Having explored the conversion of physical DVDs, engineered the delivery of the resulting files to the lounge TV, and experienced a few of the titles on its delicious 65-inch OLED screen, I set about deciding which DVDs I was going to hang onto. I ended up choosing to keep 20 of the 58 titles with the files totalling around 40 Gigabytes. One of my concerns when I started this journey was that the files produced would be too big to handle and, overall, would take up too much space. However, after adding this extra 40 Gb I still have 135 Gb of free space on my laptop which I consider to be sufficient for at least a few more years. The files themselves range in size from 670 Mb to 3.3 Gb – which is certainly very big; but at least there are only a few of them. In any case (I say to reassure myself) size is a short-term problem, as storage capacities continue to increase.

My rationale for keeping particular titles seem to fall into one or more of the following 5 categories:

- Watchability – productions that I can enjoy watching over and over again.

- Sentiment – productions that remind me of good times in the past or that I have a personal connection with.

- Spectacle – productions that are just awesome to watch with their extraordinary images and ambitious content.

- Instructive – productions that provide interesting and intriguing information.

- Music – productions that contain memorable songs or other excellent music.

This collection of files on my laptop would now appear to be a collection of my most favoured moving image productions; but, of course, it is not. They just happen to be the productions I particularly like in a set of DVDs that we just happen to have. A true collection of my favourite titles would entail trying to remember which items I have seen over the last seventy years that I liked best – an extremely challenging exercise. Finding and acquiring those items would probably be equally as challenging; nevertheless, it would probably be an enjoyable and rewarding hobby. However, I’ve never heard of anyone doing it in such a thorough way; only people who have collections of videotapes of a favourite TV series; or of DVDs. The reason is that moving image titles are dependent on modern technology – technology that is either transient like TV, or changing like cine/videotape/DVD. Books don’t have that problem: when people get a physical book, they can just keep it if they like it and they build up their collection of favourite titles over the years. Interestingly, the same has been true for physical DVDs. However, now that moving image has become a standardised software object, it’s possible that more people will gradually build up their collections of digital video files over the years. However, a physical book/DVD has a tangible presence in the world, whereas a software file is just about invisible. Furthermore, we now consume far more moving image material on a daily basis than we do physical books. These two distinctions means that our collecting habits associated with physical and digital media will never be the same.

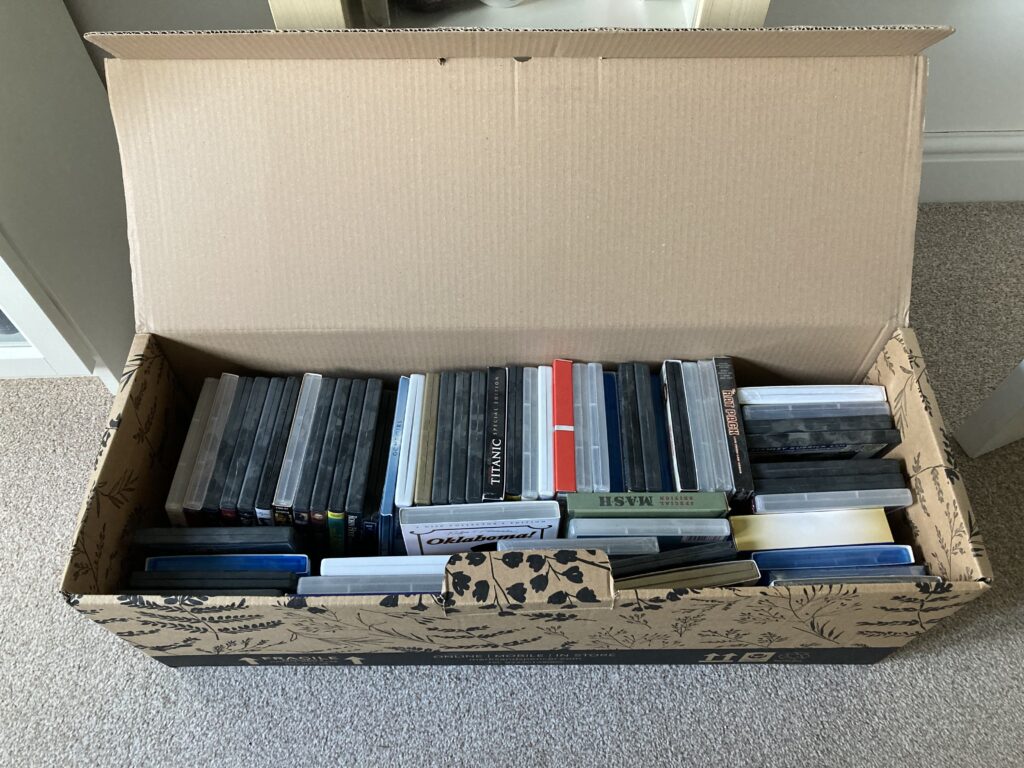

Following this line of reasoning, I think it unlikely that I will start to add extra items in the future to my new collection of moving image productions. I might include the odd item in the Videos folder if it comes along in the right format and I particularly like it; but I won’t be making special efforts to capture material I enjoy on a regular basis. The collection will stay pretty static over the coming years, and may or may not get dipped into occasionally. As for the physical DVDs from which I have created the software files, I will keep those packaged away in a box in the loft. Not because I will ever play them again, but because I want to have some proof that I did actually purchase the DVDs which I ripped to produce the files: it is certainly illegal to make a copy of a DVD you don’t own.