I haven’t investigated Personal Task Management in this blog, mainly because, being retired, I don’t have anything like the number or intensity of tasks as I had at work; so I don’t have the raw material to undertake an investigation of the subject. However, in starting to write about Liz Davenport’s book ‘Order From Chaos’, I realised that this is also an opportunity to document some of my own experiences and thoughts on the topic so I’ll weave them into the rest of this write-up.

Davenport’s book, subtitled ‘A 6 Step Plan for Organising Yourself, Your Office, and Your Life’, is certainly worth reading by anyone who has a real desire to organise their work. I say ‘real desire’ because, as the subtitle suggests, there are no half measures here. For Davenport’s approach to work, it’s necessary to plan and manage all one’s work through a Filofax-type loose-leaf notebook which she refers to as the Air Traffic Controller. In a preparatory phase, the desktop and office surfaces are cleared, unnecessary paperwork and materials are discarded, and the filing system is reorganised. This lays the groundwork for setting up a schedule for all existing tasks – both short and long term – in Air Traffic Control. Then, guidance is provided for how to manage all incoming information and communications – either to deal with them immediately or to schedule a task and file the paperwork. Finally, there are descriptions of how to plan and end a working day. It all makes sense and is described clearly. However, this is super-efficiency at work, and will probably require a considerable amount of discipline to achieve. I know I’ve met many people who are just not that way inclined.

The book was written in 2001 at a time when PCs and laptops had just become prevalent in offices, but email volumes were substantially lower than today and mobile phones had not yet become widespread. Consequently the book talks mainly about paper, though the pros and cons of electronic organisers are discussed (Davenport says she does not recommend the electronic systems yet as, at that time, paper was still quicker, simpler and more reliable). [I subsequently emailed Liz Davenport and asked if this was still her view and her reply was, “Sadly, paper is still faster and simpler. Most folks keep their appointments on their phones now but the whole “TO DO LIST/NOTES” aspect is still best served with a paper system because 99% of folks won’t take the time to put tasks and notes in their phone so it goes back to piles, post-it-notes and remembering and we know how effective that method is!”]

There are small sections advising on how to deal with email and which suggest setting up your computer filing system to mirror your paper filing system. It would be interesting to know if the rise in mobile phone usage, email volumes and the emergence of social media, have affected Davenport’s views [In response to my email asking this question, Liz Davenport replied “Not really because the basic 6 steps still apply, there’s just a higher amount of stuff in each step. Doesn’t mean there are more hours in a day. LOL!”]

The core of the book’s approach is Task Management – how to identify, agree to, schedule, and record tasks. Everything else in the book is designed to help you manage tasks and get tasks done. For many people, this comes down to having a To Do list (I used to create one every working day before I retired) ; but this goes way beyond that. The book instructs that all incoming communications and requests for action should be dealt with there and then or scheduled for some later date. It also advises on how to say No when new tasks are offered (even suggesting that if the boss wants you to do something that you haven’t got capacity for, you should ask which of the other things in your clearly documented schedule should be given lower priority). Rescheduling is permitted, but, if a task has been rescheduled 5 times, it is unlikely to ever get done so just cross it off the list. Based on this complete list of scheduled tasks, a plan for the day’s activities based on all scheduled appointments and prioritised tasks, should be drawn up before doing anything else; and the full schedule and associated notes should be written down in the Air Traffic Controller which should be fully visible on the desk at all times. Interestingly, I did experiment myself with keeping my To Dos in an electronic system for a while, but in the end I went back to the paper-based list which I kept on the desk in front of me – it was just more visible and more flexible to change and add to.

A key element of Davenport’s approach is to eliminate clutter and piles, and generally get paperwork under control. She recommends getting rid of 95% of old files as most will never be looked at again. My own experience concurs with this – though, as ever, there is always the conundrum of which 5% you are going to need later. Davenport’s answer is that you can get hold of most documents again if you really need them, and that this hindrance is minor compared to the benefits of being paper-light. For filing cabinets, the book recommends avoiding a straight A-Z system, and instead suggests allocating a major topic to each drawer, dividing each major topic into sub-categories, and finally filing chronologically inside the sub-categories with the latest at the front (the rationale for this is that if you look for something in a file the chances are it will be something you filed recently). Each file drawer should have at least two inches of play in it so when you want to file something, you can easily open the file with two fingers and drop in whatever you need to file. When drawers get too full, cull them to make an extra few inches space. I’d be interested in knowing how this approach works in today’s environment when most documents are electronic, and computer folders can expand almost indefinitely because so much storage is available on the modern PC or laptop. Is it worth doing a cull or do you just let the files accumulate indefinitely? I guess that, providing the file titles start with the date (in yyyy-mm-dd format) and include a short description, there’s really no downside. [in reply to this question, Liz Davenport said “I recommend occasionally culling entire folders and putting them in archive but, you’re right, with all that space, what the heck.”].

Unfortunately, however, there is a disconnect with email being in a different system. Most documents will come in by email so there is a question of whether to file them in the email system or take the trouble to detach them into the computer’s folder system. It would be interesting to know if Davenport has adapted her approach to deal with these contemporary circumstances [Her reply to this question was “I recommend a “Pending” folder in email. If there is something you need to take action on, write it down in your planner system first, of course, but then just drag the email to the pending folder so you don’t have to waste time searching for it. I also recommend a different code. Instead of the P with a circle around it for the paper pending, maybe a P with a square to denote the electronic pending.”]

Another mechanism advocated in the book to support day-to-day activities is trays (or, presumably, other containers such as folders or boxes) to contain the following collections of documents: a Desktop File for tasks you are currently working on or repetitive tasks performed daily, and to include a Pending File; an Inbox (to be emptied at least once a day); a To Read Tray (which should be purged when it gets full); a To File Tray (to be emptied when its full or when you go to the filing cabinet to look for something). Other trays can be added for particular specialist activities (such as ‘Things to go to Accounting’). Again it would be interesting to know what form Davenport recommends that these mechanisms should take in today’s environment [“Davenport’s response to this question was, “The stacking tray system is still important because we still have paper, unfortunately. With email, new mail is “IN” and needs to be gone through each day. Do not have an electronic “TO READ” because you will not look in it any more than you ever look in the paper version. As to “TO FILE” if an email needs to be go in a specific file, create an email folder for that project/client and move it to there.”]

A significant point made in the book is that you have one life so you should have one Air Traffic Control book for BOTH your business and your personal life. I certainly concur with this, and have done so ever since working with a prototype electronic diary in the 1980s (see ‘Towards the Electronic Pocket Diary’, Design Studies, Vol 5 No 2, pp 98-105, April 1984). This was a word-processed document on double sided A4 paper which was folded first in half and then in three, and carried around in a pocket in my wallet. It included line items for all my activities – work and domestic; a To Do list sandwiched between the previous few days activities and the upcoming activities stretching out as far as necessary; and a whole series of other information including names and addresses, facts & figures, books, records, papers to write, etc.. I found that this document had to contain everything relating to both my business and my home life to be viable and useful.

Interestingly, Davenport notes that it is useful to be able to store old copies of the Air Traffic Control book in order to have a clear record to supply to the tax authorities if they audit her. I absolutely agree that it is useful to have old copies – though my experience has been that I use them to find out what I was doing or to find out other information from that time. I maintained my wallet diary from 1981 to 1993 (when I started using a Psion organiser and subsequently the Lotus Notes calendar). Before that period I have some, but not all, of my old pocket diaries. Since 1993 I have no records at all. Therefore I know from bitter experience that my word-processed diaries from 1981 – 1993 are outstandingly complete and useful compared to the rest of the material I have – or don’t have.

The book as a whole certainly puts forward a comprehensive approach to managing ones activities – though I did wonder If those who use it while working full time jobs, do continue to use it in their retirement. I can imagine that they might do so because it’s a just a habit they get into. I wonder also if it becomes more of an unbreakable habit depending on whether they are using a paper Air Traffic Control book or an electronic one. [Liz Davenport’s reply to this question was “That depends on the complexity of your life, but I recommend continuing to use a system but perhaps go to a week at a glance version, if that is enough.” she also added “The Order From Chaos system is easily scalable to fit your life, whether working or retired.”].

There is certainly a question mark in my mind as to whether the whole approach still works in today’s environment of mobile phones and all-pervasive email; however, to the best of my knowledge, I don’t believe a revised and updated version of this specific book has been published (though Davenport did publish a shorter, 104 page e-book in 2011 called ‘Order From Chaos for Students’ which I haven’t read). There are however, a large number of hints and tips which are valid regardless of how digitised we become. I’ll end this review with some of the one’s I liked best:

- If you go along with unwanted interruptions you are encouraging bad behaviour in others.

- If you want to concentrate, eliminate all distractions. Lock your office door or go somewhere else.

- Do one task at a time. Make sure only the things you need for that task are on your desk. Work it until you complete it.

- Stations represent frequently repeated tasks requiring specific tools; a station includes ALL the tools needed to complete the task. A station can be a desk drawer or a box or a table top.

- Crumpled up paper takes up much more space in the trash can than flat uncrumpled paper does.

- Don’t bother shredding. It is time-consuming and if ‘they’ want to get you, they don’t need to go through your trash to do it.

- To persuade people to be organised, they must perceive that life is easier when you are organised than when you are disorganised.

- Don’t ask ‘how should I file this?’, but rather ‘how will I use it?’ For example, don’t file bills by the organisation concerned but by month. Even better just put paid bills in a box with the latest one on top.

- Tasks that will take longer than one hour should be scheduled as Appointments.

- Consider putting at least one thing on your list every day that is a step toward a larger longer-term goal.

- Achieve closure at the end of the day by always spending 5 minutes reviewing your Air Traffic Controller to see what you’ve achieved. Mark every item with either a tick for done, an arrow for rescheduled, and an X for no longer an issue. At the end of your 5 minute review, draw a big line across the whole of the day to give yourself closure and permission to stop thinking work.

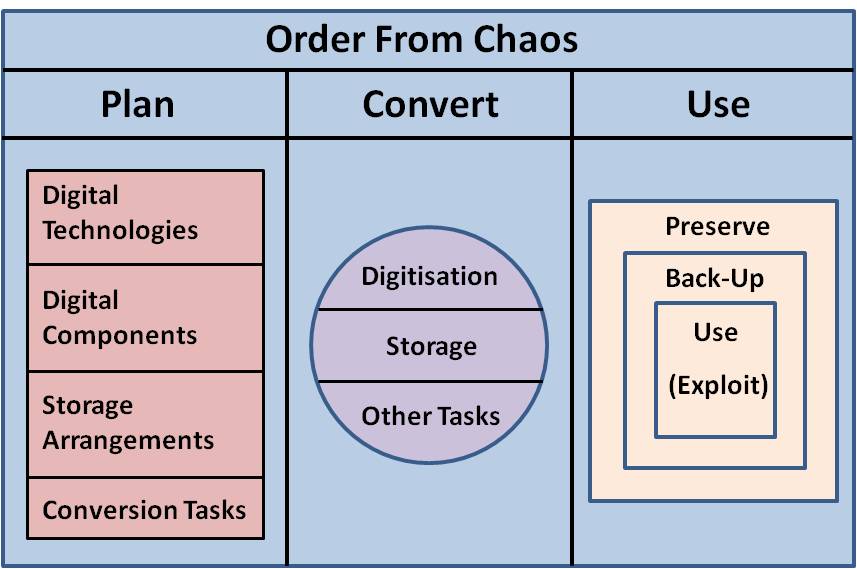

To test the usefulness of the model I’m going to apply it retrospectively to the OFC transformations I have reported on in this blog.

To test the usefulness of the model I’m going to apply it retrospectively to the OFC transformations I have reported on in this blog.