It’s been nearly a year and a half since the simulated Electronic Trophy Gallery was completed and hung on my study wall. Since then, I may have looked at it seven or eight times – certainly not a great deal more: I’ve had no special need to consult it. Perhaps, the main prompt to inspect it has been to establish if a particular item has been included – and I’m pretty sure that there was one occasion in which I determined that a deserving candidate wasn’t there. Herein lies one of the shortcomings of the simulation: to include an extra item would require substantial effort to redesign the PowerPoint images; and to reprint the dual A3 pages, match them up, and get them into the frame so that they look a relatively seamless poster. A truly electronic system would be considerably easier to add in new items – which is certainly something I need to be able to do. For example, I self-published a book earlier this year entitled ‘Meteor – A story about stamp collecting in the eye of the IT Hurricane’, and that certainly deserves a place in the Gallery.

Despite this difficulty, the simulated Electronic Trophy Gallery has substantial advantages. For example, when I decided to write this evaluation piece, I stood in front of the frame and picked out an image of a rugby cap labelled A19. I picked up my iPad, opened SideBooks, found the section on ‘Paul’s Trophies & Certificates’ and selected A19. The cap appeared in full technicolour. Subsequent pages displayed it at different angles, followed by, to my surprise, some pages in The Mountaineer (the magazine of my school, Mt. St, Mary’s College) with descriptions of some of the games with my name mentioned twice, and the final page recording that Full Colours that year had been awarded to S.J.Bolger, P.A.Wilson, and A.Maggiore: that was what the cap was for. This was a most pleasing collection of goodies to find, particularly as it was so easy to get at. Had I really forgotten those pages were there? Well, yes. There are over 200 items represented in the Trophy Gallery and I can’t remember every page that I assembled as I constructed the iPad version of the Gallery a year and a half ago.

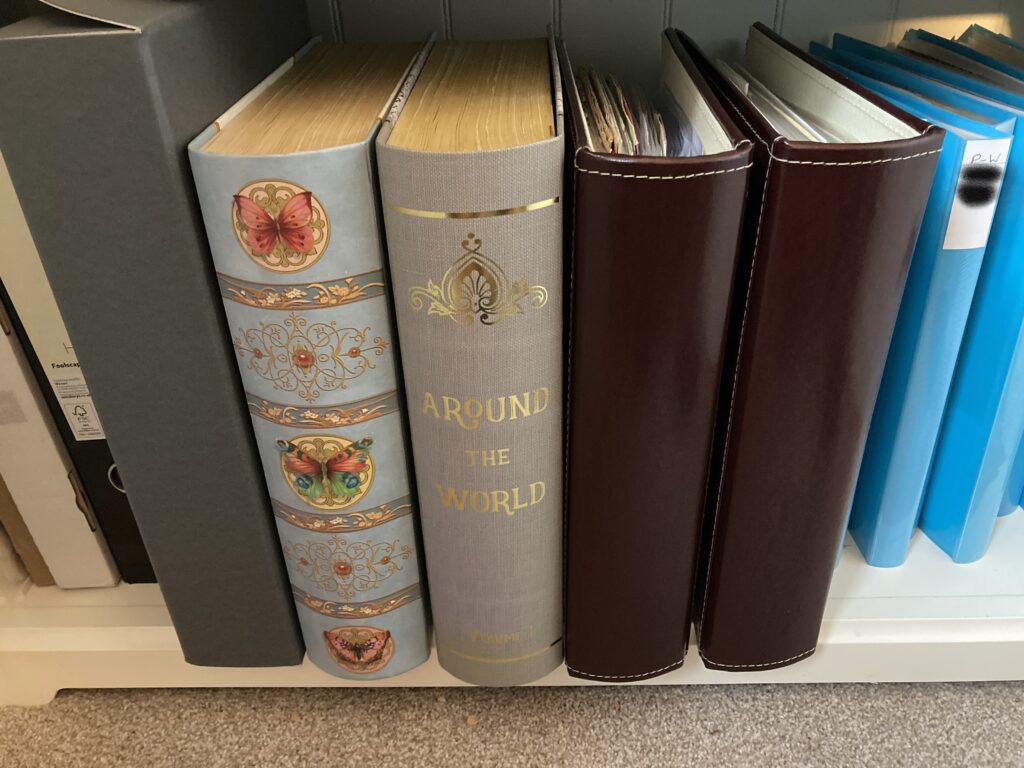

I looked up some of the other items in the Gallery. Some had just the images (like the front, spine and award plate of the Black Beauty book I got as a class prize at school); whereas another contained the text of a conference paper I gave together with the preface by the conference chairman and the contents of the whole book of proceedings.

It is the immediacy of being able to open up items on the iPad, and the ability to find more information about an item so quickly, that is the most striking aspect of this installation. If I had to choose between the physical artefacts and this simulation, I would say that you’re asking the wrong question: It would be totally impractical to assemble all this material and their adjuncts in the physical space in my study. This simulation is the only way it would work unless you had a very large house, lots of money, and access to presentation specialists. A more appropriate question would be whether I would be prepared to destroy all the physical artefacts and make do with just the digital versions? The answer to that is ‘yes’ for some things and ‘no’ for others. Some things, such as the trophy I won for winning a pool competition in a hotel while I was on holiday, was destroyed long ago; however, the physical books, journals and magazines in which my writings appear, are all stored away in a bag in the loft – relatively inaccessible but still in existence.

Am I likely to look at the Gallery very much in the future? Well, no, I don’t think so. But that’s not really the point. Having it there is the important thing. Knowing it’s there, containing a complete set of the things I regard as trophies of my achievements, and being available for access whenever I so desire, is the value afforded by this installation.