My colleague, Clive Holtham, was instrumental in putting me in touch with suppliers who loaned me a scanner and document management software around 1995, to enable me to progress my mission to understand how personal electronic filing would work in practice. Some six years later, in February 2001, Clive and I met up for dinner and a catch up on what we’d both been doing. I explained that as well as scanning new hardcopy as I acquired it, I was also trying to scan all the legacy documents I had acquired since 1981, when I started this electronic filing adventure. Clive pointed out that it would be interesting to see what I thought of each document in retrospect, as I carried out the scanning process. After all, the point of indexing and filing the documents, was based on the assumption that some of them would have some value downstream. Here was an opportunity to get an insight into what their downstream value might be.

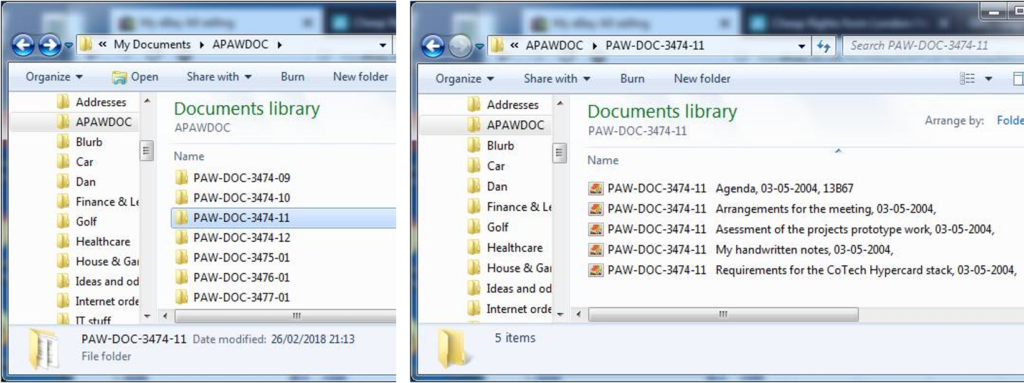

I took Clive’s suggestion on board towards the end of 2001; but, to minimise the effort required, I decided I would only comment on those documents which prompted some particular thoughts. The comments would be recorded at the end of the Title field in my filing index; and they would be identifiable by being placed within a special set of characters in the following format: <<! Date: Comment Text here !>>. To make it easier, I created a script in my Indexing software to automatically place the delimiter characters with current date at the end of the title field, and assigned it the keyboard shortcut CTR-8. This seemed to work in practice, and I got into the habit of making my comments in real time as they occurred to me. After a while, I started to use the facility to record other information, such as a document being duplicated in another Index entry, or problems I had had with scanning a document. Now, in 2021, 20 years after starting to record these comments, I find that 584 records within my filing index possess such comments; and 20 of those have two comments.

This is an analysis of what those comments say. They have been placed into one or more of 5 categories:

- Comments on the impact of the material (7% of the 584 records with comments)

- Comments on the contents of the material (32%)

- Comments which prompted questions and thoughts (23%)

- Comments about memories forgotten and/or remembered (17%)

- Comments about filing, indexing and scanning activities (46%)

The full list of comments and the categories to which they have been allocated is provided in this link. The comments have been further allocated into sub-categories which are used in the discussion below. However, the following two salient points need to be born in mind when considering the results of this investigation:

Scale: Although 584 records with comments may sound a large number, in fact comments have only been made on a small subset of the contents of the filing system: 584 is only about 3% of the 17,350 records in the index. This could indicate that the sample size is too small to be generalised; though, I believe it is more likely to indicate that relatively few documents merited a comment. Unfortunately, there is no data to investigate which of these two possibilities is the case – the decisions to include comments were made in an arbitrary manner over many years.

Lag: The time between a document being included in the filing system and when a comment was made about it, has almost certainly affected many of the comments. Presumably, the more time that passes, the less likely the contents of a document are to be remembered, and this may make them more remarkable when they are encountered again. The actual lags that occurred have been calculated as a number of years by the difference between the Creation Date field in the Index, and the date recorded at the beginning of each comment. This shows that over 93% of the comments were made more than 10 years after the documents were included in the filing system; and over 50% had comments with a lag of over 20 years. Only 12 items had comments with a lag of less than 5 years.

Comments on the impact of the material (43)

These comments include remarks about documents which have influenced my thinking (8). For example, “This is a most important paper because it alerted me to the key insight that to get the most out of an OA investment the organisation must change the way it does business”. A further 9 comments relate to documents which were more generally important to my work, for example, “This was an important edition of EDP analyser and highly relevant to NCC’s OA team of which I was a part”. Finally, 26 comments were made about documents that are special in a variety of other ways, for example, “This is a great example of how to do brainstorming”, and “This is an interesting document to have from the early days of the net”.

Comments on the contents of the material (188)

Just over a third of this category is concerned with comments about a document I wrote or activity I was involved with. This is hardly unexpected given my intimate relationship with the events. For example, “Have just read the suggestions I made to Esprit about its CSCW program. I wonder if they made any kind of difference”; and “This was my one not very successful claim to broadcast fame – and I’m not even sure it got broadcast”. A quarter of the comments just remark on ‘interesting content’, for example, “This is a fascinating article because it represents a twilight period in the change from old style typists to individuals doing the typing all themselves”; and “This was worth another read – definitely food for thought…”. The remainder include comments in a range of other sub-categories – listed below together with an example for each one.

- Comments on technology developments (16) – “Seems very advanced for 1978”

- Assessments of predictions (8) – “The prediction of a day in the life of the CEO in 2013 didn’t get it quite right”

- Comments on the author or other people (8) – “I’ve been thinking about getting in touch with X again”

- Comments on photos in documents (7) – “While scanning this I discovered that it contains a photo of X”

- Content which I thought I might find useful (26) – “This document is highly relevant to the assignment I am about to start”

- Comments which provide a critique of content (5) – “I think this process missed out the key element of Improvement by Learning by Doing”.

Comments which prompted questions and thoughts (135)

The majority of these comments – some 60% – were general reflections and musings prompted by the documents concerned. For example, “I think it demonstrates that prior to the internet and the web there was a different way of thinking about information: in those days having the information meant having the actual item, whereas today, in the internet/web/mobile era, having the information is all about having a device and knowing where to look”; and “It would be interesting – amazing – to re-run this event with the same people”. The other six sub-categories are all specific questions:

- Is this still around/available/the case today? (10 comments – for example “I don’t hear the term ‘Groupware’ much these days – I wonder if it has fallen out of use”

- What’s a person doing today? (15 – “I wonder If X is doing anything related to this now – haven’t seen him for about 20 years”)

- Is this still relevant today? (12 – “This might be interesting to read to see if 25-year-old advice about dealing with Info overload still applies”)

- How does this look in retrospect? (4 – “There was a big fuss about X’s thinking on this – would be interesting to see how it all looks in retrospect”.

- What was the impact of this? (5 – “This work on Teletel was ground breaking and was subsequently successful. How it affected the French use and take-up of the web I don’t know”)

- How did these predictions fare? (6 – “The Booze-Allen Hamilton report was very influential. It would be interesting to see how its predictions fared”)

Memories forgotten and/or remembered (100)

70% of these comments are about things I’d forgotten either partially or wholly; and 30% about things I remembered about associated aspects, or about people. Examples of each are provided below:

- Forgetting something about a document or a related activity (28 comments), for example, “I’d forgotten these details and didn’t know I had these notes”

- Forgetting about the document or activity all-together (41): “Can’t remember giving this talk”

- Remembering associated aspects or it prompted memories (19); “This was a pioneering machine – we really liked the Snake game, and the early type of remote access mail through the phone lines was relatively quite advanced”.

- Remembering the author/other person (12); “That’s a name I haven’t thought about for years! – think I met him”

Filing, indexing and scanning activities (266)

Over a third of all these comments concern filing practicalities – not an aspect which was envisaged when I established this comment facility. Recording information about the operation of a filing system is definitely an overhead, so there is a natural tendency to minimise the effort spent on it. Consequently, the fact that it was quick and simple to create comments in a form which was tightly coupled with individual documents and their index entries, made this facility an obvious choice for quickly documenting issues or important observations. The 22 separate sub-categories of comment listed below together with an example for each one, illustrate the extensive range of topics that were encountered as the PAWDOC collection grew and aged (note that over 93% of these comments were made at least 10 years after the document concerned had been included in the collection).

- Practicalities of using PAWDOC (5) “Must force myself to search for stuff even if I don’t think it’s in this index!”

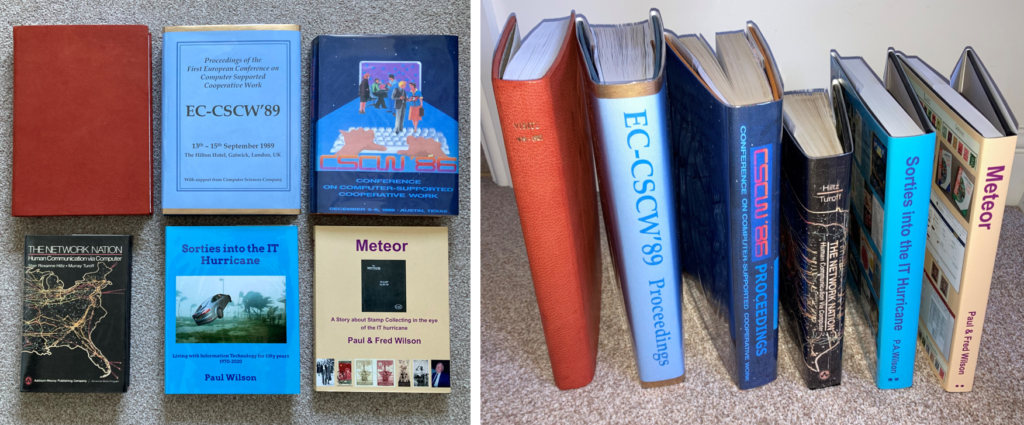

- Deciding what to include/remove (5) “Artefact removed for inclusion in PAW personal collection”

- Notes about where items originated (6) “The Quick Reference Card was included in Nov2018 when I found it inside the WGEM starter pack”

- Notes about what version is filed (8) “This Aug86 version must have replaced an earlier version in my collection”

- Notes about artefacts (6) “Specified this as an artefact at this late date because it’s the first issue I have in this new format”

- Notes about cross-references in the collection (7) “See also PAW/DOC/0110/145”

- Notes about duplicates in the collection (87) “Some of these documents are duplicated in PAW/DOC/7971/01”

- Notes about Archiving (6) “This was in an archive box but archive status had not been specified in the Movement field”

- Comments on Reference Number (16) “This document has the number PAW/DOC/0005/03 at the top – but that number is for something else”

- Comments on Title field (9) “Inserted the info about the abstract when I was scanning because there was no reference to it in the title”

- Comments on Creation date (12) “Don’t understand how the date on this paper is 1986 but the record was created in 1984”

- Comments on Publication date (3) “2019 properties of the word doc say this was modified on 31May1985 so this was probably the publication date”

- Comments on Movement field (10) “Don’t know why this says it was scanned and paper destroyed in 2004 – in Feb 2006 there was a full envelope of material in the box”

- Losing/deleting index information (4) “I deleted the title text of this accidentally when scanning so this is a replacement title text”

- Lost or misplaced documents (17) “Found the electronic version of this filed in FISH under PAW/DOC/4052/01”

- Relationship with Personal files (8) “I found these PAW/DOC papers in one of my personal home files”

- Notes about physical characteristics of items (17) “This printout had almost completely faded so it was a challenge to see if the scanner would bring the text to light – and it didn’t do a bad job!”

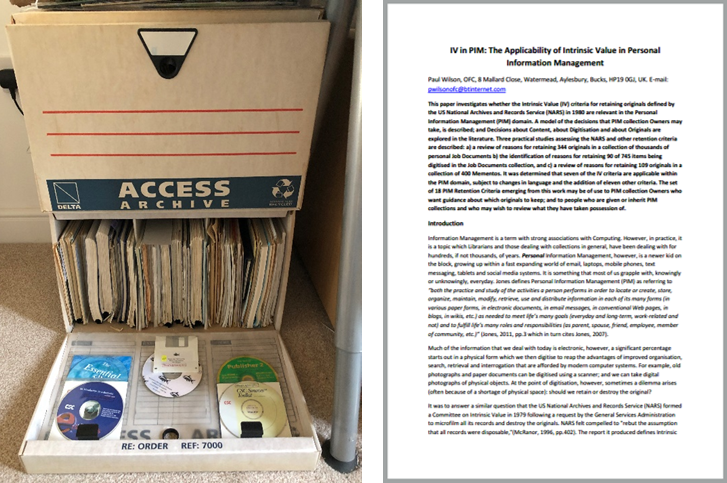

- Notes about disks in the collection (6) “This included a disk containing a DOS version of the ITSforGKProposal”

- Management of the FISH DMS (8) “This seemed very necessary at the time when disk space was short – and very complicated. Now in 2006 with 40Gb on my PC it doesn’t seem to be an imperative at all”

- File formats & Digital Preservation (7) “No longer able to read the floppy disk when it came to take this material out of archive to scan it in 2006”

- Notes about loading electronic files to FISH (17) “The Word version doesn’t have the appendices so I PDF’d the Word version and then scanned the appendix pages from the hardcopy. Unfortunately, the pagination of the Word document is slightly different from that of the hardcopy – but the words are all the same”

- Notes about Scans and Scanning (49) “These pages were too thick to go through the duplex scanning process so I had to do one side first and then the other side”.

Conclusions

No great revelations have emerged from this investigation. However, it’s clear that reviewing old material in this way provides an opportunity to reflect, and perhaps to rediscover potentially useful material. These are luxuries that are hard to come by amidst the pace of modern life. Whether such activities actually provide any tangible benefits is hard to say: I can’t remember if any of the rediscovered documents made a difference in my subsequent assignments; and the benefits of reflection are difficult to pin down at the best of times (though I personally feel it is always worthwhile).

The one practical finding that has emerged from this exercise is that there are significant advantages in being able to quickly and easily annotate a filing index with any relevant additional information, be that extra detail about content, or factual information about the way that content has been filed. The former augments the information provided by the filing system, and the latter assists in its smooth operation. In fact, the latter is more than a mere nicety. My experience has shown that, as this type of personal filing system grows and ages, the number of imperfections it possesses increases substantially. The long list above of sub-categories of ‘Filing, indexing and scanning activities‘, and their associated examples, provides an indication of the range of issues that can arise. Having the ability to quickly note details of those issues in a place where they are likely to be immediately visible to the user, is of great benefit.