Backing Up has always been an essential part of maintaining my personal document collection; but it was never something I enjoyed – I did it out of a fear of loss. And I have, indeed, experienced loss: in 1996 one of the MO Disks I was using became corrupted and I lost a number of files; in 2004 my laptop was stolen and my whole document collection had to be re-instated from the backups; and in 2017 I had a system crash and, although the repair company was able to recover all my data in that instance, that might not always be the case.

When I was working, I used to take a backup of the more recently created material every month or so, as well as complete versions of the whole collection as it kept growing. This produced multiple copies on many disks which increased my confidence in being able to replace any file that got corrupted or mislaid, but which required managing in its own right as the number of disks grew. As time went by I added other backup mechanisms including storing a copy on another laptop in the househoId, storing a copy on disk in a relative’s house located many miles away, and storing a copy on disk at my son’s house in New Zealand.

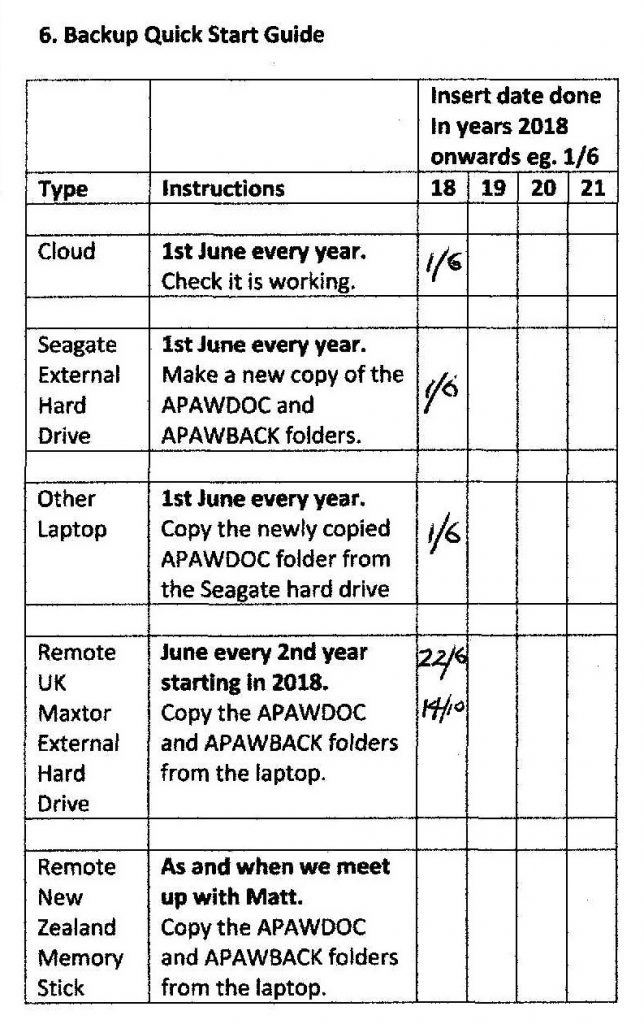

After I retired I tried to put the backing up on a more orderly basis and finally fixed on five different types of backup – Cloud, copy on another laptop in the house, local hard disk, remote (in the UK) hard disk, and New Zealand copy on memory stick. I scheduled backups in my iPad calendar for each of these (though, for the Cloud, it was more a matter of checking that it was working and that I could recover from it). However, the iPad calendar doesn’t have a To Do mechanism and I wasn’t looking at the calendar anything like as often as I used to at work. Consequently, I kept missing scheduled backup activities – and, in most cases, didn’t realise I’d missed them; and when I did realise I just kept putting off what was an annoying extra thing to do. One answer would have been to get a To Do app – but I’d had enough of To Dos at work.

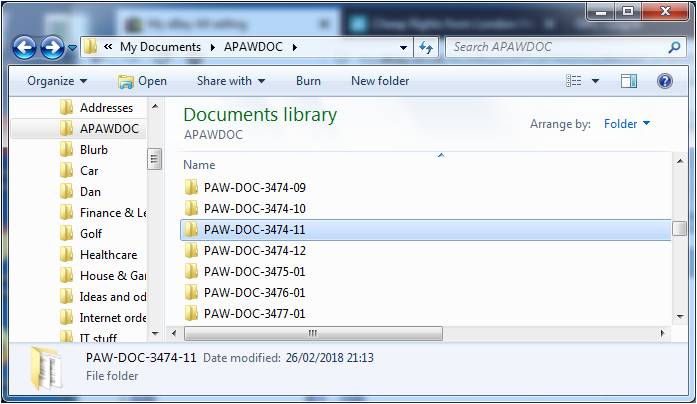

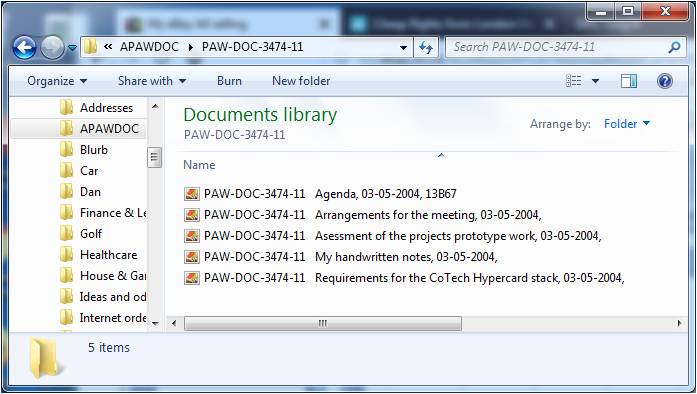

The opportunity to come up with an alternative approach, came when I created a Users’ Guide for my document collection in May 2018. I structured the Guide so that it had a Quick Reference Guide to the Collection on the front page, and a Backup Quick Start Guide on the back page. The latter listed the different types of backups to be performed and provided cells to be filled in with a date when that particular backup had been done, as shown below.

This was a definite improvement over dates dotted about a calendar, but unfortunately the schedule was still hidden because the Users’ Guide was tucked away inside an archive storage box.

This was a definite improvement over dates dotted about a calendar, but unfortunately the schedule was still hidden because the Users’ Guide was tucked away inside an archive storage box.

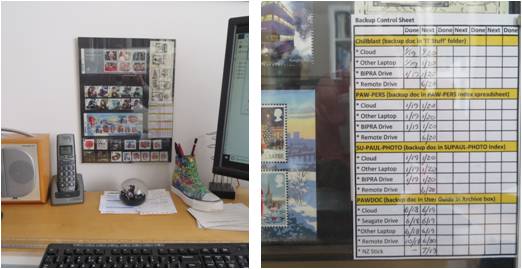

When I replaced my Windows 7 laptop for a Windows 10 version in December 2018, I decided to review all my backup arrangements again and to try to overcome this lack of visibility. The answer turned out to be really quite simple: I have a display frame for the latest issues of UK postage stamps, on the wall in front of where I sit at my desk. So, I created a table with columns for when backups have been done and when they are due; and this table now resides in the display fame as shown below.

I have a clear view of when the next backups are due every time I sit down at my desk. The next time I miss a backup it’ll be because I just don’t enjoy doing them, not because of blissful ignorance!

I have a clear view of when the next backups are due every time I sit down at my desk. The next time I miss a backup it’ll be because I just don’t enjoy doing them, not because of blissful ignorance!