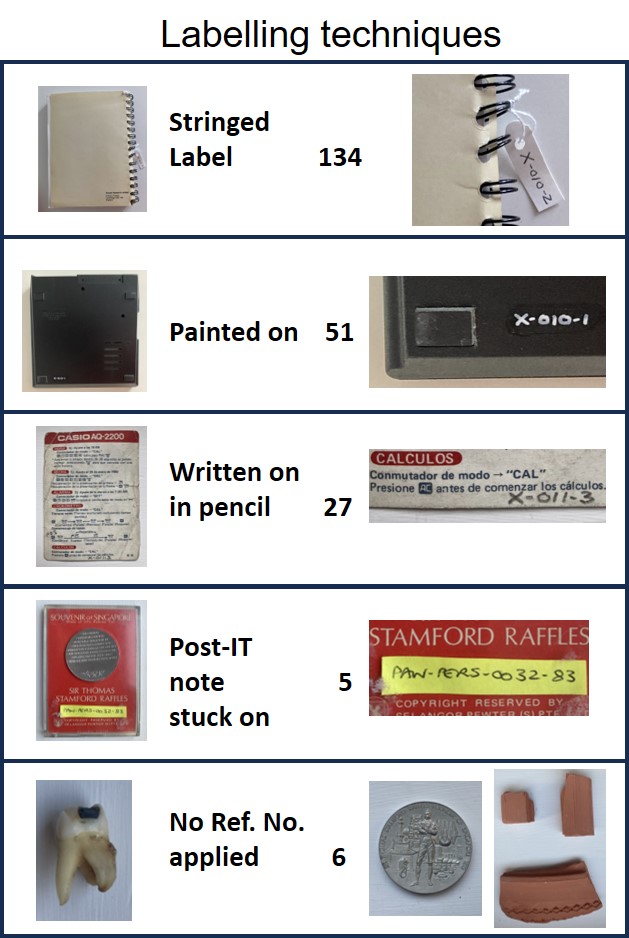

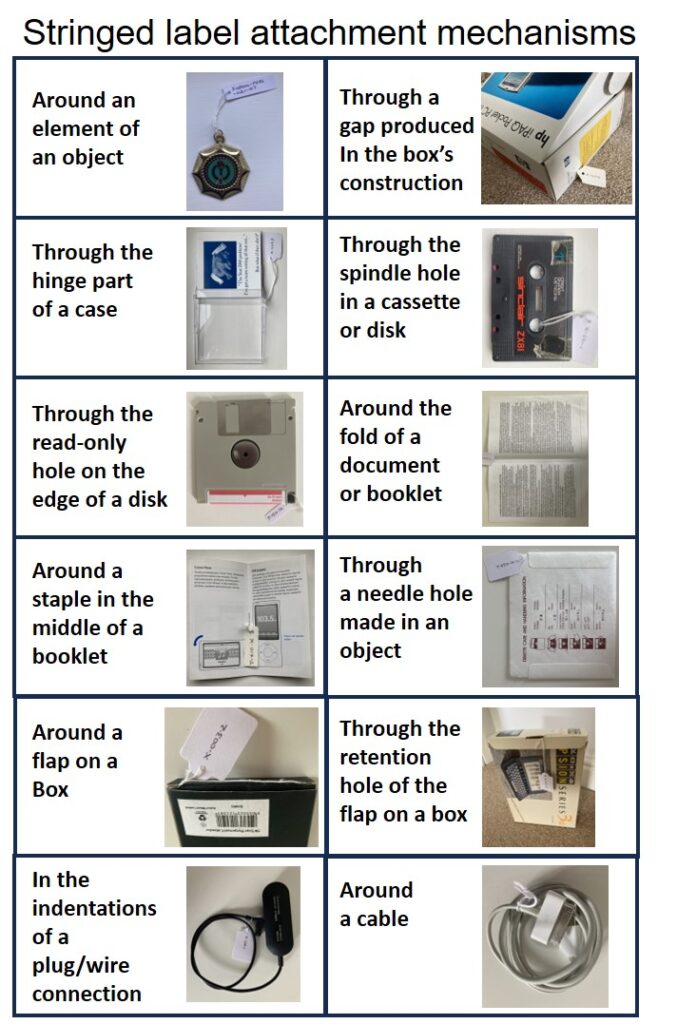

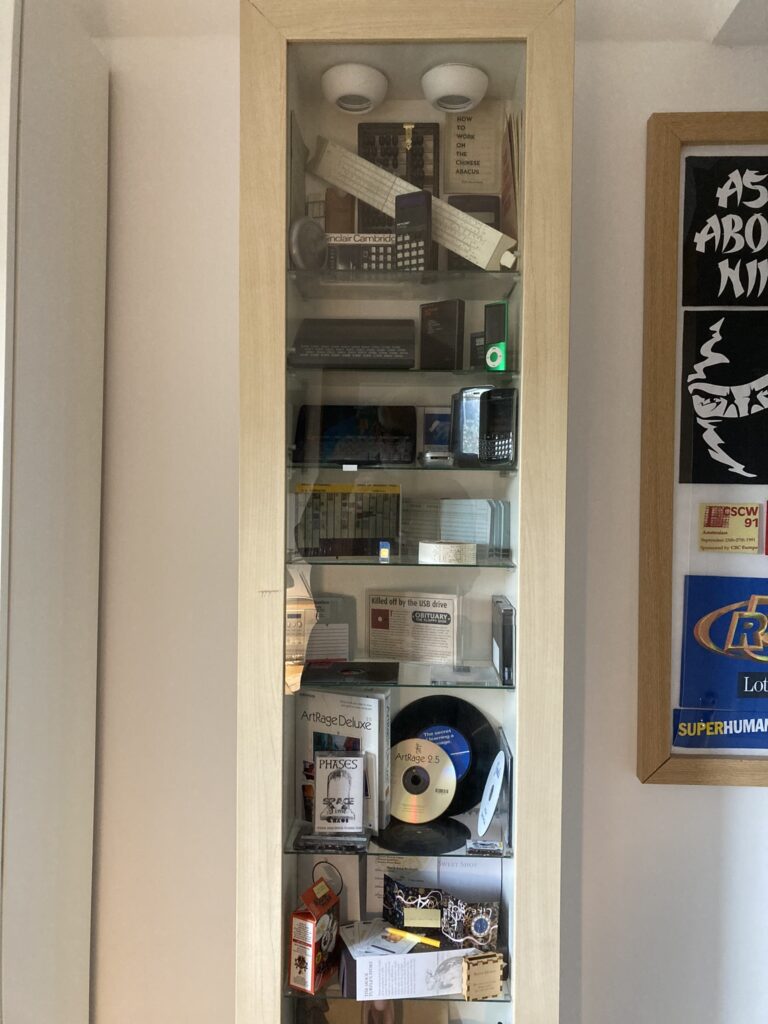

While I was cataloguing and marking the items in the display case collection, I took the opportunity to photograph each one. Not just a single photo; multiple digital images taken from different angles so that viewers could get a feel for all aspects of the object.

Of course, proper 3D images would have been preferable – but I don’t have the equipment or the focus at present: I want to get on with this journey and get the newly moved display case back in action.

Of course, proper 3D images would have been preferable – but I don’t have the equipment or the focus at present: I want to get on with this journey and get the newly moved display case back in action.

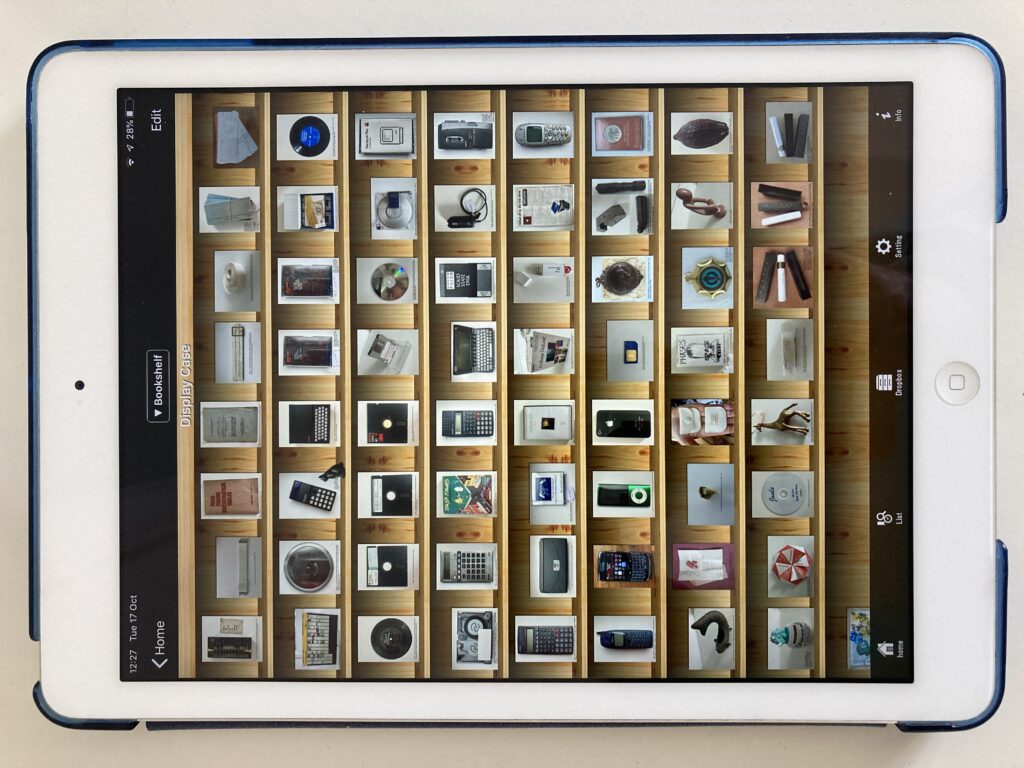

The destination for this digital version of the collection is the iPad app, SideBooks, which I have used to display objects emanating from many of the different OFC journeys, and which makes it easy to import files by providing a specific option to download from DropBox (a Dropbox account is easily set up and free to operate at a small scale). Uploading and downloading to and from Dropbox is very quick through a modern broadband connection. SideBooks displays the first page of multiple PDF files in a bookshelf format (with a selection of themes) which can be expanded or reduced to show more or fewer items accordingly, as illustrated below by a view of the complete display case collection next to a much-enlarged version.

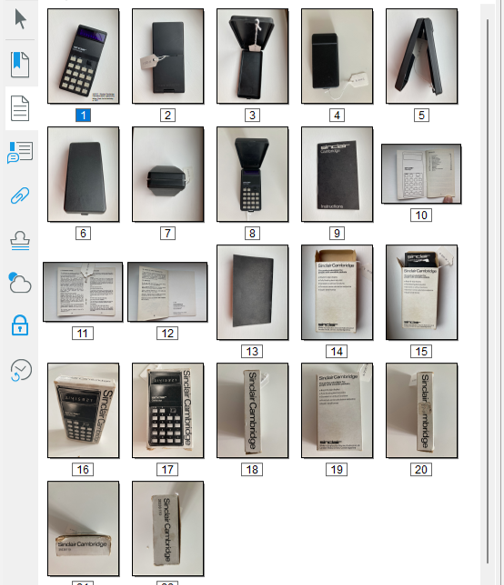

In this digital version of the collection, each item is represented only by a single file regardless of how many individual elements it comprises. For example, the Sinclair Cambridge Calculator is accompanied by a plastic case, an instruction booklet and the cardboard box it was packaged in. Multiple images of each of these four items are all contained in a single PDF file, even though they are each individually catalogued and indexed. This is achieved by assigning an overall reference number to the set of related objects (X-002) and by assigning sub-reference number to each object: X-002-01 for the calculator, X-002-2 for the plastic case, X-002-3 for the instruction booklet, and X-002-4 for the cardboard box. Each of these individual items has its own PDF file containing the relevant set of photos, and these are the master digital files associated with the index items. However, for the purpose of the digital display in SideBooks, all the images contained in each of the four PDFs are collected together in a single PDF file titled “X-002 – Sinclair Cambridge Calculator which I gave to my father, Fred, for his birthday in 1977.pdf” as shown below.

In cases in which an object has no associated elements, there is no need to use sub-reference numbers, and the same PDF file can be used as the master digital file and the file for display in SideBooks, for example “X-019 – Blackberry Bold 9700 similar to the one I started to use in CSC in 2009”.

This approach to indexing has been specifically designed to accommodate the capabilities of the digital display application that I am using – SideBooks. If some other mechanism is used, an alternative design may be appropriate. SideBooks enables individual items to be selected and then for each page of the PDF file to be leafed through. Consequently, each photo has been given a separate page in the PDF file. Some brief information about the contents of each PDF is provided at the base of each of the first photo in each file. A more thorough approach might label every photo in every file, but I didn’t think there would be sufficient benefit to make it worth the effort. A more worthwhile exercise would be to provide a short narrative for each object, telling the story about what it is and how it came to be in the collection. This could be provided on the second page of each PDF; and perhaps also delivered as a spoken word sound file which could be selected and played. Such a sound file might also be used to augment the physical display if viewers were able to verbally request that it be played – “Alexa, play X-019”.

It’s worth noting that the physical display case used to present objects in this collection is too small to accommodate all the items at once; whereas the digital display mechanism can display all the items. This is the obvious but significant difference between physical and digital displays of larger collections: all items in a collection can be made accessible digitally, but may be too great in number to be presented physically to the viewer. Having said that, ordering the presentation of items in a digital display may require further effort. SideBooks presents files in the alphabetical order of their file names, which, in this collection, always start with the Reference Number. However, the allocation of Reference Numbers is random; the next item gets the next available Reference Number. Consequently, the items of this collection were somewhat mixed up when the files were presented in SideBooks, whereas I wanted to have all the computer-related items together followed by all the personal items, and ending with the items associated with our visits to four special restaurants. To achieve this ordering, I added a further set of numbers to the beginning of the filenames in Sidebooks, for example, “X-019 – Blackberry Bold 9700 similar to the one I started to use in CSC in 2009” became “SB42: X-019 – Blackberry Bold 9700 similar to the one I started to use in CSC in 2009”. The need to add such numbers is a little irritating, but necessary with this particular digital configuration. SideBooks does allow searching of the filenames – but this can only be done across all the different collections in SideBooks, which, in this case includes many hundreds of mementos, books and papers; and I don’t believe it alleviates the need to deliberately order the digital presentation of the objects.

The ability to have the whole collection on hand in the highly portable iPad is a great advantage – especially when it comes to wanting to take a look at items that haven’t been viewed for many months or years. The sheer accessibility of this combination of slim and lightweight tablet and highly visible software interface, provides a very useful and useable way of keeping a handle on what is in a collection.