The uncertainty and confusion reflected in my previous post were dampened down a little as I finished assessing each item to decide if it should live or die, and started to move those items earmarked for survival into their new binders and boxes (more of those later). To remind you, the main driving factors in this exercise are the need to make space; and the need to move the retained objects into loose leaf storage containers that won’t fall over. This first stage has been looking at mementos; the second stage, which I shall start once I’ve finished this interim debrief, will be looking at letters, cards and other such missives.

I started out by building a spreadsheet to record my thinking, and developed it over the first few objects I looked at. It ended up with some 22 headings intended to fully document my reasoning about why an object was being kept or obliterated. The first objects I considered were two prayer books and a hymn book which were with me through eight years of boarding school. I’m no longer a church goer, but these books and I have history; so, it was a good test to get stuck into the process. I ended up choosing to destroy the three volumes, and the spreadsheet suggests that I did so primarily because a) I had no use for them, and b) they were dirty and torn. How did I feel afterwards? The spreadsheet records ‘Should have done this long ago’.

With this positive start in my drive to make space, I embarked with some confidence upon assessing the 285 Ref Nos with physical items in my Memento collection (the other Ref Nos exist only in digital format). The first thing I did was to go through the index and identify those items that I definitely wouldn’t get rid of and designated them ‘Not a candidate’. I reasoned that there was no point in going through a time-consuming analysis process if obliteration just wasn’t on the menu. This eliminated 140 of the 285 items. Next, I identified those items that were not stored in the plastic wallets or presentation folders in my study cupboard. There were 28 of these stored in various places such as the loft, display cabinet, bookcases, chest, and frames on the wall (our lives are rarely straightforward….). I then used the spreadsheet headings to analyse the remainder; but the result was disappointing – I ended up by only destroying 27 items – about 10% – a meagre amount compared to the 41% of original items that were excluded from the collection in the first place when it was being assembled; and the 69% of those that were included in the collection, being destroyed and retained only in their digital form. Given that perspective, my latest attempt eliminated relatively few; but perhaps it simply underlines that the previous sorting had truly separated out the items I really wanted to keep? After all, it wasn’t as though I had breezed through the exercise. I had had to think hard about each object, and, as the exercise went on, I found it harder and harder to understand why I was keeping things – but, for the most part, keep is what I decided to do. In the end, I came back to the obvious conclusion that these were my objects and therefore I could decide to do whatever I wanted with them. Other considerations such as what would happen to them after I’ve gone, or whether the family or, indeed, the world, would have an interest in them, were peripheral.

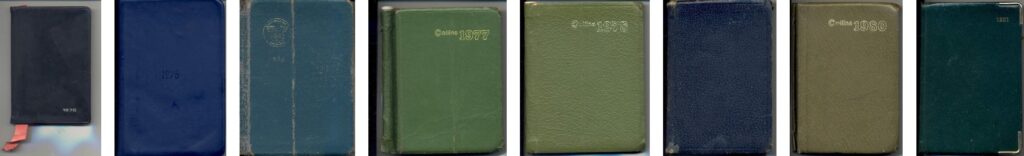

Interestingly, there were 12 items which, despite either being initially categorised as ‘Not a Candidate’ or which the analysis process had designated as ‘Reviewed and retained’, were eventually obliterated in the final stage of moving them to the new containers. Eight of them were pocket diaries which one would have thought would have been prime candidates for keeping; but, no, I realised that they are far easier to access and read on the screen, and they are highly inconvenient shapes to store in quantity. They went.

Eight of them were pocket diaries which one would have thought would have been prime candidates for keeping; but, no, I realised that they are far easier to access and read on the screen, and they are highly inconvenient shapes to store in quantity. They went.

The other four items were two long newspapers articles, a spoof issue of The Times, and a self-help booklet on managing one’s time – all of which I eventually concluded I would never, ever, read again. This whole experience seems to suggest that, while there is a bedrock of basic criteria and feelings that apply when an individual is deciding to keep or obliterate, it is, nevertheless, always a little pliable around the edges.

This whole experience seems to suggest that, while there is a bedrock of basic criteria and feelings that apply when an individual is deciding to keep or obliterate, it is, nevertheless, always a little pliable around the edges.

One other observation came through strongly in this exercise: the decision to obliterate is much easier to take if a scan of the object already exists. I had already scanned every item when I organised the collection in 2014, so there was no work to do in any of these obliterations: the object still lived on in the digital world whatever I did to it in the physical realm (as testified by the above pictures).

Regarding the act of obliteration, I discovered that my primary concern was to ensure that, when it was in the recycling bin, it was clear that it was done with: I wouldn’t have wanted the opportunity to reconstitute it myself, nor for anyone else to think it was still current. This was usually achieved by tearing the paper into four or eight pieces. I had no desire to completely obliterate it (that would have taken far too much effort): I just wanted to put it into an ‘out of action’ state. I suppose objects do get reconstituted after being merely damaged – but not the material I was obliterating. The few tears did the job. Those items will never be the same again.

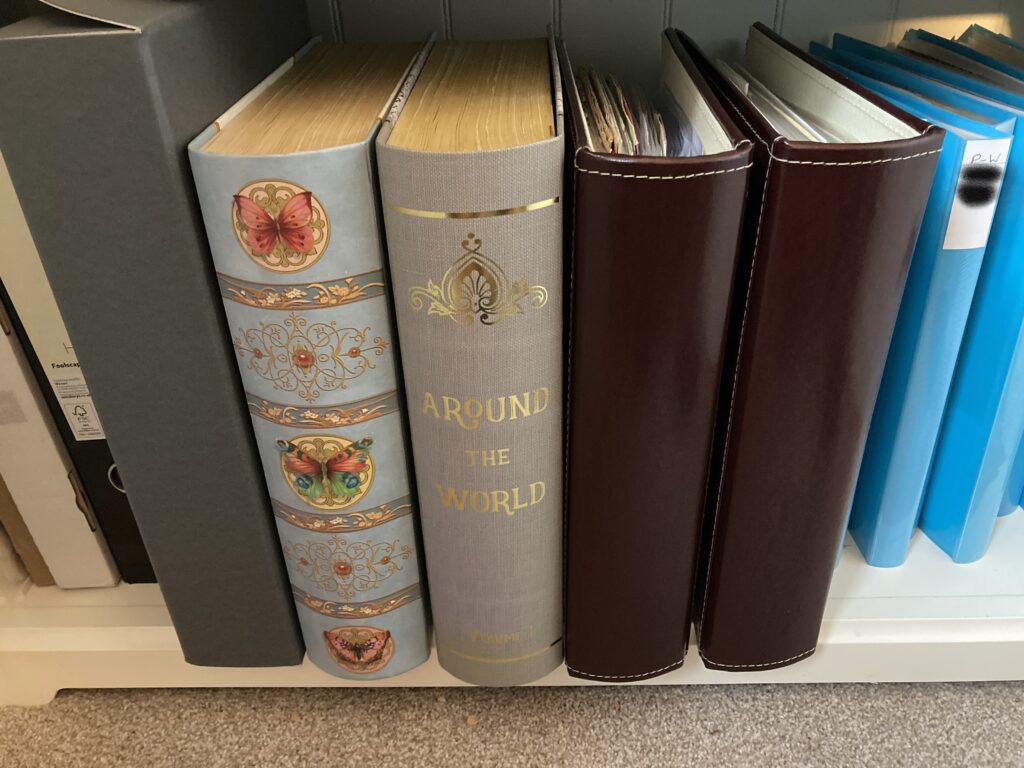

Perhaps one of the most interesting observations from this exercise was that, as I moved the collection into its new binders and boxes, I perceived it becoming much more organised and accessible, and, concurrently, worthy of a comprehensive index – perhaps with an accompanying precis of the events represented by the collection’s objects. The leather ring binders and the accompanying plastic wallets of varying configurations (single pocket, 2 pocket, 3 pocket, 4 pocket, 8 pocket etc.) all came from a company called Family Tree Folk. The binders are good looking and spacious and will make it easy to look through the thinner material housed in the plastic folders. I also acquired a sturdy clamshell box from the same organisation. Together with a couple of box files that I already had (the Butterfly and Around the World boxes in the picture below), these containers house the thicker material such as booklets, magazines, phone directories etc..

The box containers are so much better than the plastic wallets that flopped about on the bookcase shelves, and provide much easier access to their contents. However, inevitably it’s the leather binders that will get flicked through, and the boxes will remain opaque repositories of hidden objects. I mused about how references to those objects could be included amongst the leather binder pages, and then realised that this was really just a sub-plot to the bigger problem that all this stuff is tucked away and rarely looked at. I should really apply my own OFC mantra – to use and exploit the objects that one keeps. I’m not sure what I’m going to do yet – but the whole question of bringing this material to life is certainly on my mind.

The box containers are so much better than the plastic wallets that flopped about on the bookcase shelves, and provide much easier access to their contents. However, inevitably it’s the leather binders that will get flicked through, and the boxes will remain opaque repositories of hidden objects. I mused about how references to those objects could be included amongst the leather binder pages, and then realised that this was really just a sub-plot to the bigger problem that all this stuff is tucked away and rarely looked at. I should really apply my own OFC mantra – to use and exploit the objects that one keeps. I’m not sure what I’m going to do yet – but the whole question of bringing this material to life is certainly on my mind.

Going back to my original objective of freeing up some bookshelf space, I think that’s a bit of a lost cause. I have undoubtedly thinned the collection down a bit – but the improved containers have taken up a lot of that extra space. However, I’m going to have to live with that as I don’t fancy going through yet another painstaking analysis and selection process. Perhaps the letters which I’m going to tackle next will be a more fruitful culling field.