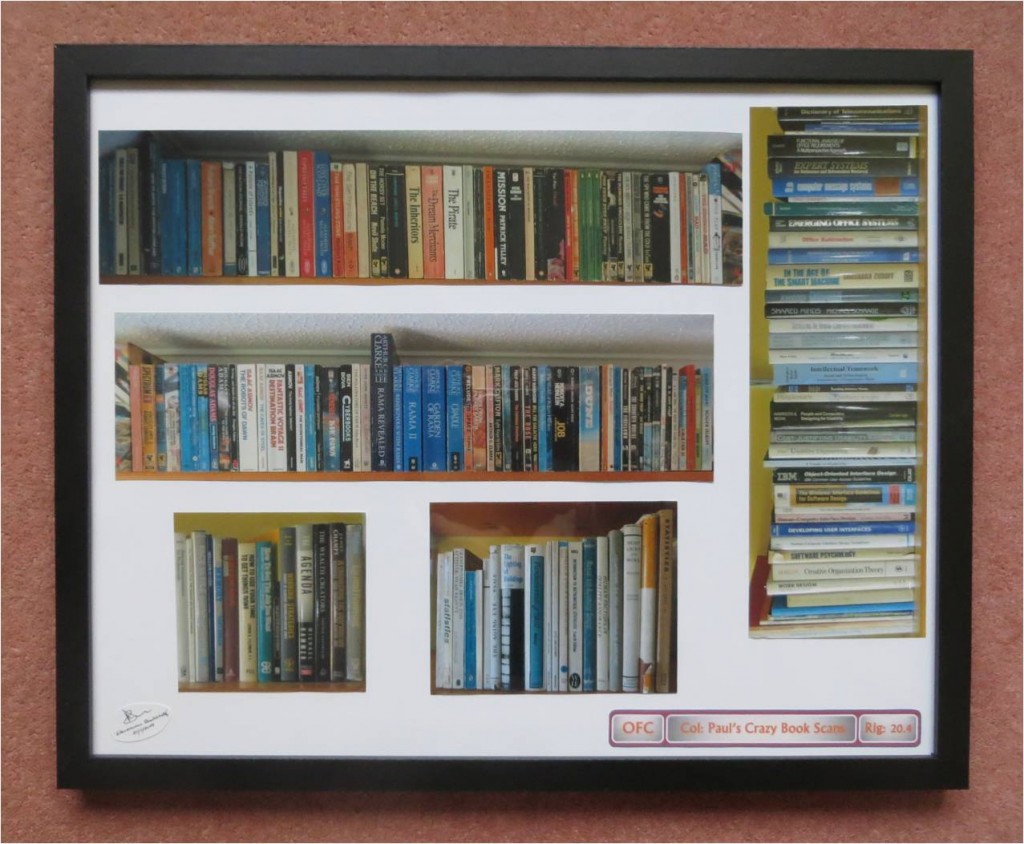

- The second biggest size posters have become my permanent visible images of the books I have scanned and which I no longer have physical copies of. They are arranged in a 40 x 30 in IKEA RIBBA frame which is on my study wall directly ahead of me as I sit at my desk. Being able to use the smaller-than-full-size posters has made it much more feasible to do this – the full size posters would have taken up too much of the wall space. I now have a much more constantly visible view of the spines than I ever had before when they were on bookshelves behind my desk amongst a lot of other material.

- The third biggest size posters have now been arranged on a sheet of white paper and placed underneath the plastic desk pad on which my keyboard and mouse sit and on which I write longhand on occasion. This provides an unobtrusive decoration and demonstrates the reproducibility of the electronic bookshelf. The picture below shows the framed electronic bookshelf posters, the version under the desk mat, the book PDF files and an opened file on the adjacent computer screen, and the iPad showing thumbnails of the same PDF files.

- The smallest size posters have been arranged in a 20 x 16in Wilko frame (see below) and given to my son and his wife as a housewarming present for the library area of their new house (not sure how much they will enjoy this but it had to go somewhere…!).

- The largest, full size posters have been stored at the back of a large picture frame that I have in my study (see Poster Management journey) in case I should want to use them in future.

In assembling the sets of posters as described above, I took the opportunity to vary the way the individual posters were displayed and to think about how they might appear on a large scale display or roll of electronic paper. Given that many arrangements are possible I included a tag line at the bottom of each one to identify the title of the collection (‘Col’) and the particular arrangement of that collection (‘Rig’). An example is shown below:

There is undoubtedly some synergy between some of the points that have emerged from this electronic bookshelf exercise and in the way that mementos might be displayed, and I intend to think about these when I start the next phase of the Memento Management work described elsewhere in this site. In the meantime, however, my current exploration of the Electronic Bookshelf has come to an end. Perhaps when electronic paper becomes sufficiently cheap, and when an App is available to create, manipulate and arrange the images of book spines and covers, I’ll attempt to replace my framed poster version with the real thing.