Having acquired a new iPad, I needed to transfer all my digital object collections from old to new tablet, so I decided to take the opportunity to explore the issues associated with a combined set of collections. I’m using the iPad Sidebooks app which provides a hierarchical bookshelf interface. A set of objects sits on a bookshelf. Each object can be either a single file or can represent a lower-level bookshelf containing either single files and/or objects representing even lower-level bookshelves. The Sidebooks app does display objects in an attractive visual way, and the iPad is a very portable and easy to open up and use in any setting. However, that doesn’t mean to say that it is necessarily the best place to combine collections. The following shortcomings need to be understood from the outset:

- Sidebooks can display digital objects, but many of the collections have objects which are only in physical form, for example, the stamp collection.

- Sidebooks is not the primary storage location for any of these collections (for digital items it is the laptop; and the physical items are located in a variety of places), so there is a danger of the Sidebooks version getting out of synch with the original.

- Some collections loaded into Sidebooks may be broken down into a limited number of named subsets for ease of comprehensibility and access, but the files in the original collection are not sub-divided in that way.

- For some collections (such as Mementos) only a subset of the objects is downloaded into Sidebooks; those items not in named subsets are simply not present.

Having said all that, the exercise to transfer a range of collection objects into the new iPad did provide an opportunity to think about the practicalities of Combining Collections. Actually, the word ‘transfer’ is not strictly correct; in fact, I just used the material on my old iPad as input to what needed to be loaded into the new iPad. Other inputs included the journeys I’ve recorded in this web site; and my awareness of other collections that I have. This examination surfaced the first issue associated with combining collections – Content. In some cases, it was difficult to decide whether to include a collection or not because of the personal nature of the material (poetry written in my younger years for example), and because the new iPad might be looked at by family members or by those inheriting when I die. I also experienced issues with the Mementos collection because it has hundreds of files distinguished only by facets in the index. To just include every memento file in Sidebooks would present the user with an amorphous mass. Instead, I wanted to have named subsets of material like the companies I worked for or the places I lived. However, this meant choosing a limited number of named subsets – and leaving out the remaining files.

Having decided what collections to include, I was now ready to start loading objects into the new iPad; but was immediately faced with Presentation issues: I know from my experience with my old iPad, that the top level in Sidebooks can look extremely cluttered making it difficult to grasp the totality of what is being represented – even if you are the owner and are familiar with the material. For other people – family or those inheriting collections – it must be an even bigger problem – see below.

Of course, it might just be the app. There are many other similar applications out there and they might do a better job. I shall certainly be looking into that in the later stages of this journey; and, of course, it may simply be better to combine the collections in the place they are currently stored – the laptop. However, for this exercise of moving to a new iPad, I’m sticking with Sidebooks; so, I needed to find a way to present the combined set of collections in a clearer way.

Of course, it might just be the app. There are many other similar applications out there and they might do a better job. I shall certainly be looking into that in the later stages of this journey; and, of course, it may simply be better to combine the collections in the place they are currently stored – the laptop. However, for this exercise of moving to a new iPad, I’m sticking with Sidebooks; so, I needed to find a way to present the combined set of collections in a clearer way.

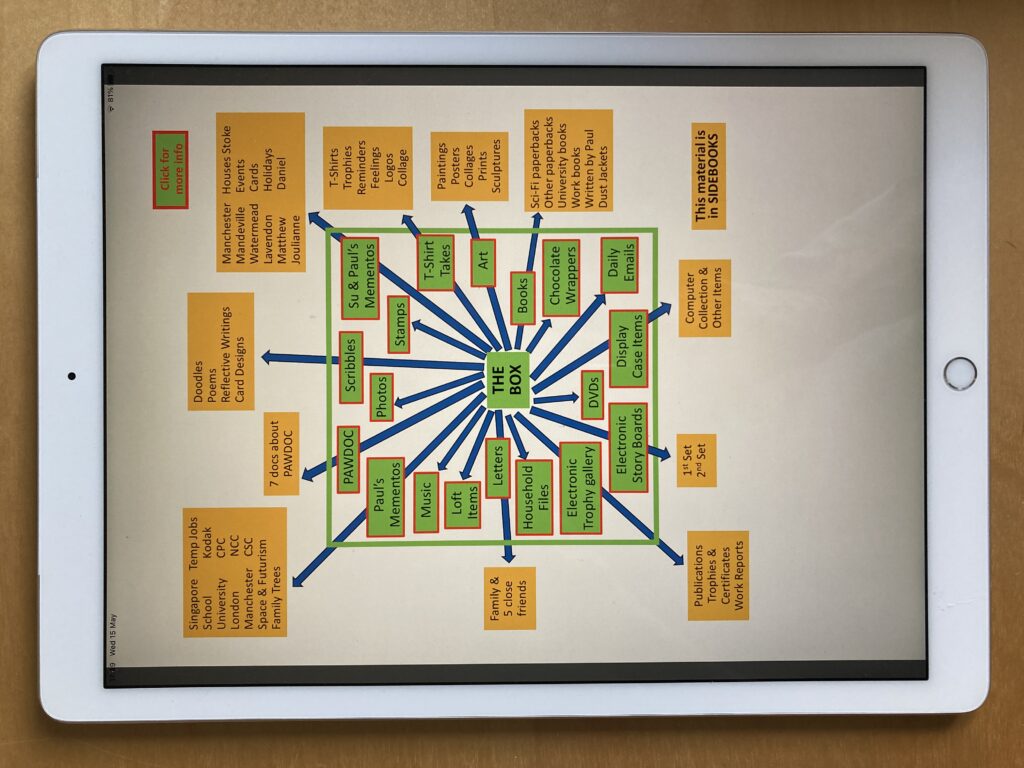

The solution I came up with was a PDF document with all the collections shown on the front page and with links to descriptions of each collection in the body of the document. This sits at the top level In Sidebooks with the front page showing. At the same level in Sidebooks are icons representing the bookshelves which contain substantive objects at lower levels in the hierarchy.

The PDF document also enables information to be included about the collections which are not suitable for including in Sidebooks such as the Stamp collection (I was able to include a list of the countries being collected and their status). I believe the PDF diagram makes things clearer – but it’ll be interesting to see if I have the same view several months down-stream.

The PDF document also enables information to be included about the collections which are not suitable for including in Sidebooks such as the Stamp collection (I was able to include a list of the countries being collected and their status). I believe the PDF diagram makes things clearer – but it’ll be interesting to see if I have the same view several months down-stream.

There was another reason for creating a front-end diagram of all the collections: to cater for the needs of other people (such as family, or those who inherit) who might encounter the material. It seems to me that there are three main characteristics which need to be catered for: first, people easily become overwhelmed and turned-off by large quantities of unfamiliar and apparently disorganised things; second, many people are just simply not interested in some of things that we ourselves are interested in; and finally, people will always want what they have not got; but once they have those things, while wanting to still have them, they lose a lot of interest in them. All three characteristics may affect how people feel about a combined set of collections. Therefore, I have chosen to call the PDF document ‘THE BOX’, and to list all the different collections in the box on the front page of the PDF, in an attempt to inspire interest, and to avoid overwhelming people (though I’m not sure this latter requirement has been achieved…) – see below.

The descriptive information within the PDF enables people who aren’t really interested in the named topic to get a quick idea of what’s in the collection without being overwhelmed by the objects themselves, thereby perhaps wetting their appetites to find out more; and once people become familiar with the contents of THE BOX, it may provide them with the confidence of knowing where the things they treasure are located. The idea is that THE BOX is full of unknown and interesting things and provides a quick way of finding out a bit more, and of documenting clearly what is where. Whether THE BOX succeeds in doing this is again something I may have more views on in a few months’ time.

With the rough design of THE BOX established, I started to load in the various digital objects associated with each collection. This is when I started to find other Content issues. In some cases, I had to make decisions about whether to include or exclude particular objects; for example, in my collection of Scribbles (Doodles, Reflective Writings, Poems etc) I decided to exclude school essays, but included designs for cards I made for particular people/occassions. In other instances, I revised how things were named and organised; for example, what was in the old iPad as a single set of ‘Paintings and Posters’ became a set named ‘Art’ subdivided into ‘Paintings & Drawings’, ‘Collages’, ‘Prints’, ‘Posters’, and ‘Sculptures’.

Another content-related issue was where an object can appear logically in two or more collections; for example, “The Meteor” – a book I self-published about parts of my stamp collection – can logically appear within both the ‘Stamp’ collection and the ‘Books I have written’ collection. This is an issue I had previously encountered in the Electronic Story Board journey, and is an inevitability with large collections of material. For small numbers of digital objects there is a simple solution: simply place a copy of the object concerned in both places. For larger numbers of digital objects, it may be best to provide links to the master version of the object concerned. The former is the only feasible solution in Sidebooks.

As I continued to load more collections into Sidebooks, I encountered a number of instances in which the Technical constraints of the Sidebooks app affected what could be included in the overall combined collection. Sidebooks only supports PDF files, so if large numbers of objects in a collection are stored in another format – Word or jpg for example, a large amount of effort would be required to convert them all into PDF to display them in Sidebooks. In the case of very wide spreadsheets even converting them to PDF wouldn’t work well because the conversion process would create page breaks across the width of the spreadsheet resulting in a PDF consisting of a series of rather disjointed pages. Hence, such technical issues create practical issues affecting what can be combined in a single overall space. Obviously, the more consistency that exists between the way the objects in a particular collection are constructed, and the technical requirements of the application which is to display all the collections, the easier it is going to be to create the combined collection. A prime example of this is when individual objects are given informative file titles, but it is subsequently decided to combine multiple individual files into a single PDF file to meet Sidebook’s requirements, for example. In this circumstance it is likely that much of the file title information will be lost.

The final issue I encountered was specifically to do with Physicality: some collections were simply not in a state to include in an overall digital combined collection. For example, the stamp collection consists of 19 physical albums. To digitise them would not only be too onerous, but the result would be out of date as new items get added. For these types of collections, THE BOX provides a perfect compromise in which some information can be provided without having to load in the actual objects themselves.

In summary, the main issues I encountered when trying to re-assemble a combined collection on the iPad, are to do with Content, Presentation, Technology, and Physicality. These are the topics that I shall pay considerable attention to when undertaking the next phase of this journey. And, for the record, the statistics associated with this initial attempt at an overall combined collection are: 19 separate collections of which 11 have objects in Sidebooks consisting of 2478 separate files taking up 22.6 Gb of storage.