Although digital technology provides many benefits, unfortunately there are some unavoidable overheads that go with it. One of these is the absolute need to backup digital files to avoid loss by system crash, virus infection, or theft. Backups can be done in a variety of ways including to external hard disk or to DVD or to a cloud service. However, the important thing is that they are done regularly so that all your material is backed up at any one time. Background facilities that do this automatically for you each time a new file is created, are the most reliable. For particularly precious files, it is best to have more than one backup and to keep one of the copies at some other geographical location away from your house.

Even with reliable backup arrangements in place, there is another longer term threat to your digital objects – out of date computer hardware and software. Computer technology is continuing to change rapidly, so just because you can access and use your digital objects today, doesn’t necessarily mean that you will be able to do so in twenty years time – especially if you have been using less well known application programmes. Generally speaking, if you keep updating your equipment every six or seven years, and if your files are in common formats such as Word, Excel, PDF and JPG, then you should be OK. However, even then you will need to be checking every few years that you can still access all your files, and to be converting those that are in danger of becoming unreadable to newer longer-lasting formats. For small scale digital collections, this is probably best done on an ad-hoc basis when you are considering purchasing your next computer system (though, if you want to take a more structured approach, you may find it useful to construct a maintenance plan. However, for organisations with large scale digital collections, this is a very serious problem and a field of study called Digital Preservation is now well established with many umbrella organisations and thousands of practitioners throughout the world. Some of the organisations issue guidance about file formats and these can be found by searching the net for ‘digital preservation file formats’.

The above discussion concerns digital objects; however, the general issues of protection and preservation can also apply to physical objects as well. For example, particular types of physical objects can be badly affected by sunlight and hot room temperatures so these factors have to be taken into account when choosing storage locations; and periodic checks should be made to ensure that the condition of the collection is not deteriorating. Theft too is another potential hazard, though this should be addressed by the household’s general security arrangements and insurance policies. The ultimate protection of storing things in bank vaults seems to defeat the point of having the collection in the first place.

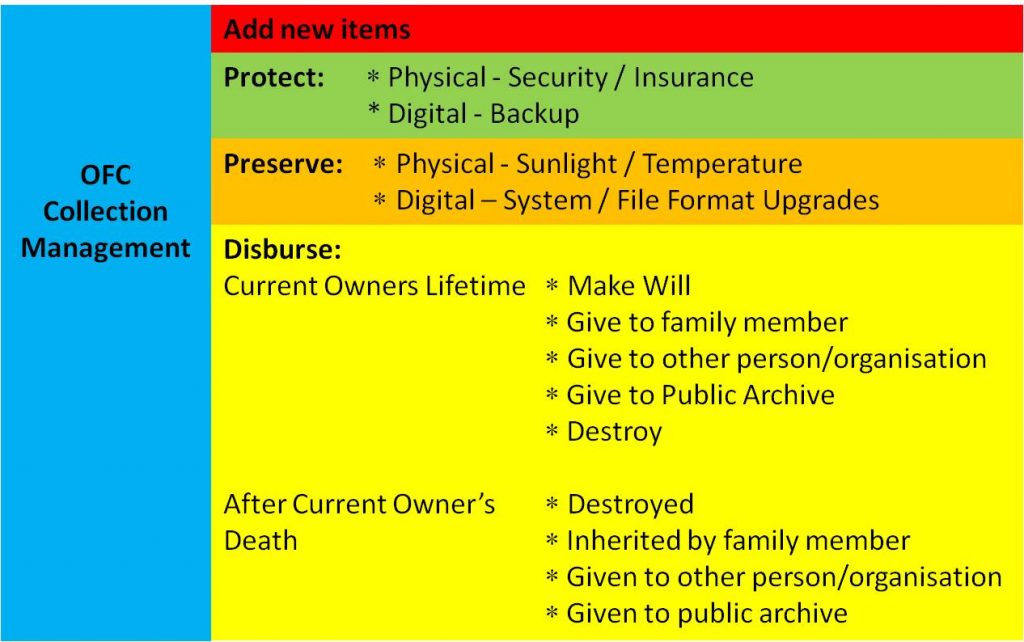

If a slightly broader perspective is taken, the overall maintenance – or management – of a collection will not only include all of the above, but also the activities of adding new material (as discussed in U5.6) and its eventual disbursement. Regarding the latter, owners have the option of either writing down what they wish to occur in a will, or of actually carrying out the disbursement themselves during their lifetime. All these activities are summarised in the diagram below.